Hollywood & Spine Archive: Gonna Fly Now

An overview of the novelization to ROCKY, originally published in January 2019.

Thanks to everyone who's signed up for Duque's Delight so far! If you've subscribed at the Hollywood & Spine level or higher, you'll get more than 60 sends over 2024 from the newsletter archive, plus some new essays too! (The next new one comes next month: a look back at the recently published English translation of Shigeru Kayama's novelization of Godzilla, which turns 70 this year.)

I don't remember what compelled me to start Hollywood & Spine proper with Rocky, one of my five favorite films of all time - but I'm proud to say the concept was more or less fully formed from the start. The "devil in the details" header is something I largely abandoned over time; I guess I wanted to specifically point out a notable change that had no precedent in the original source material - a thing I quickly realized might not be interesting enough to engage every time. I've said this a lot to friends, but I try to actively resist what I call "Novelization Def Jam": the book does this, and the movie does this. (Originally published 1/14/2019)

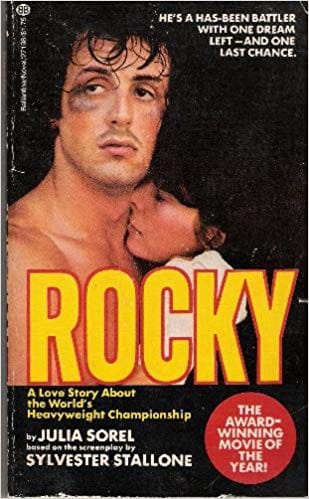

Rocky by Julia Sorel (based on the screenplay by Sylvester Stallone) (Ballantine Books, 1976)

The pitch: an amateur boxer from Philadelphia gets the chance of a lifetime in the first in a sports drama franchise that’s carried on for more than 40 years.

The author: “Julia Sorel” was actually Rosalyn Drexler, an award-winning playwright, novelist, pop artist and—this may have clinched her the job adapting Rocky—former professional wrestler. (While performing under the name Rosa Carlo, Andy Warhol created a series of silkscreen paintings based on her image in 1962. Drexler hated this part of her career, but wrote 1972’s acclaimed To Smithereens based on her experiences.) As Sorel, she penned a novel, Unwed Widow, and had recently adapted the NBC TV-movie Dawn: Portrait of a Teenage Runaway (starring Eve Plumb of The Brady Bunch) into book form; a year later, she’d do the same for a sequel, Alexander: The Other Side of Dawn.

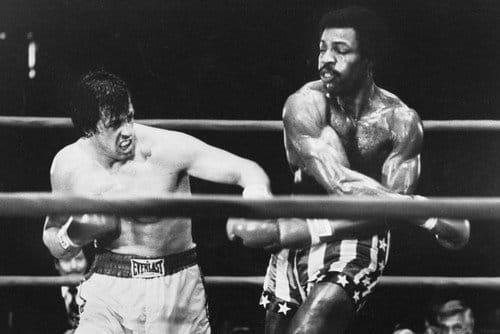

The lowdown: Whether a by-product of its against-the-odds creation or just dumb luck, Rocky Balboa and Sylvester Stallone are forever intertwined. The struggling actor’s screenplay about a southpaw slugger and his million-to-one shot was well-appraised by Hollywood, but the actor valiantly held out from selling it until he was guaranteed the lead role, as well. Until 2015’s stirring reboot Creed, where Balboa ceded the spotlight to train the heretofore-unknown son of rival-turned-friend Apollo Creed, Stallone had been the sole writer of Rocky films and had directed four of the six entries in the franchise.

So Rocky the novelization, like so many books we’ll tackle in Hollywood & Spine, has this challenge in the other corner of the ring: how does the style, the essence of what we see on screen look when adapted to the page? Stallone spent part of his adolescence in Philadelphia, and clearly had a fondness for the City of Brotherly Love enough to make it Rocky’s home base, a sort of geographic, junior-varsity spinoff from Martin Scorsese’s grimy Manhattan.

There are passages of Rocky the novel where the grime is dialed up even more than the film. Balboa’s fleabag apartment, the dingy bar he frequents—there’s a darkness on paper that Rocky doesn’t quite sink into on film. For instance, Balboa’s famous attempt to give neighborhood girl Marie some advice famously ended on screen with her shouting “Screw you, creepo!” at the fighter; here, it’s a full-on “fuck you, motherfucker!”

This bleak style extends to the basic, almost Sisyphean prose describing Rocky’s training—not a single step from the Philadelphia Museum of Art is featured—as well as the book’s (and original script's) drawn-out ending, where the Balboa-Creed decision and Rocky and his girlfriend Adrian’s cathartic reunion play out separately instead of simultaneously, as the film’s emotional finale.

The devil in the details: Most novelizations, of course, find their length with unique details or character moments included only as directions in the screenplay. Here, the most striking alterations are given to the underestimated Adrian and her brother Paulie, Rocky’s best friend. Their surname in the novelization is “Klein,” more than a cosmetic departure from the film’s “Pennino”; it hints at a cultural identity that the book doesn’t care to touch on (compared to the often explicit pride of "The Italian Stallion" and his extended family throughout the franchise).

There’s also a crucial shade to Rocky and Paulie’s friendship that’s touched on early in the novelization and nowhere else in the series:

Czack, wiping the bar where some beer had spilled on its varnished, deep brown surface, appealed to Rocky on Paulie’s behalf. “Why don’t ya let ‘im work ya’ corner again, Rocky?”

Curtly, Rocky replied, “Can’t do it.”

“So he laid a few bucks against ya.” Czack flipped the bar towel over one shoulder and leaned forward, closer to Rocky in a confidential manner.

“Yo, Paulie is my friend but i can’t never forget he bet against me—that really hurts, y’know,” Rocky said, fingering a sore spot beneath one eye.

I’m not sure if this makes Paulie’s character worse or Rocky’s consistent altruism toward his friend and future brother-in-law even more sympathetic.

The cutting room floor: With novelists at the time working from a shooting script more than anything, a novelization will often showcase scenes that don’t end up in the final cut. Rocky’s most famous is a mid-training encounter with both Apollo Creed (who is written as 28, far younger than in the film) and Dipper, the fighter who inherits Balboa’s locker at the start of the film. (Publicity stills indicate this scene was filmed, though wisely left out.)

With commentator “Steward Nehan” looking on (he’s referred to earlier in the book as a “college moron, a silver-haired jock who was thirty years past his false prime”—hardly a flattering account of real-life commentator Stu Nahan, who appeared in all six Rocky films), Dipper accosts Rocky’s unearned lucky streak, cursing the challenger until he’s laid out by Balboa. It’s an interesting scene, but it deflates Creed’s arc; here, he considers his challenger “with admiration and a hint of apprehension,” instead of focusing on the spectacle and discovering Balboa’s drive only when he’s fighting him, as in the film.

Another bizarre extension of a scene comes in before the Balboa-Creed fight, when the fighters are greeted by not only Joe Frazier (who cameos in the film), but Jack Dempsey, Jake LaMotta and Joe Louis, as well. Perhaps Stallone was aiming high for real-life pugilistic talent and taking whatever he could get!

The verdict: The rough edges of Rocky as a novelization (and, inevitably, the script) were smartly sanded off to create a blockbuster crowd-pleaser (with sequels still drawing crowds as recently as last November's Creed II). But even in its rougher prose form, Rocky is still a knockout (and, at 138 pages, a swift KO at that). Like many mass-market novelizations of its time, you can fetch it for a couple bucks used; cue up the Bill Conti and enjoy this alternate look at a pop film classic.