Hollywood & Spine Archive: Another Galaxy, Another Time

An overview of the novelization to STAR WARS, originally published in May 2022.

Tomorrow is Orthodox Star Wars Day. I don't celebrate May 4, but the original release date of May 25? Come on now. The Star Wars novelizations - I had a thick paperback of all three in one binding from a young age - were a big catalyst of my love for the practice. As with so many of these, I could've gone twice or even thrice as long. Luckily for you, I didn't. (Originally published 5/25/2022)

Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Skywalker by George Lucas (pseudonym for Alan Dean Foster) (based on the screenplay by Lucas) (Ballantine Books, 1976)

The pitch: A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away...oh, you know.

The author: Though writer-director George Lucas has gotten credit on all printings of the book, he's never been shy about giving due credit to Alan Dean Foster, a titan of the prose adaptation whose work (and personal retrospective) we've gladly covered.

The lowdown: Recently, when talking to a friend about E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial's impending 40th anniversary (my friends are patient), I repeated my long-held gratitude that there's not a lot of lore surrounding the film. (Sure, there's a sequel novel, but a lot of details to the film, from the family surname to where exactly they live, have long been graciously glossed over.)

Inevitably, we juxtaposed this to Star Wars, a franchise seeking to fill every space of its galaxy with facts and tales - perhaps triply so, since The Walt Disney Company took over. (The latest, a show following Obi-Wan Kenobi set between the prequel and original trilogies, premieres this week.) I'd be foolish to put myself above the enjoyment of such Expanded Universe content: I've read handbooks and novels and comics, seen every spin-off film, ridden the theme park rides, followed many of the TV series and even lost countless hours to Wookieepedia. Many of these things have occurred during periods where I've paid for my own living expenses.

And I'm not alone. George Lucas' cinematic galaxy is the stuff of nine-year-old boyhood dreams: epic good-versus-evil writ large, with delights for the eye and ear. Since my father took my brother and I to see the original Star Wars - gussied up with digital effects in 1997 for its 20th anniversary - I've been some level of hooked, even as I've silently admitted I'd be fine if we never talked about it for a decade.

It makes perfect sense, then, that the first work to fill in the blanks around the first film is one of the few things that can, as an adult, spark that joy I first felt a quarter-century ago. Alan Dean Foster's novelization - released a full six months before the film premiered in a measly few dozen theaters nationwide - captures the spark of what made Star Wars so enchanting to the young (and young-at-heart) in 1977, before a single Constable Zuvio action figure sat on a peg at your local Target.

Not that you should be surprised. Foster would be the first to tell you that so much of the expansive prose and pacing of his book came from Lucas' screenplay and already vivid world-building. All he had to do was put it to page. But if that seems easy now, it's only because Star Wars is essentially part of our DNA. If you picked up this book in 1976, all you'd have to entice you was the stylized jacket art by Ralph McQuarrie, depicting a long-snouted Darth Vader glowering over a flaxen-haired Luke Skywalker and early, conceptual versions of Chewbacca, R2-D2 and C-3PO. (John Berkey's art for U.K. printings, while closer to the proof of concept, is also appealingly broad.) Forget John Williams' score and Ben Burtt's sound design!

The pleasure, then, is reading accounts of Star Wars mainstays we all know and love and picturing what the words show us instead of what we've known for generations. Take, for instance:

It consisted primarily of a short, thick handgrip with a couple of small switches set into the grip. Above this small post was a circular metal disk barely larger in diameter than his spread palm. A number of unfamiliar, jewellike components were built into both handle and disk, including what looked like the smallest power cell Luke had ever seen. The reverse side of the disk was polished to mirror brightness. But it was the power cell that puzzled Luke the most. Whatever the thing was, it required a great deal of energy, according to the rating form of the cell.

[...]

Luke examined the controls on the handle, then tentatively touched a brightly colored button up near the mirrored pommel. Instantly the disk put forth a blue-white beam as thick around as his thumb. It was dense to the point of opacity and a little over a meter in length. It did not fade, but remained as brilliant and intense at its far end as it did next to the disk. Strangely, Luke felt no heat from it, though he was very careful not to touch it. He knew what a lightsaber could do, though he had never seen one before. It could drill a hole right through the rock wall of Kenobi's cave - or through a human being.

What a majestic description of a device we all know and have seen in many iterations on film since. Here's another:

Two meters tall. Bipedal. Flowing black robes trailing from the figure and a face forever masked by a functional if bizarre black metal breath screen - a Dark Lord of the Sith was an awesome, threatening shape as it strode through the corridors of the rebel ship.

It goes on and on, great and small: the "almost comical quasi-monkey face," "large, glowing yellow eyes" and "soft, thick russet fur" of Chewbacca; the "battered ellipsoid which could only loosely be labeled a ship...pieced together out of old hull fragments and components discarded as unusable by other craft" that we know as the Millennium Falcon, the "tickling inside [Luke's] head" that represents his climactic, Force-assisted Death Star trench run. Foster's graceful prose paints vivid pictures that he was tasked with writing only from a thick script, some paintings by McQuarrie, and a quick visit out to Industrial Light & Magic as they toiled on the film's special effects.

"I [read the script] in increasing surety that at least half of what was on the page would never, as depicted in the screenplay, actually make it to the screen," Foster wrote in The Director Should've Shot You, his memoir. "But if it did, if it did, I decided it might amount to something more than just a fun film to watch on a lazy Saturday afternoon in a theater." Talk about the Force!

It's books like Foster's Star Wars that remind you of the joys of novelizations in the first place. As we thrill - whether in public or in resigned semi-secret (who, me?) - to the real-life Star Wars galaxy constantly expanding, it's fun to revisit the early quirks of Lucas' universe before they were fully organized. And that's from the smallest details (using an apostrophe before "droid," stating Darth Vader's lineage as a Sith before it meant anything to the larger narrative) to the biggest, which you'll read about below.

The cutting room floor: Hardcore Star Wars fans might know that one of the make-or-break decisions of the film's post-production involved sacking original editor John Jympson (A Hard Day's Night, Frenzy) and hiring the trio of Paul Hirsch, Richard Chew and Lucas' then-wife Marcia to cut the picture together. (Their Lucas-approved "faster, more intense" approach earned the film one of seven Academy Awards.) In the late '90s, official magazine Star Wars Insider and the making-of CD-ROM set Star Wars: Behind the Magic detailed some of this footage for the first time - not only excised scenes, but considerable alternate and extended sequences, too - and fans got to realize how this initial chain of events informed the structure and content of Foster's adaptation.

But before we get into that, we should point out Foster's incredible prologue, which sets up the political plot at the center of the Star Wars universe to great effect. In a few tantalizing paragraphs, the prosperity and subsequent decay of the Old Republic is outlined, two decades before it drove the narrative of a second Star Wars trilogy:

Aided and abetted by restless, power-hungry individuals within the government, and the massive organs of commerce, the ambitious Senator Palpatine caused himself to be elected President of the Republic. He promised to reunite the disaffected among the people and to restore the remembered glory of the Republic.

Once secure in office he declared himself Emperor, shutting himself away from the populace. Soon he was controlled by the very assistants and boot-lickers he had appointed to high office, and the cries of the people for justice did not reach his ears.

Obviously that played out a little differently in the prequels, but Palpatine wasn't even named on-screen until those later films - so the link between prose and picture, past and future is quite stunning. Also stunning is how, as in Jympson's original cut, the book's early action cuts between the Imperial capture of Princess Leia and Luke Skywalker's humdrum life on the planet Tatooine, before he encounters R2-D2 and C-3PO. His misfit status among his fellow teens at the fabled Tosche Station is apparent, with only the heroic pilot Biggs Darklighter, whom he idolizes, showing him the time of day. Biggs and Luke have a heart-to-heart about the former's decision to defect from the Imperial flight academy in favor of joining the Rebel Alliance - the first attempt to shake Luke off the fence he's sitting on living with his moisture farmer aunt and uncle. (This comes full circle in both the book and the Special Edition when the pair reunite before the final battle over the Death Star; the novelization adds a fun little detail that the X-wing squadron's leader once flew alongside Luke's father, who, we must stress, no one in real life yet knew that he would become the story's central villain Vader.)

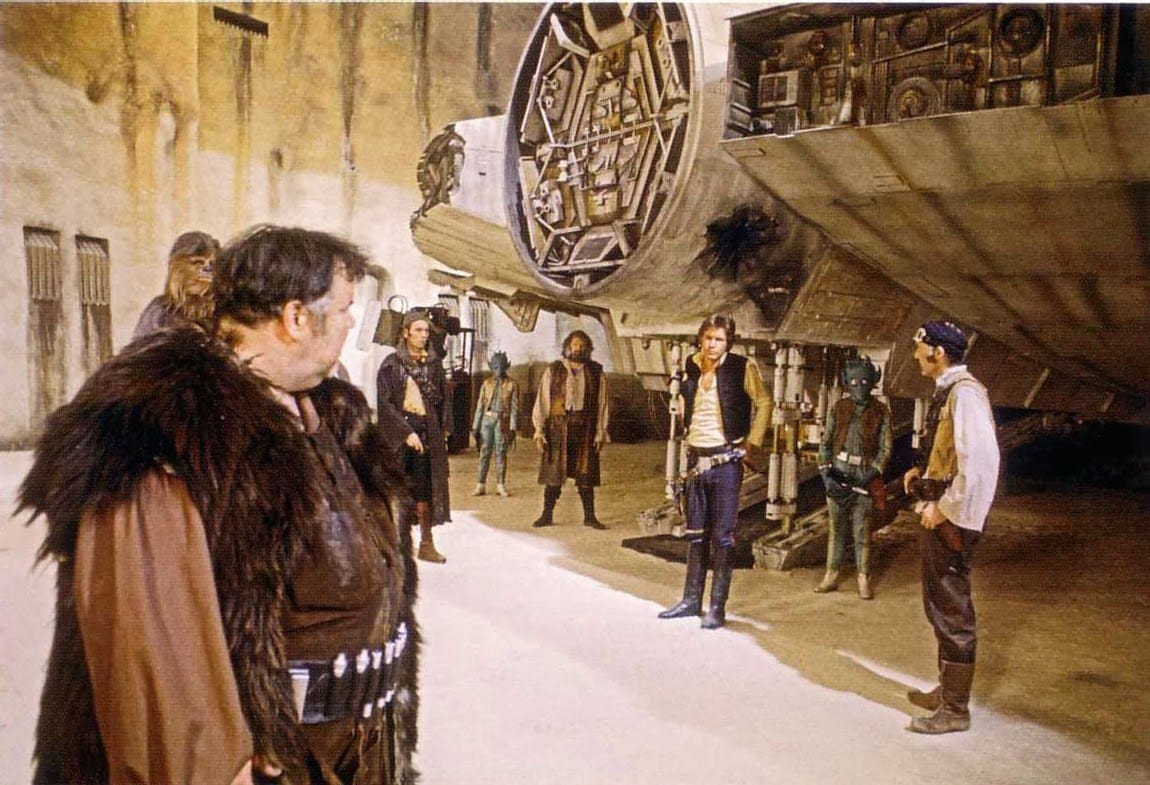

The other big cut scene added back into the picture is also intriguing in its minutiae: the smuggler Han Solo meets up with "a great mobile tub of muscle and suet topped by a shaggy scarred skull," unmistakable or not as Jabba the Hutt (here spelled with one "t"). And there's myriads of other odd little details in Foster's pages. Let's send you off with five!

- The Rebel pilot squadrons are color-coded Blue (X-wings) and Red (Y-wings) instead of Red and Gold as in the films. This likely had something to do with blue-screen effects.

- The unlucky stormtrooper that Luke disguises himself as on the Death Star is not call-sign TK-421, but - hold for laughter and applause - THX-1138.

- The wise Jedi Master Obi-Wan Kenobi is a wild character throughout: he lives in a cave, not a hut; he compares piloting skills to a duck learning how to swim, confusing the duck-ignorant Luke; he never senses the destruction of Alderaan; and he doesn't sacrifice himself to Vader's lightsaber blade so much as their duel just sort of ends with his demise (which he nonetheless predicts will make him "more powerful than [one] can possibly imagine."

- Han alludes to a smuggler friend named Tocneppil, which is Foster's way of shouting out Charles Lippincott, who headed Lucasfilm's advertising and publicity wings at the time. (If you got way hyped about Star Wars merchandise in the series' first year, you probably have him to thank!)

- Long before Carrie Fisher herself righted the wrong at the 1997 MTV Movie Awards, the novelization establishes that Chewbacca received a medal alongside Luke and Han.

The sequel? Foster was contracted for one additional Star Wars book, also a wild read. Splinter of the Mind's Eye was conceived as a backdoor TV-movie sequel had the film bombed (ha!); in it, Luke, Leia, Artoo and Threepio (not, pointedly, Han or Chewbacca, as Harrison Ford wasn't contracted for a sequel) are stranded on the planet Mimban (later briefly glimpsed in the spin-off film Solo: A Star Wars Story) and eventually seek a Force totem known as the Kaiburr crystal. (This detail was also since officially canonized: a kyber crystal is what gives a lightsaber its colorful blade.) "I understand why, thematically, it fell by the wayside," Foster later wrote of the sequel that never was. "Would've topped the holiday special, though."

The last word: Star Wars, as adapted for the page by Foster, is a fascinating glimpse of different worlds - not just the ones created by Lucas, but a world before the series only had the potential, not the execution, to be the stuff of massive myth it is today. Reading it, you may catch yourself metaphorically glimpsing toward the setting suns of Tatooine, pondering the infinite of what could have been.