Dear John

A new documentary on the legendary film composer is insightful, even as it leaves you wanting more.

At one point in Music by John Williams, the new Disney+ documentary on the most celebrated living film composer, writer/director J.J. Abrams attempts to contextualize the power of Williams' body of work. Abrams, who worked with The Maestro on two Star Wars sequels in 2015 and 2019, compares him to The Beatles - each musical icons who would earn a place in the cultural firmament through any of their best-known works, let alone all of them.

With such an expansive body of work - a total of five Oscars (among 54 nominations, five behind Walt Disney's record), three Emmys, four Golden Globes, 26 Grammy Awards, the Kennedy Center Honors, the National Medal of Arts, an American Film Institute Life Achievement Award (the first for a musician) and a place in the Songwriters Hall of Fame - it is difficult to imagine how a 106-minute documentary could paint an accurate portrayal of the living legend. Music by John Williams gets as close as one film possibly can. It's an essential primer on Williams for casual aficionados that offers a few tasty side dishes for converted fans. It would have been closer to perfect if it was up to an hour longer, and up to 20% less adulatory.

Music by John Williams, a joint venture of several of the film companies who have benefitted most from the composer's work (Steven Spielberg's Amblin Entertainment; the George Lucas-founded, Disney-owned Lucasfilm; Ron Howard's Imagine Entertainment), is directed by Laurent Bouzereau, a noted documentarian who's helmed informative documentary bonus features for many of Spielberg's laserdiscs and DVDs. Recently, he's pivoted to retrospective documentaries on old Hollywood icons like Natalie Wood and Faye Dunaway. His last effort for Disney+ was Timeless Heroes: Indiana Jones and Harrison Ford, an advertorial for last year's finale to the adventure series Spielberg and Lucas created in 1981. In a lesser world, Music by John Williams would more closely match the tenor of that feature, and indeed, most documentaries on storied creatives. Essentially, they're commercials: feature-length arguments for Rock and Roll Hall of Fame canonization or catalog retrospectives to draw eyeballs to the latest (and often least) installment in a deathless franchise.

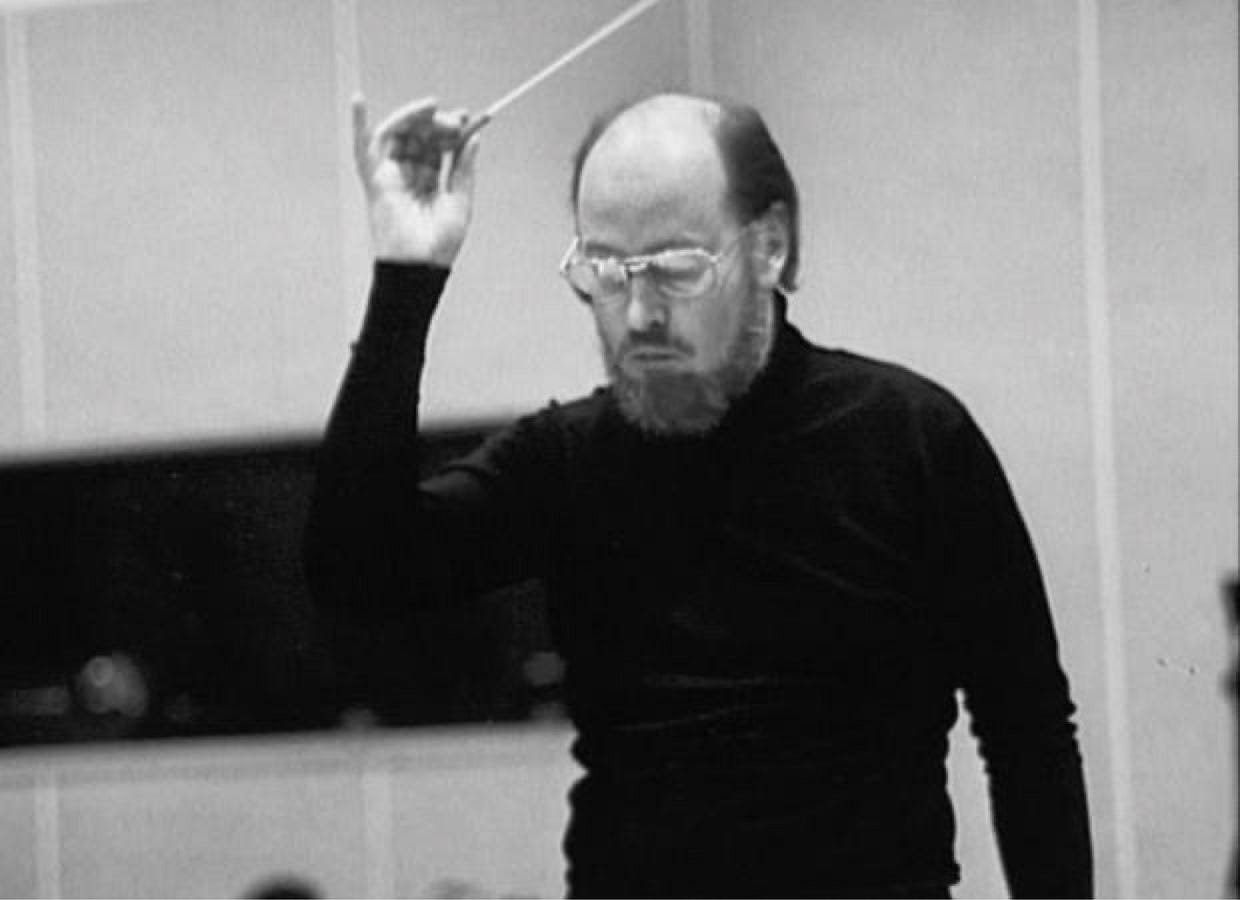

At 92, Williams has little to prove. Since the turn of the millennium, his film works can be put into buckets marked "Star Wars" (both prequel and sequel trilogies, occasionally so disjointed that even his scores got lost in the shuffle by the end) or "Spielberg" (the director and composer have done all but five films together - if they collaborate on Spielberg's rumored 2026 sci-fi film, it'll be their 30th). The exceptions are few: three Harry Potter scores solidified his reputation as a master of celluloid fantasy, and three dramas - The Patriot (2000), Memoirs of a Geisha (2005) and The Book Thief (2013) - offered stateliness if not major innovation. But he's hardly rested on his laurels. Though he graduated to conductor emeritus of the Boston Pops after a 14-year tenure between 1980 and 1994, he continues to lead orchestras in concerts across the U.S. and Europe, even supplying them and players like violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter and cellist Yo-Yo Ma with original concertos and rearranged film themes to perform, free of flickering images and recast as "serious" concert fare. His relative public absence this year - cancelling all his engagements due to an undisclosed ailment but vowing through statements to make a full recovery - are a shocking glimpse into a world without his gifts at close hand.

And what gifts are shown in Music by John Williams! Space is given for the usual suspects of Williams' discography - Star Wars; Spielberg films like JAWS, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial, Jurassic Park and Schindler's List; the Harry Potter triplicate; still-utilized fanfares for the Olympics and NBC News - but they are often told with details that careful observers may not have recognized. Spielberg's self-shot footage of nearly all of Williams' recording sessions for his films are a mainstay of Bouzereau's docs, but here, pieces are allowed to linger like never before: a brief snippet where Williams mulls a scene from JAWS from which he will later remove a musical cue, or session pianist Ralph Grierson rehearsing the dazzling piano figure that begins E.T.'s end credits. When Williams retrieves his leather-bound paperwork for Close Encounters and the camera briefly lingers on staves of other potential five-note figures, it's like seeing an early sketch of the Sistine Chapel. Some familiar chestnuts are reprised - Williams loves to share Spielberg's quip about scoring Schindler's List - but many are not. (I figured the film would include known stories of Williams writing two themes for Indiana Jones that were both used, or how Spielberg re-edited the finale of E.T. to better match Williams' and the orchestra's performance.)

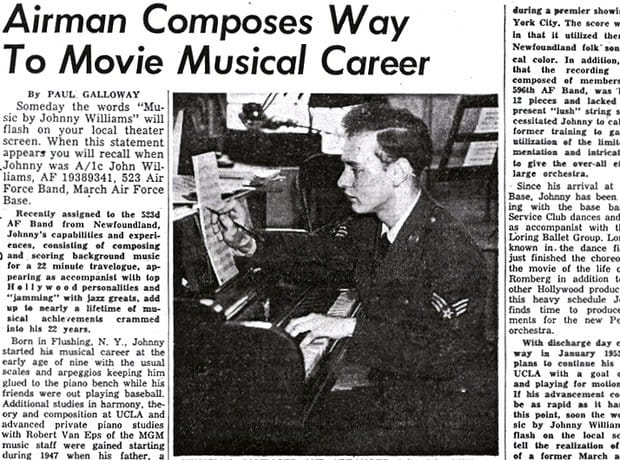

The film's first half-hour is a holy grail for Williams devotees, featuring candid reminiscences from the composer of his childhood, parented by a jazz drummer father and a dancer mother. ("My parents' friends were all musicians," he says in one interview. "That's what I thought you did when you were an adult.") This section traces his journey from trombone-loving jazzbo to rigorous pianist to nascent orchestrator during a four-year stint in the Air Force - curiously, his post-service study at Juilliard isn't mentioned once - and hearing Williams recall his work on You Are Welcome, a short subject for the tourist offices of Newfoundland that became his first composer credit, is a breath of fresh air from the typical Williams biography. As the section skates through early film and television credits (back when he was known as "Johnny Williams") and session piano work on scores for Henry Mancini and Elmer Bernstein, you beg for the brakes to be pumped so you can marinate in this section more.

And then the narrative does slow down for an early, heartrending detail of Williams' life that is rarely mentioned, least of all by him. In 1974, actress Barbara Ruick - Williams' wife of nearly two decades and the mother of his three children - died of an aneurysm while filming a Robert Altman picture. To this point, he's recalled by his daughter Jenny - the only of his children to sit for an interview - as a caring but workaholic father who cedes parental oversight of her brothers (including Toto singer Joseph and session drummer Mark) to her. It's a bittersweet point that perhaps can only be lingered on so much, along with the notion that this personal trial preceded his ascent to an unprecedented level of commercial success for a film composer, with JAWS, Star Wars, Close Encounters and Superman all following in the four years after Ruick's death.

There are a couple moments like this that offer the documentary's greatest frustrations - trenchant points about Williams' work and its place in culture that are probed just beneath skin-deep before ceding the floor to a mix of intriguing and occasionally bizarre talking heads. For every trenchant observation by composers David and Thomas Newman (two sons and two nephews of veteran 20th Century-Fox composers Alfred and Lionel, both major mentors of Williams') or even, hand to God, Seth McFarlane, on Williams' composition style or his at-times awkward place in the classical music conversation, you get a few too many bubbly mash notes by Coldplay frontman Chris Martin or J.J. Abrams, whose reaction to Williams' deference to a project's director is miles away from Star Wars creator Lucas, who praises his friend while still asserting his own vision.

The ever-humble Williams is not always the best self-assessor, either: while he approaches moments like his temporary resignation from the Boston Pops in 1984 with refreshing candor, a bit too much hay is made over the perception of the composer as a lone Luddite drafting themes at a piano with paper and pencil, while Hollywood shifts to a slicker mode of scoring. While Williams' big-picture declarations of the present moment in film scoring as "a time for questions" is certainly interesting, he frames it as part of our culture's musical development, when the Zimmerfication of scores probably has more to do with what audiences want (or think they want) and where studios are willing to cut corners. It also creates a sort of intellectual paradox: if audiences by the millions are aware of his work, streaming his albums and attending his conducting engagements, why have so few composers cast themselves in his image today?

Even an incisive documentary might be the wrong medium for such conversations. (Luckily, the right medium might be on its way: a biography of Williams is coming from Oxford University Press next year.) What Music by John Williams does - and does well - is show what makes this living legend tick, and how that ticking inspires us to hear film differently, or to tap into a musical tradition that's even older than this film's subject.

The film ends with a typically thoughtful and profound observation from a man whose staggering body of work continues to fuel our souls daily: "Music is enough for a lifetime, but a lifetime is not enough for music." If there was one person I wish the latter was true for, it would be Maestro Williams. He's earned it - and Music by John Williams is the imperfect proof.