Hollywood & Spine Archive: Let's Hear It for the Book

An overview of the novelization to FOOTLOOSE, originally published in February 2020.

This is yet another Hollywood & Spine you'll see on Duque's Delight that reflects my fascination with turning musicals or music-based movies into books. It's a special kind of weird! Also, this was a fun exercise in realizing the Footloose script was at the New York Public Library, and that I was able to compare it to both the finished film and the novelization. It was a really great idea I would have pursued in future installments had the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown not begun less than one month later. (Originally published 2/25/2020)

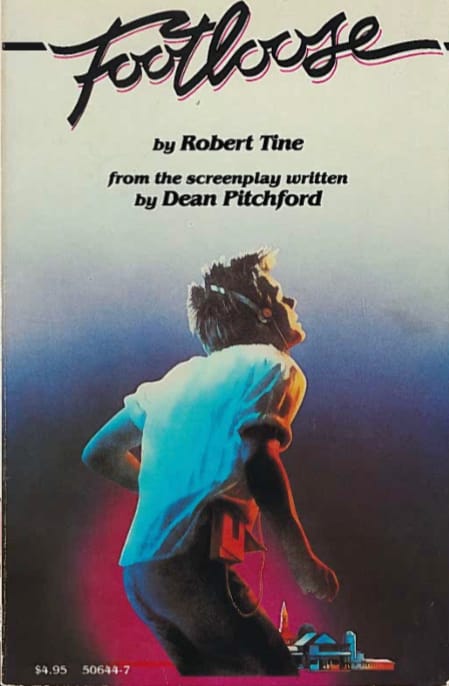

Footloose by Robert Tine (based on the screenplay by Dean Pitchford) (Pocket Books, 1984)

The pitch: A big city teen moves to a rural small town and shakes things up by challenging a local ban on dancing, launching the careers of Kevin Bacon and Sarah Jessica Parker in the process.

The author: Robert S. Tine (1954-2019) was equally known for the Outrider series of post-apocalypic sci-fi pulp novels (published as Richard Harding) and a slew of novelizations through the '80s and '90s. Footloose was his first, with Basic Instinct, The Bodyguard and Beethoven among his adaptations to come.

The lowdown: Footloose is well-known for capturing not only the early aesthetic of MTV on film but also telling a story that just resonates with teens of all generations. (As a cast member of the South Plainfield Summer Drama Workshop's 2002 production of the stage musical version, I can uniquely attest to this.) Rebelling against the rules on celluloid has been in fashion since Blackboard Jungle; the styles change but the message doesn't.

Of course, the delivery of the message certainly changes when turning a film like Footloose into a novel. Scriptwriter Dean Pitchford made a name for himself in the '80s as a songwriter: with Tom Snow, he won an Oscar and a Golden Globe for co-writing the theme to another teen musical film, Fame. The duo would then write hits for Melissa Manchester and Kenny Loggins & Steve Perry. Footloose, loosely based on a real occurrence in Elmore City, Oklahoma that fascinated Pitchford, naturally lent itself to songs, and Dean co-wrote of every one of them as featured in the movie.

Now, despite songs and script coming from the same source, Footloose was not calculated as a musical. The final edit fits the songs like a glove, but Pitchford confirmed in a DVD commentary that only Kenny Loggins' chart-topping "Footloose" and Karla Bonoff's "Somebody's Eyes" were in any stage of completion before production, and served as temp tracks for sequences like when Kevin Bacon's Chicago-raised hero Ren McCormick teaches his rural pal Willard Hewitt (the late, great Chris Penn) how to dance. A copy of the screenplay, dated March 16, 1983 and in the collection of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, doesn't mention a single song, either. (The script does, however, omit an ill-advised rap sequence that was shot but unused - watch Bacon when he leads the kids in planning the film's final dance, he's delivering some sort of lyric.)

So Footloose the book has to get the drama across while describing things that the reader cannot see or hear. We've covered similar novelizations like The Rose, but the songs of Footloose are so ubiquitous - can it work on the page? Luckily, the answer is mostly yes. The characters certainly don't depend on the songs to work. Sometimes the cultural references are vague (at one point, Ren and Willard - named Bryan here and in the script - pick from tapes by Kenny Loggins, The Police and The Clash, giving him more of a punk and new wave edge than what fully transpires on screen), and sometimes they're entirely off-base (Ren's mother compares his first-day-of-school skinny-tie outfit to Willie Nelson instead of David Bowie). But Pitchford clearly did his homework on teen rebellion films, and Tine's prose reflects that.

Tine also knows how to build the drama in a way the final film could sometimes subdue, primarily the conservative terror of Bomont's adult population that even gives the town's preacher (and the story's primary adversary), Shaw Moore, considerable pause. While he's a staunch enforcer of the laws against dancing, the novelization shows that he's not nearly the most villainous adult in town. Among those threats: local couple Roger and Eleanor Dunbar, seen toward the end of the film burning books and accusing Moore throughout the book as being less dedicated to the moral crusade than they are. There's also a greater presence of Burlington Cranston, the town's fire chief and the father to teen antagonist Chuck (who Moore's daughter Ariel dates until she falls for Ren's rebellious charms) - but more on that in a bit.

The novelization answers two questions that its source material doesn't feel obligated to explain: Bomont's geographical location and the status of Ren's father (which, it's implied, spurs Ren and his mother's move to Bomont in the first place). Pitchford has stated that the mystery of Bomont was intentional: it's clearly Texas in the musical and Georgia in the 2011 remake. While it's indeed never mentioned in the script, Tine places it definitively in Oklahoma, where the picture was filmed. As for Ren's absent father, even the script can't get it right: an early description of Ren's mom describes her as a widow, though Ren suggests in both the script and the film that his crusade to challenge the dancing law may have had something to do with his dad leaving them. In the book, his passing is made clear, having drank himself to death after losing his job, found by his horrified son. When you take away its sugary pop songs, there really is a lot of drama in Footloose.

The cutting room floor: There are a few scenes in Footloose's script that make for interesting color in the novel. The odious Chuck Cranston, it turns out, is connecting Bomont's low-level drug dealers with product, so when Ren flushes a joint he's given in an attempted sting (and confronts Chuck about it, leading the bully to unwittingly crash his car into a cop's vehicle), it more directly sets up the duo's eventual chicken race on tractors.

The Cranston family figures heavily into a deleted scene and subplot that's actually shown in the novel's black and white photo spread: while traveling back from a bar to dance with his friends, Ren finds his boss, mill owner Andy Beamis', field on fire - but when he goes to the home of Burlington Cranston, the fire chief declines to help. It turns out that the Cranston family thought Beamis' land should be theirs, and vengefully pushed to get part of the property rezoned to neighboring town Bayson. (Of course, this works in Ren's favor by the story's end, when he throws a school dance at Andy's mill and out of city limits.)

Finally, there's a notable omission involving Shaw Moore's silent but powerful wife Vi. Late in the story, when the dance debate is at its height, she visits the local hairdresser, her best friend from high school and a polar opposite to the conservative Vi. The rapport they have in private - Vi dares to drink a beer and imagines seeing an ocean for the first time - anticipates her eventual pushback against Shaw's moral crusade, and is a welcome moment of character development.

The last word: put on the soundtrack as you read and you're guaranteed an '80s Teen Reading Experience as good as Footloose allows.

Paid subscribers to Duque's Delight receive Hollywood & Spine. Tell your friends!