Gregg Alexander Cannot Die

He's got the music in him.

In no sense am I some sort of pop chart wizard or ardent trend watcher. When Sophie Ellis-Bextor's "Murder on the Dancefloor," a U.K. No. 2 hit from 2002, garnered an unlikely boost late last year for being used in the divisive film Saltburn, I paid it no mind. It wasn't until my pal Alex Mercuri, a great guitarist in the group Pom Pom Squad, posted his ongoing appreciation for the song that I gave it any real thought. Boy, am I glad I did.

Hey hey hey hey.

"Murder on the Dancefloor" is a great pop single. Goes down easy and fun, like they should. Holds up on repeat listens. You know the drill. But what is it about the track that sets the Duque-signal alight? That would be in one name: the song's co-writer and co-producer, Gregg Alexander.

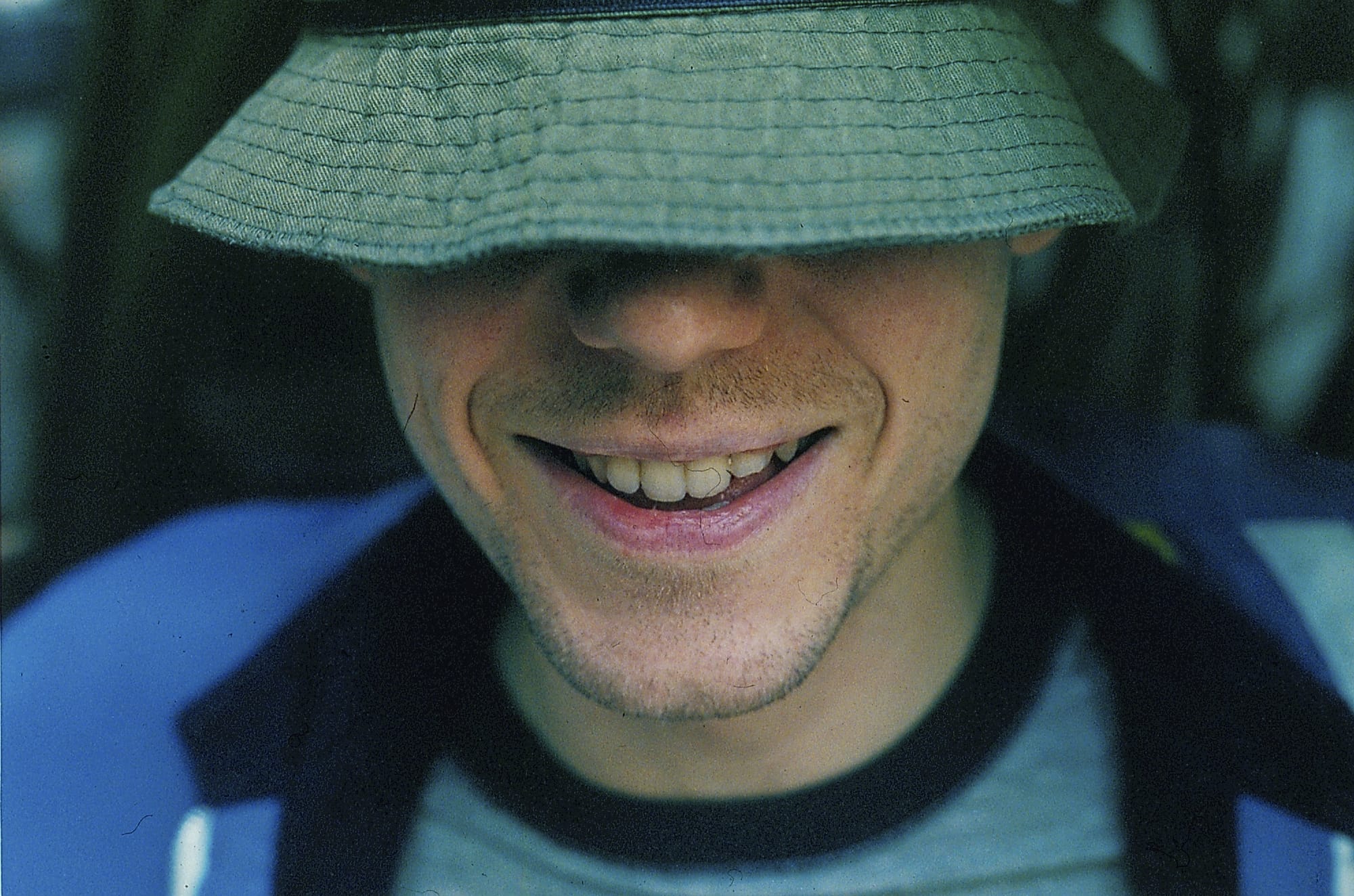

That name may mean nothing to you, but if you're a freak for liner notes (that is what I am) or simply effortless pop songs like these, Alexander's name is a beacon, a titan among craftsmen of song. In 1998, Alexander had his own brush with success as the frontman (and ostensibly main guy, although we'll get into that) of the alt-pop collective New Radicals, whose lead single "You Get What You Give" was a breath of fresh air that did its best to reset culture for the century ahead. A U2-ish paean to dreamers that spit in the face of the consumerism and capitalism that helped propel it to the U.S. Top 40 - and reportedly saved Joni Mitchell from quitting music - "You Get What You Give" made Alexander a virtual immortal. It also helped him vanish. New Radicals were quickly done after releasing the album Maybe You've Been Brainwashed Too, and that was the last time most people considered the squirrelly man in the bucket hat.

So many odd bits elevate "You Get What You Give" to classic status: the Michael Jackson "aaow"s, the whispered "flyyyyy," that one chonka-chonka-chonka drum fill, the guitar tones that predated All That You Can't Leave Behind by two years. I could go on!

But Alexander never really went away. He existed on the fringes of rock before New Radicals - releasing two albums under his own name and helping mastermind another by a friend and longtime collaborator - and continues to emerge every few years with an irresistible radio hit or unexpected mini-pop masterpiece. "You Get What You Give" was improbably canonized into the American firmament when Alexander donned that bucket hat one more time to perform as New Radicals during the inauguration of Joe Biden. (Biden has cited "You Get What You Give" as an inspiring song to cope with the loss of his son Beau to cancer.)

What is it about Gregg Alexander that espouses such high praise? For me, at least, it's the continuum he works on that values hooks, melodies and catchiness, but isn't afraid to wrap them in unusual suits of armor: the verbal acidity that closes "You Get What You Give," the woozy rhythms when Michelle Branch sings "a little bit of this / a little bit of that" or Adam Levine croons "youth is wasted on the young / it's hunting season and the lambs are on the run." He believes in the potential of pop music and could knock out easy wins in his sleep, but possesses an artist's soul and a wish to challenge himself every time his metaphorical paintbrush hits the canvas.

Off the strength of the "Murder" resurgence, Alexander has dutifully re-emerged to share his original demo and first interview in a decade with The Guardian ("Murder" was this close to supplanting "You Get What You Give" as New Radicals' lead single). As I hope he makes good on his evergreen promise to lift the lid on his songwriting treasure chest once more, here's a quick primer on what else he's done for anyone whose interest has been piqued by the thrill of "Murder" or the inevitable nostalgia/where-is-he-now bent of that deathless New Radicals hit.

Gregg Alexander's solo LPs were so negligibly promoted - but how do you even promote something that sounds like this?

Gregg Alexander, "The World We Love So Much" (1989)

Gregg Alexander was born Gregory Aiuto in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, living an ordinary existence in a strict Jehovah's Witness family until he discovered Prince's Purple Rain - ironic, considering Prince's future conversion to the same faith - and began singularly pursuing a music career. A combination of preternatural talent and dumb luck (t'was ever thus, in this business) landed his teenage demo tapes with Rick Nowels, an upstart writer-producer who'd made his mark working with Stevie Nicks and particularly Belinda Carlisle, whose terrific Heaven on Earth (1987) was produced by him (and featured the smash "Heaven is a Place on Earth," which he co-wrote).

Nowels has continued to work with Alexander all through his career - that's him playing piano on "You Get What You Give," which he co-wrote - but his first collaborations with the wunderkind as he embarked on a solo career failed twice. A&M released Michigan Rain in 1989 to crickets, and 1992's Intoxifornication, issued by Epic and featuring many of the same songs as its predecessor, fared similarly. One of the more undeniable gems, the hushed "The World We Love So Much," closed both albums, and found an admirer in another eccentric white boy of alt-pop, who cut his own version as a demo just before breaking out with his own meticulously crafted songs.

Danielle Brisebois' albums simply deserve a second look! Criminally underrated.

Danielle Brisebois, "What If God Fell from the Sky" (1994)

Gregg's next attempt at pop/rock inroads was an unusual side-fake, producing the debut album by a friend and fellow musician named Danielle Brisebois. Marketed as a new artist in 1994, she already had a considerable career as a child actor: in 1977, she originated the role of Molly in the Broadway musical Annie (that's her vocal sampled on Jay Z's "Ghetto Anthem (Hard Knock Life)") and later picked up a Golden Globe nom as the chipper niece of America's favorite bigot on the All in the Family spin-off Archie Bunker's Place. Brisebois was a talented songwriter in her own right - perhaps her best song, "Just Missed the Train," was co-written not with Alexander but one of the guys who wrote "Torn" - and her debut album Arrive All Over You was a chance for her and Alexander to explore the studio space and essentially invent the New Radicals sound.

Indeed, Brisebois is the other piece of the New Radicals nucleus, and many of their collaborators were heard on Arrive All Over You, including guitarist Rusty Anderson and bassist John Pierce. The album's opening track, heard above, posits a universe with a gender-swapped New Radicals, asking big-tent questions about faith, morality and society with no-nonsense hooks. Brisebois has been a consistent cowriter with Alexander ever since; the pair recorded another album under her name a year after New Radicals, Portable Life, that didn't get released until eight years later, with zero fanfare. (Brisebois, but not Alexander, also co-wrote the massive "Unwritten" for Natasha Bedingfield.)

U.K. pop watchers are on some whole other shit than here. Not a bad thing, as is the case here!

Ronan Keating, "Life is a Rollercoaster" (2000)

Like power-pop Infinity Stones, whatever songs might have been intended for the New Radicals stash - as B-sides or shards of a second album that never was - eventually got scattered to the corners of the globe. One of the first acts to catch them (and a lot of them!) was Ronan Keating, the genial frontman for Boyzone, an Irish boy band that recorded a boatload of hits in Europe. The playful "Life is a Rollercoaster," a perfect piece of faux-Motown for soulful white boys who love "na na na"s, became Keating's second career No. 1 single in England. Debut album Ronan (2000) found a few songs by Alexander and Nowels rubbing elbows with writing or production work by Patrick Leonard (Madonna), Stephen J. Lipson (Annie Lennox), Bryan Adams (Bryan Adams) and Diane Warren (loser of 15 Oscars) - and when follow-up Destination was issued in 2002, the pair ran the table - and Keating has rarely missed an album without a collaboration with Alexander.

As far as Rod doing a stalwart songwriter's castoffs, this is probably overall better than "Faith of the Heart," the Diane Warren-penned cheese he sung for Patch Adams, a different recording of which was the theme to Star Trek: Enterprise.

Rod Stewart, "I Can't Deny It" (2001)

He may be a great, unpredictable songwriter, but Gregg Alexander is also good enough to write to form from time to time. Case in point: one of his most workmanlike songwriting credits, "I Can't Deny It," which sounds like "You Get What You Give" with faster-paced, happy-love lyrics. This became a minor U.K. Top 40 hit for Rod Stewart, who would soon enough abandon pop for a decade with blockbuster albums of tunes from the Great American Songbook. Maybe having a New Radical in your corner was as good as it got.

To be quite honest, I like Santana and Branch's second collab, "Feeling You," written by hired guns Kara DioGuardi and John Shanks. They're no Gregg Alexander, though.

Santana feat. Michelle Branch, "The Game of Love" (2002)

Genre was nothing to Gregg Alexander. Under the pseudonym Alex Ander, he spent a good portion trying his hand at partaking in the turn-of-the-millennium Latin explosion, penning most of the songs on Enrique Iglesias' 2003 album 7. (None of its songs were issued as singles, and none of those singles were hits.) The Ander pseudonym finally hit pay dirt with a slightly different sort of Latin pop affair: the shuffling "The Game of Love," co-written with Nowels, was a big hit for Santana in his superstar duet era that kicked off with the Grammy-winning Supernatural in 1999. (His vocal foil this time was Michelle Branch, the third choice after Tina Turner - whose version was issued in 2007 - and Macy Gray's takes weren't used.) At No. 5 on the Hot 100, it's actually Alexander's biggest pop hit, as well as a Grammy winner for Best Pop Collaboration with Vocals.

Daryl Hall is a genius. To some, he seems like an asshole. I don't think that, but maybe there's less distance between those poles than you'd like to admit.

Daryl Hall & John Oates, "Someday We'll Know" (2003)

"You Get What You Give" might have been the signature New Radicals song, but "Someday We'll Know" - a contemplative ballad issued as the album's second single, concurrently with Alexander's announcement to terminate the project - kind of became the group's standard. In 2002, Mandy Moore covered it on the soundtrack to the teen weepie A Walk to Remember (which featured another New Radicals track, the album opener "Mother We Just Can't Get Enough"), and Ronan Keating from a few blurbs above made it a staple of his live shows around the same time. My favorite version, however, might be a game-recognizes-game cover of sorts by a group who never missed a good pop trick, duetting with another great bedsit studio tinkerer - the one and only Todd Rundgren.

I can't prove this, but I imagine Gregg Alexander might have heard Maroon 5 at some point and wished he had Levine's plastic soul voice.

Adam Levine, "Lost Stars" (2013)

After the "Someday We'll Know" revival, Gregg Alexander's proliferation slowed to occasional appearances for heads, co-writing a song with Hanson and reaping the bonuses of the occasional, presumed New Radicals cast-off (one such tune was recorded by a reunited Boyzone in 2010). Only in the 2010s did he put pen to paper for a new, high-profile project: the soundtrack to the underrated indie Begin Again, written and directed by John Carney of Once fame.

The story of an idealistic record exec (Mark Ruffalo) and a struggling songwriter (Keira Knightley) learning to find their faith in art again was particularly fertile ground for Alexander - working again with Brisebois! - and his masterstroke was "Lost Stars," a ballad Knightley's character wrote for an onscreen ex-boyfriend who issued a grotesquely commercial version before playing it as intended. (Maroon 5 himbo Adam Levine played the boyfriend, an incredibly on-the-nose casting note. God bless him, that ballad version of his is the last good thing anyone in that band ever did.) Alexander's canonization as a legend in repose was solidified when "Lost Stars" took an Oscar nomination for Best Original Song - a fitting laurel for a man who's never cured his dreamer's disease.