Hollywood & Spine Archive: An Introduction

The original introduction to Hollywood & Spine, published December 2018.

This is the first Hollywood & Spine I ever sent - a pretty clear-headed summary of what makes the practice of turning a movie into a book (instead of the other way around) interesting enough for me to write about it roughly once a month. I hope as we go through these archives together, you'll agree that points were made. I did one minor edit to the third-to-last paragraph, which ended with the appositive phrase "a rought." I have no idea what I was trying to say there. (originally published 12/4/2018)

Since films have been made, filmmakers have adapted literature for the screen. In 1899, Georges Méliès adapted both the Brothers Grimm fairy tale Cinderella and William Shakespeare's King John. Even his best-known original, 1902's Le Voyage dans le Lune, was loosely based on (or at least inspired by) works from H.G. Wells and Jules Verne. This inevitably led to the earliest debates about whether the book was better than the movie; as neither Wells nor Verne featured a space capsule going directly into a perturbed moon's eye, the advantage is Méliès'.

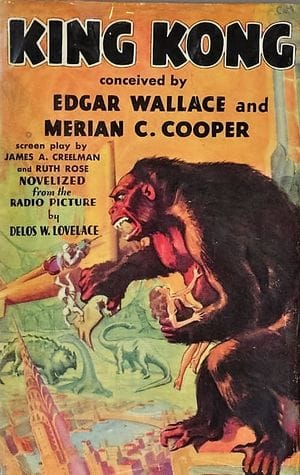

In the silent age, the motion picture business realized the advantages of swinging that door both ways, and publishers began to turn movies into books. Les Vampires, a silent French serial released in 10 installments through 1915 and 1916, was duly adapted in seven volumes of prose - one of the first movie novelizations. Soon, the concept had elevated: nearly six months ahead of its release in early 1933, author Delos W. Lovelace turned forthcoming monster epic King Kong into a book, to grasp the public's fascination before the giant ape even appeared on screen.

What drives us to something as quaint as novelizations? To me, their appeal is rooted in a pre-"infinite content" approach to film: before you could rent, buy or stream your favorite movies, and if you weren't lucky to catch a re-release, you could count on an inexpensive, mass-market book to relive the experience. At the same time, the novelization is a fascinatingly imperfect recreation: given the breakneck pace of publishing against Hollywood's deadlines, these adaptations often feature dialogue, scenes and even plot points that had little to do what you actually saw in the theater. Before the advent of DVD special features, these discoveries were minor monuments - a way to stoke the imagination without fully knowing if the curtain was being lifted behind the scenes or not.

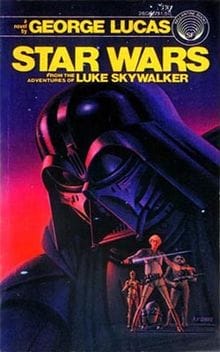

And consider the films most likely to turn into books, too. While dialogue-heavy dramas from Philadelphia to The Nice Guys sometimes get novelized, it's fantasy, sci-fi and horror that most often gets the literary treatment - stories that often need special effects and creative visual ingenuity to come to life in the first place. Readers with the foresight to pick up Star Wars: From The Adventures of Luke Skywalker in paperback in late 1976 went a full six months with their own personal vision of a galaxy far, far away; conversely, Craig Shaw Gardiner's 1989 novelization of Batman was a rare portrayal of The Dark Knight without any art. How does that work? Does that work?

It's these questions I plan to answer in Hollywood & Spine. Here, I will revisit dozens of novelizations to some of the best-known blockbusters and cult classics, assessing their success at adapting (or deviating from) the movies we know by heart. You've seen the film, now read the book - or, at least, read the testimonial of someone crazy to give the books a shot!