Hollywood & Spine Archive: Back to Back, Vol. 1

An overview of the novelization to BACK TO THE FUTURE, originally published in June 2020.

Getting to the Back to the Future series was an early goal of Hollywood & Spine thanks to the work of Ryan North (and my tiny, tiny contribution to it) noted later in this essay. It's such a fascinating novelization, maybe the best kind: it certainly looks mostly like the source material, but the more you look at it, the more you realize that may not be as correct as you thought! Also, looking back at this period (and the next few months leading up to me losing a job in the summer of 2020, honestly), I can't believe I wrote as many of these damn things as I did! (originally published 6/10/2020)

Back to the Future by George Gipe (based on a screenplay by Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale) (Berkeley, 1985)

The pitch: A charismatic teenager with a lot of time on his hands goes on an incredible adventure into the past, helping his parents to fall in love in the process.

The author: George Gipe (1933-1986) was not only a writer of novelizations but screenplays as well, co-writing Dead Men Don't Wear Plaid and The Man with Two Brains alongside Carl Reiner and Steve Martin. BTTF was one of three effects-heavy '80s movies he adapted for prose, along with Gremlins and Explorers; a year later, he unfortunately died of a bee sting.

The lowdown: The runaway success of Back to the Future is, with 35 years of hindsight, not all that surprising. As a popcorn film, it's got everything: charismatic, star-making performances; a high concept bolstered by an airtight script; dazzling feats of action, comedy and a splash of science fiction; and eye-popping special effects, to boot.

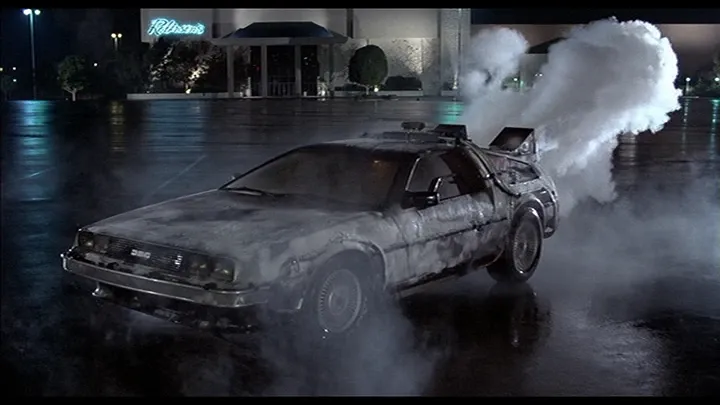

But what really made the story endure - like, "three films, a cartoon series, a theme park ride, some comic books and video games, and acres of ancillary merchandise" endure - has to do with the things you might not see on first viewing. Under the hood of that souped-up DeLorean time machine rests a deeply human story that asks complex questions: how well do we know our families? How do people acquire their traits, and how do those traits influence their descendants? How quickly can a person's outcome change, and what does one have to do to make it so?

And, for our purposes: how much of that energy can a book version of BTTF capture?

Unsurprisingly, the life behind the movie imitated its space-time continuum-altering art as it took shape. Certain decisions were made then unmade, any of which would have drastically changed the film we know. Early screenplay drafts featured a time machine made out of a refrigerator and powered by Coca-Cola. The film was almost unappealingly renamed Spaceman from Pluto until an intervention from producer Steven Spielberg. Eric Stoltz completed a good chunk of filming (maybe more than is often realized) as the heroic Marty McFly before writer/producer Bob Gale and writer/director Robert Zemeckis secured Michael J. Fox, their first choice for the role. (Stories like these can be found in Michael Klastorin's official books on the series, as well as Caseen Gaines' incisive, unofficial-but-should-be We Don't Need Roads. I was delighted to interview Caseen not long after the book's release in 2015.)

Reading the lengthy, shaggy-dog novelization of Back to the Future is very much like stumbling on an alternate timeline where most of the early draft picks took place unchallenged. It is far removed from the final film's sugar-coated Saturday morning breakfast treat style. No story beats change, but had they been executed on film the way they are in the book, Marty McFly's story would have been a cult classic, not a cornerstone of blockbuster film.

Gipe's prose characterizations of Gale and Zemeckis' script simply don't crackle. His often leaden word choices bog down moments that feel effortless in the finished film, and characters' actions are often accented with frivolous passages where our heroes literally speak their inner thoughts out loud to no one.

Consider one of my favorite exchanges in the film: Marty assesses his situation stuck in 1955 as "heavy," to his scientist friend Doc Brown's exasperation. Doc replies: "There's that word again: 'heavy' Why are things so heavy in the future? Is there a problem with the earth's gravitational pull?" Marty responds to the question with bewilderment, and Doc snaps right back into assessing his young friend's situation, offering a short laugh on top of a broader one.

Here's how that gag plays out in the book:

"Jeez, Doc, that's pretty heavy..." Marty said.

"There's that word again," Doc Brown replied with a shake of his head. "Heavy. Why are things so 'heavy' in the future? Is there a problem with the world's gravitational pull?"

"Huh?" Marty said.

Doc smiled. He enjoyed confusing his young friend occasionally. But rather than try to explain the remark or try to add to Marty's confusion, he jumped ahead to another aspect of the Lorraine-George dilemma.

Imagine if "Who's on First?" had been written that way! And this happens throughout the book, when Marty thinks his band audition at the beginning of the story might be cancelled and says "No! Don't let it be that!" in an empty hallway, or when Doc arbitrarily "spun around and fell backward," never receiving an electrical charge, after his daring last-second connection of cables to get 1.21 gigawatts to power Marty and the time machine back to 1985. We typically associate with Back to the Future with more brevity and wit than is on display here - but as is so often the case with, the book unwittingly encourages us to appreciate the film a new way, by reminding what could have happened less successfully.

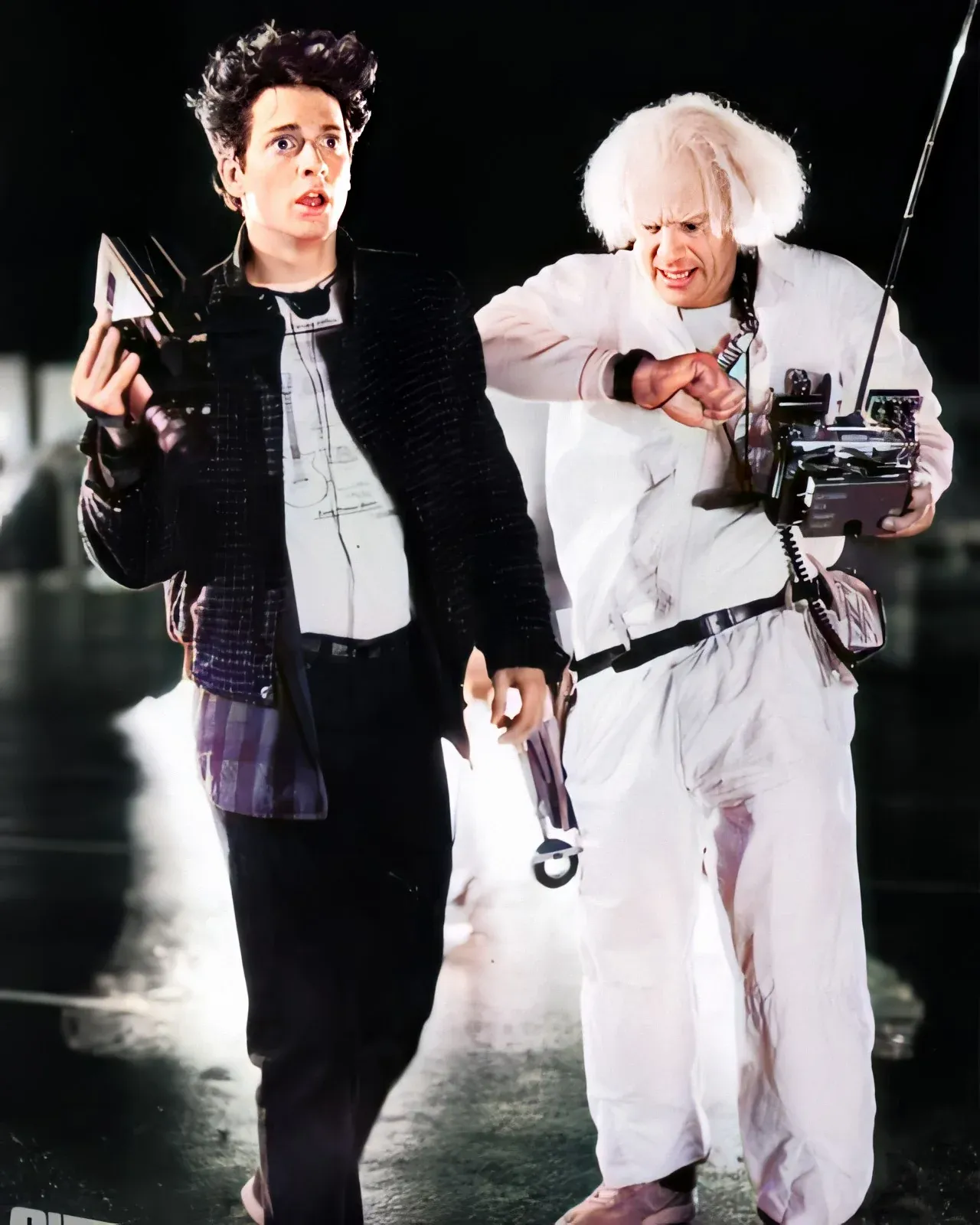

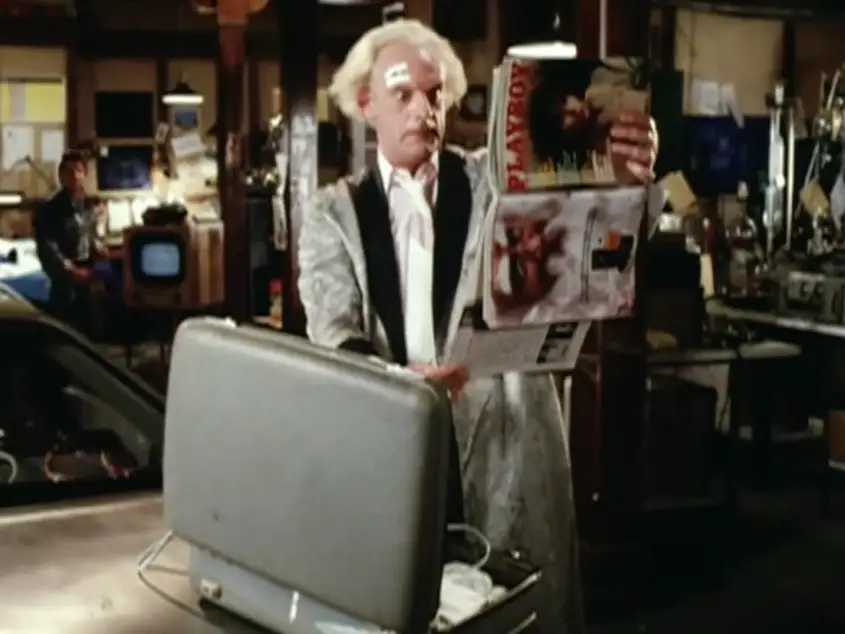

Gipe's prose also contributes to a sense of unfamiliar characterization, too. That's to be expected with novelizations: authors usually don't get to see any of the final film, so they can't always predict the choices the cast will make. But our dynamic duo feels unfinished: in the book, Marty possesses a much slyer, slicker characterization instead of the aw-shucks every-kid energy Fox delivered (becoming a major movie star in the process). Christopher Lloyd's brilliantly unhinged Doc Brown was not simply laying in wait on the pages of the script, either. Gipe gives him a strange, almost fatherly tone only only partially fueled by the manic energy that Lloyd possessed - a better fit had Gale and Zemeckis cast John Lithgow, their first choice for the character. (I think we get one "Great Scott" in the whole book.)

Perhaps it's because they're "only" supporting characters, but Marty's parents fare better by comparison. Reading their actions and dialogue, it's much easier to picture Lea Thompson and Crispin Glover's performances as the coy, charming Lorraine Baines and the awkward nerd George McFly. (George even gets a fascinating extra shade in the book, wanting to study writing at a collegiate level but discouraged by his own father.)

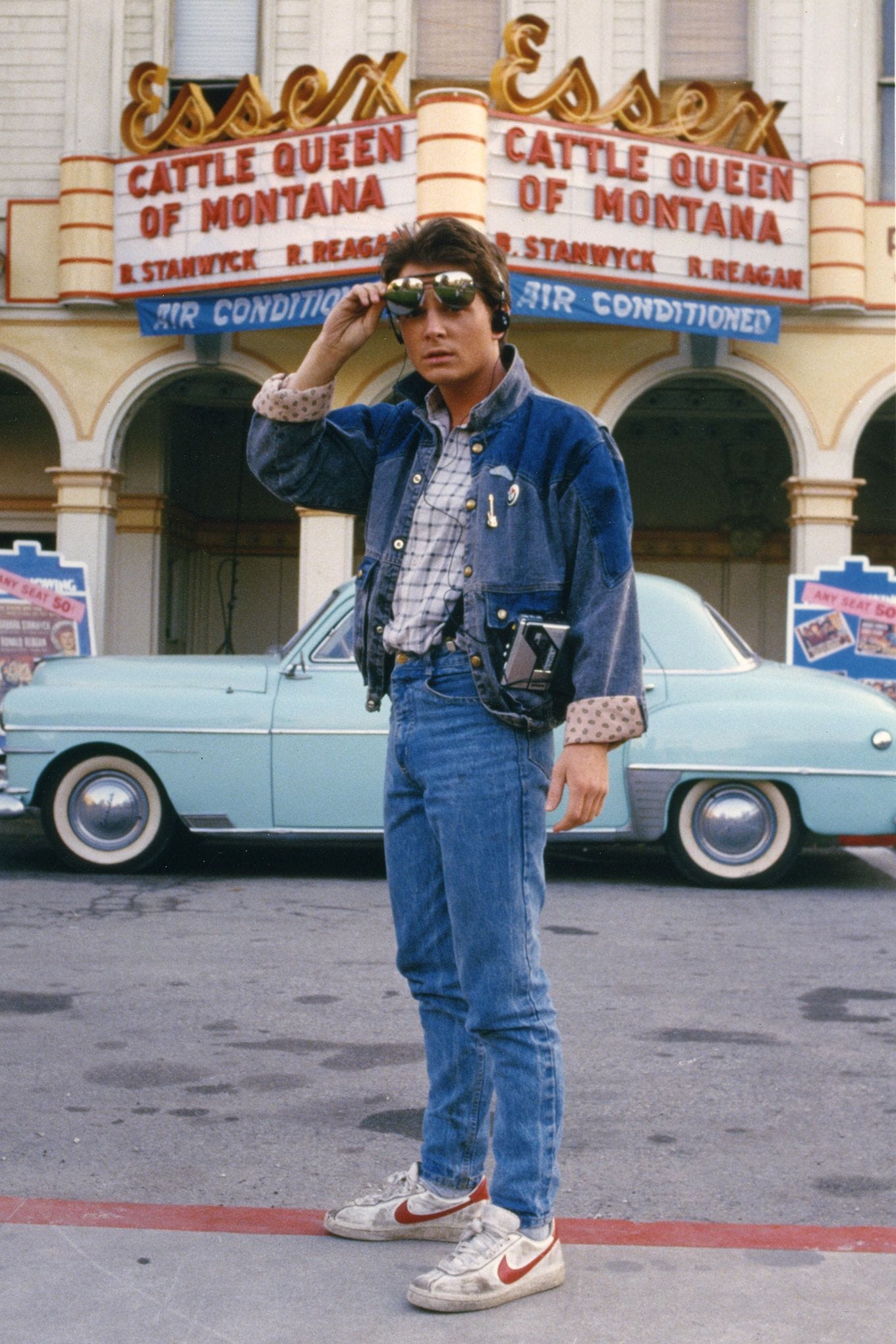

All of which begs the question: what could have possessed Gipe to make these choices? He's not around to explain, sadly, but the choice seems clear: he almost certainly started writing before Fox replaced Stoltz as Marty. Thus, readers will miss things like the jokes about McFly's '80s puffy vest and acid-washed denim wardrobe. (Noted comic author Ryan North did a page-by-page assessment of the BTTF novelization many years ago, later collated into an e-book. I realized that I am absolutely the Mike who wrote him in this post suggesting Gipe's descriptions of Marty's 1985 clothes - a U.S. Patent Office t-shirt and green shoes - are based on Stoltz's wardrobe. Hollywood & Spine was a long time coming.)

The cutting room floor: Back to the Future's deleted scenes became coveted by fans early on, not only because of this novelization but a 1990 promotional tape, Secrets of the Back to the Future Trilogy, that actually showed a few of them.

But things are different from the first page: we first meet Marty not in Doc's lab but in school, listening to his Walkman instead of watching a filmstrip about nuclear power. Doc calls him over the school system's phone to beckon him to his latest experiment at the Twin Pines Mall that night; the call lands Marty in detention, where the disciplinarian Mr. Strickland confiscates Walkmen and crushes them in a vise. If that isn't silly enough, Marty escapes the class (and gets to his band audition) through a MacGyver-esque plot involving slingshotting a book of matches toward a smoke detector and using angled sunlight to set them ablaze.

Many of the other deleted scenes are additional set-up/payoff moments. The henpecked George McFly is coerced into buying a case of peanut brittle from a neighboring Girl Scout, underlining his wimpy qualities (and providing a laugh to Marty's stonefaced reaction to being offered peanut brittle at the dinner table in the final film). The Doc Brown of 1955 investigates his future self's personal effects, including a hairdryer that Marty brandishes when convincing George to ask Lorraine to the school dance. And Marty's plan to make George and Lorraine fall in love at the dance hits a extra snag when an agitated George attempts to use the boy's room and gets locked in by the same redheaded bully who tries to cut in on the couple's dance later in the film.

One of the briefer but more notable character moments that appears in the book but not the film is Marty's own unease about sending his demo to a record company. In the book, at his lowest point in 1985, we see him throw the tape away, only to change his mind when he makes it back to his own time. (You can see Marty carrying the envelope into his kitchen in the final film.)

The last word: Ironically, the novelization of Back to the Future is a fascinating lesson in how your own actions affect events to come. A must for BTTF die-hards, but casual fans who (rightly) adore the movie might not want their memories challenged by this strange alternate take on one of Hollywood's most beloved stories.