Hollywood & Spine Archive: Eighth Wonder

An overview of the novelization to KING KONG, originally published in March 2020.

King Kong is one of my five favorite movies, and the novelization is notable as one of the first major prose adaptations to accompany a blockbuster of such size. The fact that so many of these books are based on sci-fi, horror and fantasy films can largely be traced to Kong. I'm not so sure if I conveyed the gravity of that in this piece, but looking at the publication dates, this was one of the first things I wrote after my first and worst bout with COVID-19. (Originally published 3/26/2020)

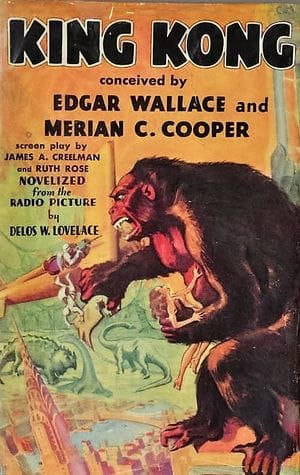

King Kong by Delos W. Lovelace (based on the screen story by Edgar Wallace and Merian C. Cooper [and the screenplay by James Ashmore Creelman and Ruth Rose]) (Grosset & Dunlap, 1932)

The pitch: A daredevil filmmaker, his leading lady and the crew of their charter ship head to a mysterious island and discover something more shocking than any motion picture...

The author: A journalist turned short-fiction writer, Delos W. Lovelace(1894-1967) got the Kong gig through his personal connections to the film's director, Merian C. Cooper. (Both men were former college roommates and employees of the Minneapolis Daily News.) Lovelace got a princely $600 for his work and would later write biographies of luminaries like Dwight D. Eisenhower and Knute Rockne.

The lowdown: As a film, there are things about King Kong's creation that still spark my imagination as much as they did when I was first captivated by the giant ape as a young boy in school. Modelmaker Willis O'Brien's unbelievable stop-motion animation brought the fearsome ape to terrifying life in a way that bigger budgets and more advanced special effects could not. In a time of economic downturn, audiences flocked to the film; in its first four days of exhibition at the 6000+ seat Radio City Music Hall, Kong sold out 10 screenings at a 35-to-75-cent ticket price. I hope I don't need to convince you what a watershed film it is, but if you've not seen it, do so as soon as possible. Its charms endure nearly 90 years after it was first put forth in movie houses.

Imagining the thrill of seeing Kong in 1933 - and, presumably, asking oneself "How on earth did they do it?" through the latter two thirds of the feature - makes the novelization, which cannily predates the film's release, feel like a small-scale daredevil promotion. "Folks," the book would challenge, "this story is about a crew of adventurers discovering a remote island populated by dinosaurs and a giant gorilla - and then that gorilla rampages through New York! So that's all going to be a movie in a few months, if you can even picture that." And I bet I couldn't!

Funnily enough, I don't think that's entirely what Merian C. Cooper and Delos Lovelace had in mind when putting Kong on bookshelves before bijous. If anything, the publishing date is likely a lingering side effect of Edgar Wallace's involvement on the Kong project. A prolific thriller writer in his native England, Wallace was called upon to put Cooper's giant ape idea into a workable script; within weeks of turning in his draft, he died of a sudden illness. (It was primarily Ruth Rose, wife of Kong co-producer/director Ernest B. Schoedsack, who whipped the screenplay into filmable shape, but Wallace's name value was apparently too great to omit.)

Whatever the reason for Kong's advance publication, Lovelace's book admirably does what all good novelizations seek to do: translate a screen story into prose. That's what you get here over a breezy 150 pages. One is not afforded insight into the mighty Kong's psyche, nor anyone else's for that matter (save for a brief sentence where leading lady Ann Darrow and first mate Jack Driscoll's backstories are summarized as they engage in courtship on the long expedition). The dialogue is a bit woollier than the final product - there's certainly more of it - and there are plenty of details that don't look exactly as they do in the film. (Most notably: the ship here is called the Wanderer, not the Venture; the film's Chinese cook Charlie is replaced by the grizzled, monkey-toting sailor Lumpy. Both appear in Peter Jackson's sprawling remake, as does one of the only other named sailors in the book, a young man named Jimmy, who here presumably dies from a dinosaur attack. It's never really established.)

If the book's pace is too punchy, it's once the action moves from Skull Island to Manhattan. Kong's infamous rampage through New York really isn't so on the page, and there is little time (a few pages, really) to savor his final stand atop the Empire State Building. It's almost as if spending so much time on an exotic island with a large ape and dinosaurs was fantasy enough, and Lovelace offered to keep the film's final hand firmly hidden from the audience.

The cutting room floor: The most notable structural difference of Kong the book is the inclusion of its most famous deleted scene. Originally, the sailors' fateful expedition on Skull Island was to end in multiple climactic nightmares: a triceratops gives them chase, then the men are stuck on a log over a ravine which Kong attacks, and all the sailors save Denham and Driscoll either fall into the ravine to their death or are consumed by hideous spiders in said pit. Ultimately, only the log bridge and ravine fall figured into the final cut of Kong, and footage of the other natural antagonists has long been presumed lost. (Ever the obsessive, Peter Jackson not only updated the spider pit sequence for his version, but used stop-motion animation to imagine the original sequence in a DVD extra.)

The last word: Lovelace's King Kong is a triumph in itself for simply being one of the first mainstream books to do the work of translating a screen story (and a pretty ambitious one) into something you can read over and over. That its most recent printing was part of Penguin Random House's Modern Library Classic series - with some very intriguing backstory on the book's creation, to boot - is a sign of how towering King Kong truly is.