Hollywood & Spine Archive: I Like to Read in America

An overview of the novelization to WEST SIDE STORY, originally published in January 2022.

It should not surprise you in the slightest, given my other work and writing, that one of Hollywood & Spine's sub-plots is exploring the mystifying chasm between sound and page. Reading a movie is one thing; reading a musical is an entirely other weird thing. I remember being baffled as I read this. It really is like seeing a musical with all the songs cut out! Not quite beautiful chaos, I'm afraid. (Originally published 1/18/2022)

West Side Story by Irving Shulman (a novelization of the Broadway musical based on a conception of Jerome Robbins; book by Arthur Laurents; music by Leonard Bernstein; lyrics by Stephen Sondheim; entire original production directed and choreographed by Jerome Robbins) (Pocket Books, 1961)

The pitch: Two teenagers - an white American boy and a Puerto Rican girl - try to unstick themselves from a New York street gang war and find true love.

The author: Irving Shulman (1913-1995) only wrote this one novelization, but was no stranger to writing about gangs and wayward youth. His Amboy Dukes novels were adapted into movies like City Across the River (1951) and Cry Tough (1959) - and his 1956 novel Children of the Dark drew from his work on the script for another iconic teen drama, the James Dean starmaker Rebel Without a Cause.

The lowdown: It finally happened. We found an honest to God musical novelization for Hollywood & Spine. Book adaptations of The Rose and Footloose got close, but this is a 150-something-page adaptation of a stage musical-turned-film. And not just any stage musical-turned-film - one of the most famous adaptations of one of the most famous musicals in history.

The long tail of West Side Story is explanation enough for why there's even a novelization in the first place: a 1961 film adaptation was the year's highest-grossing film, won a staggering 10 Academy Awards and put a soundtrack album on top of the Billboard charts for almost an unbroken year. (At the time, the magazine ranked top-selling mono and stereo albums, and the album topped either of those charts for all but two weeks between May 1962 and May 1963.) In 2021, Steven Spielberg attained a career-long dream of directing a new film adaptation of the production, hiring Tony Kushner to adapt the show's book for the screen and featuring dazzling performances and a cast of actual Latin-American actors to play the Sharks. And -

Alright, we're getting ahead of ourselves here. Strip away all the accolades and justification for a page-bound adaptation of West Side Story (one that was printed shockingly recently - the copy reviewed has a URL for Simon & Schuster's website on the back cover) and you're still left with the mind-bending proposition that a music-heavy, dance-intensive feature like West Side Story would be adapted into a medium with no music and no dancing. Consider that the show is a loose adaptation of Shakespeare's Romeo & Juliet, and you're left with an even more confusing proposition: it's a chapter book version of one of Western culture's greatest tragic love stories.

And does it work? You bet your ass it doesn't!

Something's coming, something weird: The ways in which Shulman's West Side Story translates its source material are fascinating in their misguided approaches. We know well from our time at Hollywood & Spine that sequences of lengthy action and little-to-no dialogue can be a real challenge to adapt. We've seen time and again how cognitive dissonance can arise from taking ideas from a script page - meant to be translated into visual language - and turning them into something one reads to picture in the mind's eye. But these passages are something else.

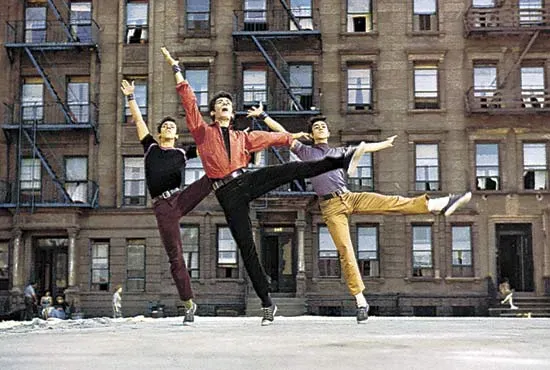

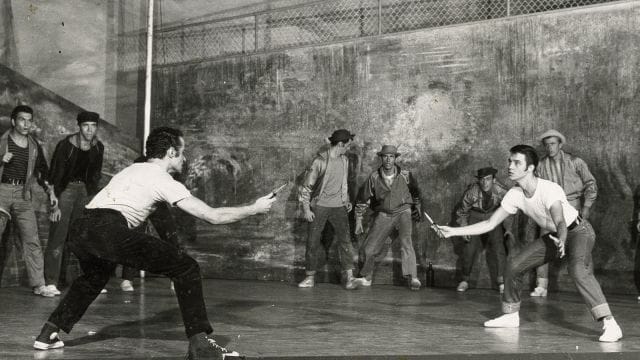

Take, for example, our beginning. From the very start of the musical - stage or screen - a stunning overture sets the scene for a mostly-wordless first encounter between the Anglo miscreants in the Jets and the Puerto Ricans that make up their de facto antagonists, the Sharks. It's a lyrical brawl that doesn't leave anyone entirely blameless, giving in to the ugly overtures of racism and misunderstanding that boil over into senseless violence.

The book's version of this? A woolly introduction to the toughs of the Jets, who assert their street dominance by stinkbombing a Puerto Rican bodega, with barely a Shark to be seen. There's more tell than show throughout the whole book: a series of escalated (but never seen) attacks on Jets by Sharks that prompts a climactic rumble, a mushy sense of mystery in former Jet leader Tony's retreat from gang life. ("Something to do with his old lady," Riff remembers in one passage, noting that his one-time best friend hasn't been seen with the boys for three or four months, since helping defeat a rival gang called the Emeralds.)

When the action shifts to the Sharks - Bernardo's fiery hatred, his sister Maria's wide-eyed innocence - it lacks the nuances of what an onstage performance might offer. Sure, Shulman is happy to fill in details a movie might not bother with, namely names: Tony Wyzek, Maria Nunez, Riff Lorton and so forth. But developing a sense of these characters and their motivations, in absentia of the musical numbers that did the work in the first place? It's hard to come by here.

Perhaps the oddest passage in place of a musical number is Tony and Maria's encounter in the bridal shop in which she works. In the musical, it's the set-up for their second duet together, the stately "One Hand, One Heart." In the book? The pair use mannequins as stand-ins for their parents' eventual meeting, imagining the encounter through hackneyed dialogue. The Sharks-related sequences perhaps fare worst of all, as the original show conveyed most of their story through numbers instead of dialogue. While the attempts are valiant - we see Maria and Anita push against some of the anti-American sentiment from the Puerto Rican boys where "America" would have been - they're often forgettable.

There's a prose for us: Sometimes Shulman's space-filling verbiage hits its mark. Tony and Maria's first encounter during the dance at the gym captures the surreal qualities of how it plays out in choreography. ("Maria felt that her heart might burst. Were the lights above them dimmed so that she could not see this Anglo boy with whom she danced? And why wasn't she frightened of him?") There's also pathos when Maria's overprotective brother Bernardo regards how Tony's stare at his sister "wasn't a dirty or a disrespectful look," but, to him, naturally carried the evil inherent in the "P.R."-hating Jets.

Steps are missed when the prose - intentionally or not - resembles Sondheim's lyrics in any way. "Her name was Maria," Tony's post-meeting monologue clunks. "a really beautiful name, one that made him think of all the most wonderful sounds possible." Elsewhere, Maria, in the throes of romance, feels "wonderful, marvelous and beautiful" - but never "pretty."

Perhaps the biggest missed opportunity is when the final paragraphs (after Maria's final dialogue over her dead love Tony, which is one of the few moments almost beat-for-beat from the musical) faintly recall the open-ended, against-all-odds hope of the show's signature "Somewhere":

And there were people who looked up at the sky and ached with loneliness, as they appealed in silence to the stars and the moon. They hoped that someplace, somewhere, heard them, tat their own little dreams would come true, that very soon they would meet someone they could trust, could love and be happy with.

Some of the wishes came true, but it made no difference to the city because it had been built to endure beyond the lifetime of all the people that inhabited it.

That is the way things were. And if things did not change, the way it would always be.

The last word: Not a hat worth finishing! West Side Story must be seen and heard more than anything.