Hollywood & Spine Archive: Phone Home

An overview of the novelization to E.T. THE EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL, originally published in July 2020.

Why yes, it is time again to reminisce about another E.T. writing. I've got good reason to do so: I recently taped an episode of the Sleepless Cinematic Podcast where I went deep on the film and its impact. It may be the best discussion of the film I've ever been part of - and if you're reading this because of it, then hello! I am always like this. E.T. makes for a wild novelization, though not as wild as the next William Kotzwinkle E.T. book. But it is the kind of quintessential stuff that keeps us - or at least me - coming back to novelizations as an art form. (Originally published 7/20/2020)

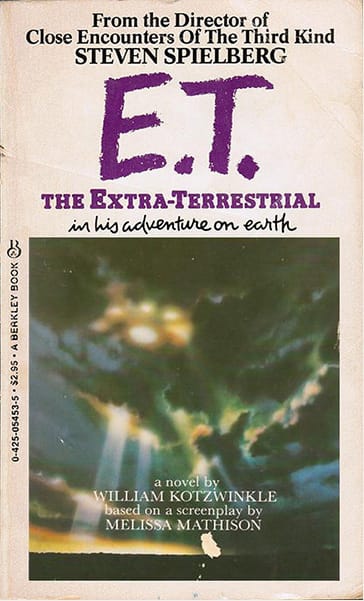

E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial in His Adventure on Earth by William Kotzwinkle (based on the screenplay by Melissa Mathison) (Berkeley, 1982)

The pitch: One of the most popular movies of the last 40 years, this Steven Spielberg-directed classic features a space creature forming a deep, emotional connection with a 10-year-old boy who helps his new friend return to his home planet.

The author: A writer of mischievous, idiosyncratic fantasy novels, William Kotzwinkle's most notable works at the time included 1974's The Fan Man (a personal favorite of Spielberg's) and 1976's Doctor Rat, a winner of a World Fantasy Award for Best Novel. This was Kotzwinkle's first novelization; he'd later pen adaptations of Superman III and A Nightmare on Elm Street 4: The Dream Master.

The lowdown: Is it too much to offer the novelization of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial - as readers may know, my favorite film of all time - as a classic case of understanding why turning movies into books is so fascinating? Biases notwithstanding, I think it's fair. E.T.'s unprecedented success as a film lifted William Kotzwinkle's book to incredible heights (one of the best-selling paperbacks of the year). And thanks to the author's desire to fill in spaces left emptier on screen and his use of a much earlier draft of Melissa Mathison's screenplay, it's easy to point at the E.T. book and say "Here is a good example of turning a movie you watch into something you read."

The film's incredible special effects aside, the magic of E.T. lies with its human, mostly juvenile cast: Henry Thomas as Elliott, the boy who discovers the alien in his backyard; Robert MacNaughton as his older brother Michael, and a then-unknown Drew Barrymore as their younger sister Gertie. Their connection to a made-up alien - the real, believable feelings they convey throughout - keeps E.T.'s viewers hooked. As always, this begs the question: how do you serve an audience as a writer who has yet to experience those performances?

Kotzwinkle answers this by busying himself with the title character, one of the few civilians who got to experience E.T. well before the world did. "Steven took me down a hallway, through a door, into an office and then a closet," the author recalled in People. "He pulled out this box that was so wrapped in tape that I had to use my jackknife to open it. Finally, Steven opens the box and I'm looking at this rubber geek and I'm shaking his hands. It was a rare moment. I'm thinking to myself, 'One of us is nuts.'" He spent five months adapting the story, far longer than principal photography took.

Interestingly, Kotzwinkle is less interested in sci-fi detail than you'd think. We do find out certain trivial tidbits about E.T.: his age (a youthful 10 million years old), the species' attraction/repulsion to Earth life ("peeking in windows" is a sacrilege for these space botanists), and even a little bit here and there about his physiology. (Those three-toed feet are meant for an unnamed planet where life forms do more paddling than waddling, and that roly-poly form is dignified on that world compared to the hideous, stretched out frame of Earthlings.)

But the real flavor of the book lies with Kotzwinkle's decision to offer E.T.'s thoughts on the page. The way the spaceman evolves with his earthly protectors in the book brilliantly parallels the viewer's relationship to E.T. in the film. What starts out with bafflement, maybe even fear and revulsion (that was certainly the case upon my first viewing, and I'm sure many others' as well), gradually melts away to acceptance and eventually affection for a creature that is unlike you in many ways. In the book, Kotzwinkle's E.T. goes as far to describe Elliott as "dumber than a cucumber" early on - he's much more interested in another family member, as I'll explain later - but that apprehension gradually melts away, replaced with simple understanding then true, earnest affection. (Don't forget: for fully half the movie, E.T. communicates in murmured noise before learning to say maybe a dozen words.)

The author's prose choices and details are idiosyncratic, hammering unusual personality traits out of the screenplay (here, the children's mother Mary copes with her divorce through exaggerated self-care, from snacking to skin care) or trying to top different ways to describe E.T. himself ("the elderly voyager," "the old monster," "the ancient pilgrim from the stars"). But he finds beauty in describing one of the most metaphysical details of the film: the unspoken cosmic bond between E.T. and Elliott. (One exchange in the film between a concerned, faceless scientist and Michael summarizes it perfectly: "Elliott thinks its thoughts?" "No, Elliott feels his feelings." The emphasis is mine.)

That connection is first clearly read in the book from Elliott's perspective, when his new alien friend somehow makes him "feel so sad all of a sudden" while he's introducing E.T. to Earth life. Gradually, beautifully, it's further explained as part of an extra-terrestrial's deeper connection to cosmic truths that maybe humans aren't capable of understanding. That spiritual description extends when E.T. gets sick and eventually, briefly, dies: the implied cause of death is universal ennui personified as an unquenchable dragon. E.T.'s last, selfless act in life is to willfully break his connection to Elliott, to spare him the same fate. (Not three pages later, E.T. heals himself - "he did not know how" - which I wish could have been drawn out for larger emotional impact, a common issue in adapting scenes in novelizations largely devoid of dialogue.)

Some passages lack in the wonderment that Spielberg so brilliantly coaxed from Mathison's script: some dialogue is exactly as it appeared in the final cut, others far coarser in their initial execution. The book also undervalues the empathy the only featured adults are capable of in the movie, notably Dee Wallace's aloof but sincere mother Mary and Peter Coyote's "Keys," a scary, unseen governmental bogeyman turned yearning, empathetic link between what Elliott knows of higher intelligence and the rest of the world tries to uncover. Seeing them painted as jerks or bozos - at least one scientist is so put off by E.T. that they wish the creature dead - draws a clear line in the sand as to whose side we're on, but a story so rooted in empathy doesn't need this sort of acidity.

But even if the E.T. novel takes a different route than its celluloid counterpart, it still accurately conveys the relatable themes and values that made the film such a cultural phenomenon. As we've seen before, it's not always easy for a book to do that!

The cutting room floor: The E.T. novelization features two unused subplots and one structural change that a casual fan of the film might find very disorienting on the page. First: there is an extra character in the book - a nerdy classmate of Elliott's named Lance, who is just certain that Elliott is hiding a spaceman from the public and wants in on the discovery. He meets E.T. twice - once unknowingly on Halloween night, and once after weaseling his way into Elliott's house. He ultimately redeems himself by the story's end, accompanying Mary and Gertie to the final rendezvous with E.T.'s spaceship and lying to the police as to where Elliott is headed with E.T. and a crew of bicycling friends. (Fun fact: when the role was going to make it into the film, Spielberg was ready to cast an unknown named Corey Feldman; when the character was excised, the director found room for him in the cast of Gremlins, which he executive produced.)

Second, and arguably weirder: E.T. possesses a strong attraction to Elliott's mother, whom he (and Kotzwinkle) dubs the "willow-creature." His attempts at romantic overtures are frequently waylaid, and the only place this attraction survived on film was in an unreleased deleted scene where E.T. gifts a sleeping (and perplexingly topless) Dee Wallace with a handful of Reese's Pieces. (True to the original screenplay, Kotzwinkle has the alien munching on M&M's, a brand that famously refused to allow their candy to be seen in the film.)

A crucial shift in the story involves the time that elapses in the story, much longer than the final film. And so, E.T. takes two days, not one, to discover Earth life on his own in the house. The first day finds him conceiving the communicator to contact his spaceship, which inspires a telepathically linked Elliott to draw complex circuitry all over his science class. (A version of this scene was filmed but unused, involving a school nurse portrayed by Mathison.) The second day takes place a week or so after the communicator is set up, leaving E.T. to get drunk and lead Elliott on his mind-melded disruption of frog dissection day.

This sets up two additional unused scenes: E.T. drunkenly heals the victims of a mining collapse on the TV news with his magic finger (at one point, a screenplay draft had him saving Dallas' J.R. Ewing before it was wisely scrapped), and Elliott's frog-freeing behavior gets him sent to the principal's office, where E.T.'s shared brainwaves float the boy to the ceiling. (This scene was filmed, arguably the most famous unused sequence in the picture, thanks to an uncredited, barely seen Harrison Ford playing the headmaster.)

Another notable deleted scene from the book that made it into production is an extension of Elliott's sick day with E.T., that culminates in the alien submerging himself in a bathtub. (It was reinstated into the ill-fated 20th anniversary edition</a> of the movie - you know, the one with the walkie-talkies?) A final bizarre detail worth mentioning, ostensibly deleted by the time the film was cast, concerned Elliott and Michael's friends all having strange physical or sartorial choices. Tyler, played in the film by an unknown C. Thomas Howell, was inordinately, self-consciously tall; Steve was prone to wearing a hat with long ears he wiggled as some sort of greeting; and Greg, Mr. "can't he just beam up" himself, recklessly drooled!

The last word: You're probably going to expect a glowing review of an E.T. product if my name's on the byline (well, not everything), but Kotzwinkle's book really is a satisfying archetype of the novelization genre - and even considering the massive success of the material to begin with, that's no mean feat.