And Then I Wrote

Two decades ago, I found my calling.

Do you know when and where you were when you found your calling? Amazingly, I do.

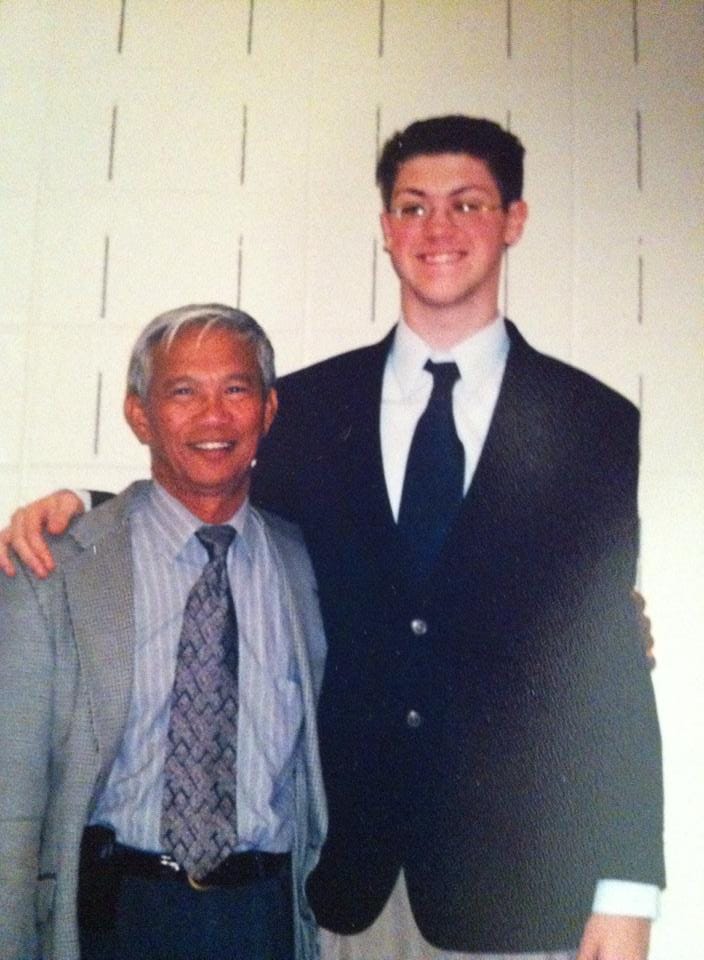

On May 25, 2005—20 years to the day that I am publishing this—I scored one of the biggest coups of my juvenile journalism career, interviewing Dith Pran, a New York Times photojournalist, activist and survivor of the Cambodian genocide. The story was a far cry from the sort of cultural, entertaining stuff I enjoyed pursuing even then, but it proved to me for the first time that, perhaps, I had a sense of how to find stories of public interest and share them, which is the most important thing about journalism, to me.

At the time, I was a senior at South Plainfield High School with a part-time job at The South Plainfield Observer, the borough's weekly newspaper. I earned CD money formatting copy and reporting on goings-on around the school and town, from high school sports to police and fire department chaplains. I had already enrolled to attend Seton Hall University in the fall, but I couldn't find it in myself to contract "senior-itis," which probably agitated me as much as it did my classmates, who were only too ready to move on with their lives.

My AP U.S. History class was taught by a woman named Fran Flannery, who possessed a keen interest in the subject. I believe she also helped coach the girls' field hockey team, and most interestingly, as the head of the history department, had implemented a bold elective of genocide studies. I want you to think about that for a second. In a time before Facebook or Twitter mainstreamed (and perhaps coarsened) discourse about such things, here was a teacher educating young minds not only on the Holocaust, but goings-on in places like Armenia—a genocide that the U.S. government would not recognize until 2019. I don't remember how much I had the capacity to admire it then, but I certainly do now.

Toward the year's end, Flannery was organizing a visit to the school from Dith speaking about his harrowing experiences in his homeland in the 1970s. As an assistant to New York Times writer Sydney Schanberg, Dith helped chronicle the takeover of Phnom Penh, Cambodia's capital, by the Khmer Rouge regime. Schanberg was able to leave the country as a foreign journalist, but could not get Dith out—and he suffered four years in labor camp conditions, hiding his "intellectual" past to survive. After escaping to Thailand in 1979, he was reunited with Schanberg and his own wife and children in America, shot various photos for the Times, was the subject of the Oscar-winning 1984 drama The Killing Fields (in which Haing S. Ngor, a doctor who also survived the Khmer Rouge's violence, portrayed Dith in an Oscar-winning debut performance), and campaigned tirelessly for justice in the name of the more than two million who died in the massacres. (Convictions would not occur until the 2010s, not long after Dith died of pancreatic cancer in 2008.)

Haing S. Ngor, who played Dith Pran, was shot and killed in 1996 in a baffling and tragic incident outside his home.

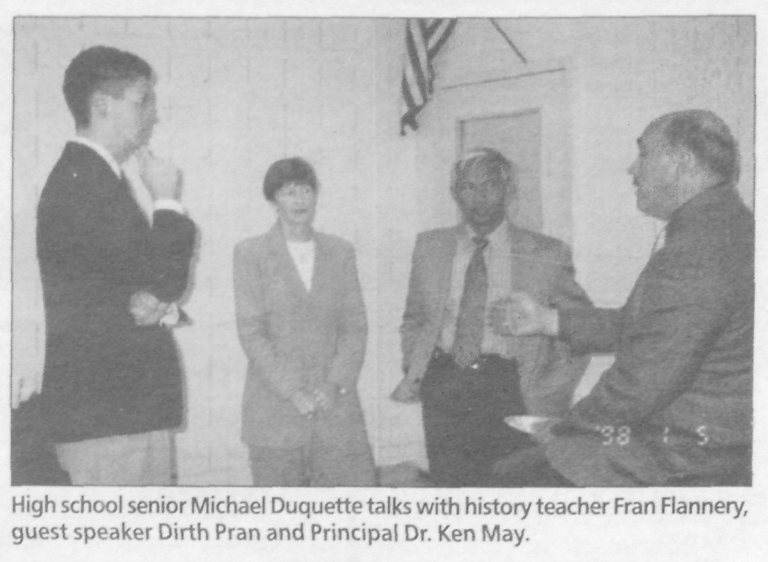

Perhaps others saw the assembly as a chance to skip some classes, but I thought it was a fascinating story. But what, I thought, would be my excuse to attend? Immediately I realized: I could write about it for the Observer. With Flannery's kind assistance, I not only saw Dith's speech but was granted some one-on-one time with him. I have some pictures of the event that I've not scanned, but one thing I do remember is a vaguely surreal candid: on one side of the table is me, reedlike in a brass-button blue blazer, holding a pen and notepad as I gesticulate mid-question; on the other side, Dith, in a grey jacket, listening intently while eating a big-ass deli sandwich that had been catered to him. (Schanberg's book The Death and Life of Dith Pran goes into detail about the adverse conditions Dith faced in the labor camps, subsisting on rats and vermin. Then and now, I think how quietly satisfying that sandwich may have been.)

My story on the event was published in the Observer on June 3, 2005. You can see the original paper here or read my transcript below. It's not up to me to say if it's "good" or even "important," but it was a majorly pivotal moment for me. It certainly proved my potential as a writer and molded me into someone trying to actively engage with social justice whenever possible. The one quote I always remember is the kicker: "Evil can never live forever." In a time where that doesn't always feel the case, it's nice to believe he's correct.

Survivor of Cambodian Genocide Visits SPHS

by Michael Duquette (South Plainfield Observer, June 3, 2005)

On May 25, students at South Plainfield High School had the privilege of meeting Dith Pran, a humanitarian and survivor of the Cambodian genocide of the 1970s. Dith spoke about the history of the notorious genocide committed under Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge regime, his amazing story of survival, which was recounted in the award-winning 1984 film The Killing Fields, and his feelings on peace and its place in the world today.

The genoice, Dith explained, was a consequence of the Communist influence of North Vientam on the neutral country of Cambodia. As the Vietnam War worsened, more Cambodians decided to adhere to Communist doctrines under the Khmer Rouge (meaning "Cambodian Reds")—but a vast majority of Cambodians, believing in the ideals of freedom and democracy, chose to side with the Americans during the war.

Then on April 17, 1975, disaster struck. The Khmer Rouge invaded the Cambodian capital of Phnom Penh and overthrew the government, proclaiming the "Year Zero" and beginning to exert forceful control over Cambodia. For four years, the Khmer Rouge sent Cambodians to serve the state in the infamous "killing fields," resulting in over two million casualties. Dith, an assistant to former New York Times correspondent Sydney H. Schanberg, was among those sent to work. Fortunately, Dith managed to escape to freedom in October 1979, crossing the border to Thailand and ultimately reuniting with his wife and children in America.

Since his harrowing journey, Dith has worked as a photojournalist for The New York Times since 1980, saw his story become an acclaimed film, received several honorary doctorates, compiled and published a book, Children of Cambodia's Killing Fields: Memoirs by Survivors (1997), and founded the Dith Pran Holocaust Awareness Project. The project, according to its official website (www.dithpran.org), is "to teach students about the Cambodian genocide/holocaust, its mass destruction and wholesale loss of life."

Dith, now 62 and living in Woodbridge, engaged students with his tale of survival and his utter humility with regards to his captors and his loss. When asked his feeligns on the Khmer Rouge, who still exist but no longer have power, he responded, "I feel that what they did is wrong, but I didn't think anyone should kill them. The past is the past; let's make the future better." He also stated his advice for survival: "When you are indentured you have to look around and find a way to survive. Go with the flow—that's the way to survive." These are no small words from a man who ate whatever he could find while serving the cruel regime—he totld students that what animals eat without harm are obviously edible for all life.

Dith also commented on the possiblities of peace today, even with world affairs depicting a world in which injustice is stronger than ever. "The world is getting more sensitive," Dith stated, "[there is] more talk, more support, more sense of doing something." He encourages the support of movements for peace and justice, notably commenting on the possiblity of bringing the perpetrators of the Cambodian genocide to justice—minus Pol Pot, who died in 1998.

In spite of his survival and accomplishments to aid world peace, Dith Pran refuses to consider himself a hero; rather, he considers himself just an observer of history with a story to tell. He admits, "I cannot understand why I survived," but does not dwell upon the intervention of fate and instead continues to lecture and promote his message. During his time at South Plainfield High School, he proclaimed his biggest motive behind his crusade, which ahve certainly become a new philosophy to all who had the pleasure of meeting the great Dith Pran: "I never give up, and I believe that evil can never live forever."