Hollywood & Spine Archive: Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo, il libro

An overview of the novelization to THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE UGLY, originally published in February 2023.

I really wanted Hollywood & Spine to avoid simple genre/franchise retreads, and covering a '60s pop film like this one felt like a good move in the direction I wanted to go in. I saw The Good, The Bad and The Ugly when I was 16, in an Analyzing Cinema elective I took with my friends in high school, and it was probably the movie that resonated the most. Some classmates with otherwise very good taste were baffled by the cinematography and the score in particular, and I chafed against their disdain; luckily, I was rewarded by the imminent extended release on DVD and a soundtrack reissue that same year. It's not one I reach for as regularly as I'd like, but I'm always captivated by its charms, and it was fun to revisit here. (Originally published 2/22/2023)

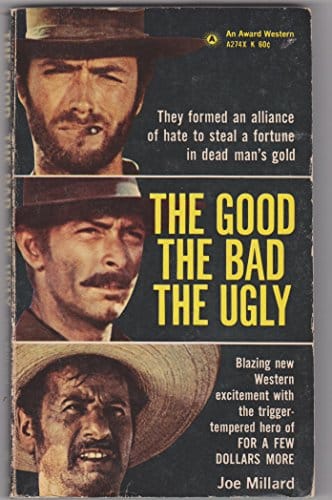

The Good, The Bad and The Ugly by Joe Millard (based on the screenplay by Age-Scarpelli, Luciano Vincenzoni and Sergio Leone) (Award Books, 1967)

The pitch: Set against the backdrop of the Civil War, three gunslingers - including "The Man with No Name," the bounty hunter from co-writer/director Sergio Leone's A Fistful of Dollars and For a Few Dollars More - chase after a buried fortune in the American Southwest.

The author: Joe Millard (1908-1989) was a writer and educator who'd recently adapted For a Few Dollars More for paperback. He would go on to write several original stories featuring The Man with No Name into the '70s.

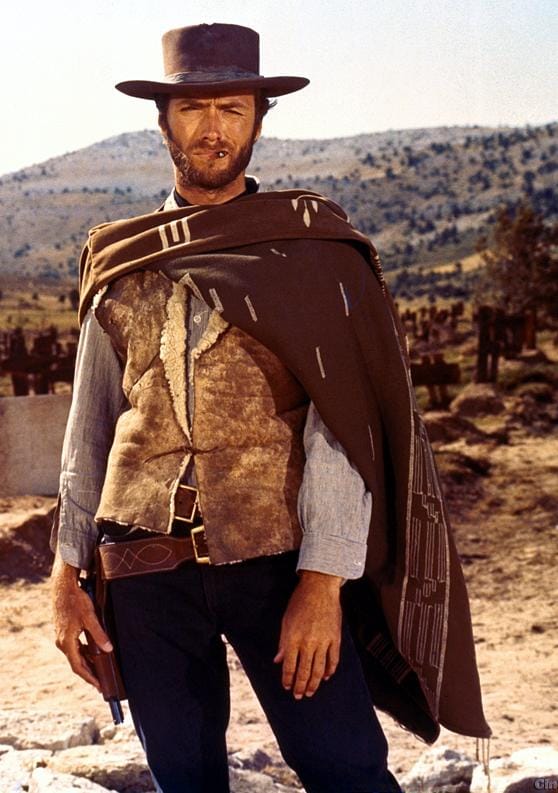

The lowdown: Sergio Leone first teamed up with Clint Eastwood on A Fistful of Dollars in 1964 - a modestly-budgeted Western shot across the plains of the director's native Italy. Though it kick-started the entire "Spaghetti Western" sub-genre of ultra-violent, ultra-stylized, European-made cowboy pictures, its cultural impact was initially minimal: a lawsuit from the makers of Akira Kurosawa's Yojimbo (which Dollars owes much of its narrative structure to) kept the film and its two follow-ups, each filmed a year apart, out of American cinemas until a 12-month stretch in 1967. And they were initially shunned by critics at the time. As is so often customary, audiences couldn't have disagreed more: each film was a blockbuster in America, and The Good, The Bad and The Ugly perhaps resonated the most, making back some 40 times its budget.

Maybe it's just nostalgia for a bygone era, but it's heartening to think about millions going to see a movie like this one. It traffics greatly in style and substance, from every performance in the film (chiefly Eastwood's near-silent gunslinger, Eli Wallach as his bawdy but captivating foil Tuco, and Lee Van Cleef as the steely nemesis Angel Eyes) to the dazzling editing and cinematography, the surreal visual language (two characters are captured twice by antagonists that materialize from the borders of the screen), a tremendous rock opera of a score by Ennio Morricone (the main theme, re-recorded by easy-listening bandleader Hugo Montenegro, climbed to No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100 - kept from the top by Simon & Garfunkel's "Mrs. Robinson"), and more heart than most action films, with the grim insanity of war offering evergreen subtext as more and more American troops began dropping into the conflict in Vietnam.

That's not to say the film is exactly an easy watch. Released in Europe at nearly three hours, initial U.S. prints cut 15 minutes from its running time. And everything happens with purpose and deliberation: you don't even hear a word uttered until more than 10 minutes in, and the mix of long takes and quick cuts is unique in its contradictions. You can imagine a novelization - in the pre-multiplex, pre-video era, a pure distillation of pomp prose and pulp - laboring too hard or not at all to strike the same high-low balance as its source material.

Maybe it was writer Joe Millard playing in the same sandbox as he did that year in his adaptation of For a Few Dollars More, the second of the Man with No Name flicks - but The Good, The Bad and The Ugly gives you everything you'd want from an adaptation of its generation: snappy style that befits the source material and narrative threads that deviate from what was exactly on the screen in 1967 (including a baffling structural change at a key moment in the story).

The novelization follows the film nearly to the letter - including the footage cut from the film in America - and does so in an incredibly breezy 160 pages. That is just fascinating, to me. If you know the basics of screenwriting, you know that an average script page, from dialogue to direction, constitutes about a minute of film. But most novelizations, by the '70s or '80s, could easily crack the 200-page mark. Even counting the ways a book adaptation of a film can condense visual action sequences, that pacing is brisk. (This is a lesson Quentin Tarantino could have learned when turning his last film, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, into a bloated paperback adaptation that would never have been printed in 1969, when the picture was set.)

Like many novelizations of its era, likely unaware of how the dialogue plays out onscreen, the lines here are looser and more abstract than the final cut, but you never lose the plot between two deliberate gunslingers and one messy bandit. Tuco's wide range of insults on film is even wider on the page, from "son of a saloon tramp" and "miserable seller of souls" to "you polecat's brother" and, perhaps my favorite: "bastard offspring of a thousand bastards."

Descriptive text is minimal - perhaps audiences were familiar enough with Westerns at the time, and this streamlining keeps the book short, after all - but what we do get sets up the characters in our mind just like they are in the film. Angel Eyes possesses a "wedge-shaped face...the color of old saddle leather" and "high cheekbones setting off eyes of palest brown," and possesses the same cross-draw revolver with an extended barrel that you see onscreen. Tuco gets little physical description in introduction, but the immediate detail that "he yearned to be notorious as Tuco the Terrible" is suitable enough.

As for The Man with No Name, he's exactly as we know him: "tall - inches above six feet - lean and hungry...A stubby Mexican cigarro jutted from a corner of his wide, unsmiling mouth...Except for narrowed, glittering eyes, there was nothing sinister about his appearance but Tuco felt a sudden coldness brush his spine." (Eastwood's character gradually acquires in this film the iconic duds he wears in the other two Dollars films, effectively making this a prequel; he does so here, albeit earlier. Angel Eyes gives him the poncho when the pair leave a prison camp, rather perplexingly explaining that "you, your Mexican cigarros and your poncho are becoming a legend." The lack of exact continuity is almost too refreshing to be confusing.)

The cutting room floor: Everything excised from initial U.S. prints is included in the novelization. (Much of that footage was reinstated for a 2004 DVD release; the extra footage can be determined by the English dubbing from a clearly older Eastwood and Wallach - and a stand-in for Van Cleef, who died in 1989 - which had never been done for the scenes in the '60s.) They're mostly small character and transitional moments. Tuco reunites with the gang that attempts to capture The Man with No Name in a hotel. Angel Eyes' search for the gold takes him to a bombed-out Confederate camp. Tuco's mid-film capture and torture of the The Man with No Name in the desert is longer, and is punctuated by a scene where - once he knows that our hero knows where the gold is buried - he attempts to get him aid at another Confederate camp, only to discover the monastery where his brother lives isn't far away. Perhaps most notable is a toned-down version of The Man with No Name joining up with Angel Eyes and his gang after escaping from the prisoner camp; here, the gunslinger doesn't shoot any intruders, but makes the same observation that the assembled men, who total six, are "the perfect number" - one for every bullet in his gun.

What's in a name? We sadly don't know how Millard put the novelization together - but he was likely shown a shooting script, which not only accounts for the copious deleted scenes but also the names of the characters changing a bit, too. While Tuco Benedicto Pacífico Juan María Ramírez keeps his lengthy appellation, Angel Eyes is known here as Sentenza, the name he was given in the Italian version of the film. (In the script, he was apparently "Banjo.") And The Man with No Name, called "Blondie" throughout this film for his fair complexion, is on the page known as "Whitey" for similar reasons. (Millard often calls him "The Man with No Name," "The Man from Nowhere," "the hunter" or "the gunslinger," the latter two of which can be confusing when you consider that everyone in the book is a hunter or gunslinger.)

Bookends: There are two big structural changes in The Good, The Bad and The Ugly's novelization at the beginning and end of the story. An opening chapter does some showing/telling of how the $200,000 worth of gold ended up buried in Sad Hill Cemetery, with Confederate soldiers Jackson (later known as Bill Carson), Baker and "a swarthy Texican named Mondrega" - not "Stevens" as in the film - ambushed by a Union platoon as they transport the gold to commanding officers. (Jackson/Carson is the one who buries the gold, with the others fading in and out of consciousness as the theft is done.

The biggest, strangest deviation in the novel concerns the climactic moments when our three leads reconvene upon the buried gold. Bizarrely, rather than engage in the iconic three-way stand-off among the graves, the gunfight is solely between The Man with No Name and Sentenza. Tuco is sidelined just before this: he attempts to double-cross his on-again, off-again conspirator when both men find the grave they're looking for - and here Tuco finds out his gun was relieved of bullets instead of during that standoff. I have no idea if it ever came to pass that a two-way fight would become a triumvirate before Leone yelled "Azione," though I don't suspect Millard would have pulled such an idea out of nowhere. Still, those close-ups of the actors' eyes wouldn't have hit as hard if Tuco was only a confirmed bystander.

The last word: Confusing finale blocking aside, such a brisk and arresting adaptation of a Western classic offers just the kind of satisfaction you want from a novelization, especially a vintage one. To paraphrase one of Tuco's more memorable lines: when you have to shoot, shoot - don't talk. This book follows that lesson well.