Hollywood & Spine Archive: Save Ferris

An overview of the novelization to FERRIS BUELLER'S DAY OFF, originally published in May 2020.

Like some Hollywood & Spine entries from 2020 - written during quarantine - I'm not sure how "good" this is, but I do find some novelty in how the written/prose experience of the movie made it easy to see what many people who don't have fond memories of repeatedly watching this in the break room of a retail job think about this movie. Ultimately, it's didn't change my enjoyment of the film that much; I still think he's a righteous dude. But I certainly get the criticism! (originally published 5/6/2020)

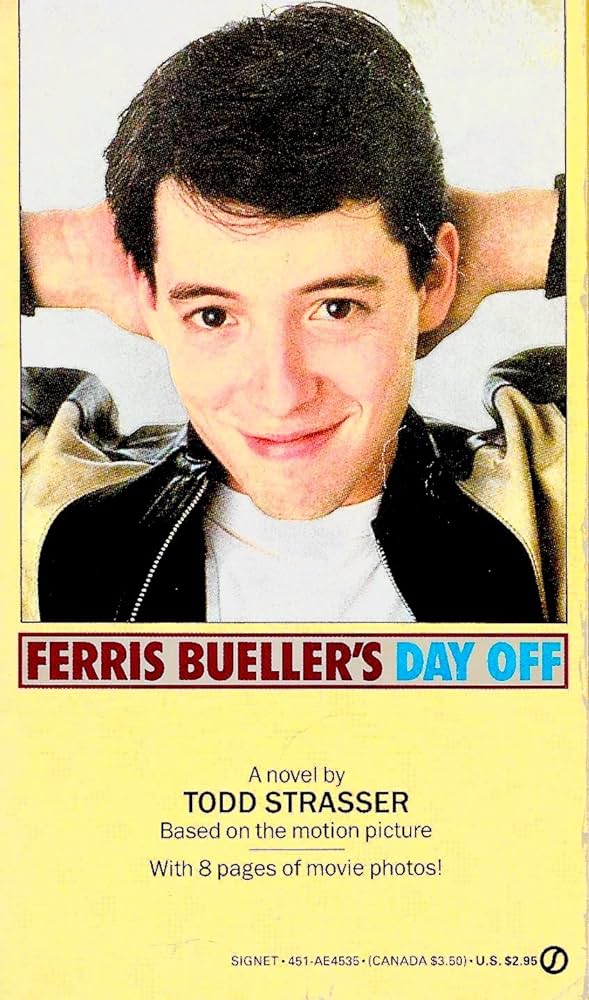

Ferris Bueller's Day Off by Todd Strasser (based on the motion picture written and directed by John Hughes) (Signet, 1986)

The pitch: A maniacally lucky Chicago teen cuts school in the most excessive ways possible, bringing along his friends and staying steps ahead of any adult in his path.

The author: A prolific, award-winning young-adult author - his book How I Created My Perfect Prom Date was turned into the film Drive Me Crazy in 1999 - Todd Strasser has a handful of novelizations in his bibliography, including adaptations of several Macaulay Culkin films (the first two Home Alone films, The Pagemaster, and The Good Son, the one where he's evil and dies at the end).

The lowdown: There are two ways to surprise me when reading a novelization: change my expectations of what the book adaptation is going to contain, and change my perception on the film you're adapting. The novelization of Ferris Bueller's Day Off achieves both before the first chapter is done.

John Hughes famously wrote Bueller in a week, and as one of the most idiosyncratic writer-directors of his generation, it stands to reason that a novelization of his work would have a lot of raw material to work with, as he often filmed his first draft and had editors refine and discard extraneous story beats and material. One of Ferris' most striking (if brief) omissions turns up in the first two pages of the book: here, the Bueller family has four kids, not two. That's right, Ferris (Matthew Broderick) and his snippy sister Jeanie (Jennifer Grey) have a brother and sister, who appear at the book's beginning and end. (Ten-year-old Kimberly convinces her younger brother Todd that his head is growing abnormally, much to his consternation.)

And yet, the pacing is pretty consistent with the film's introduction: Ferris convinces his doting parents that he's ill (much to Jeanie's frustration) and plots a skip day unlike any other. (Cue the Sigue Sigue Sputnik!) Strasser rather brilliantly incorporates a lot of Ferris' fourth wall-breaking introductory dialogue as omniscient narrative exposition, which adds some funny familiarity as you read. (I sheepishly admit I had no idea how those bits would translate on the page until I got to it and thought, "Oh, obviously.")

But the real trick, for better or worse, of the Bueller book is unintentionally making a lot of postmodern criticism of the film a little clearer. In the heat of the Reagan '80s, it was not unthinkable to present an upper-middle class Chicago suburbanite and his well-off (if emotionally destitute) best friend and girlfriend as heroes, traipsing about and thumbing their noses at the rest of us. (This lines up with the perceived though occasionally challenged description of Hughes as Republican.)

Even then, though - and especially today - it's easy to look at Ferris Bueller and decry it as David Denby did in New York: "a nauseating distillation of the slack, greedy side of Reaganism." Matthew Broderick does deflect some of that criticism with his easy on-screen charm - a bitter irony, considering that he walked away without serious charges in a car crash that killed two people a year after Ferris was released - but in the book, it's not hard to declare Ferris Bueller a grade-A asshole. He steals money from his family to make sure he can bankroll his day off. His transactional relationship with Cameron is underlined by memories of Cameron taking the heat for some of Ferris' most ridiculous pranks. (Can you imagine Cameron Frye, as played by a young Alan Ruck, catching blame for masterminding a repaint of a water tower?) Worst of all, though: side characters make it clear that Ferris can be a bit of a jerk, but Ferris' own thoughts indicate he doesn't understand why folks like his girlfriend Sloane's family don't seem to care for him much.

We've seen the risks of extraneous information from J.K. Rowling diminishing the impact of the Harry Potter stories, or the yards of canon Star Wars fans have to cut through to understand certain revelations about the galaxy far, far away. The Ferris Bueller novelization, of all places, is the first time such a seemingly grounded adaptation changed my perspective on the story. I don't dislike the film, mind you, but now I more clearly see why others might not. Leave it to another medium to carry that different message!

The cutting room floor: Despite the breezy 178-page length of the book, there are quite a few hijinks that were cut from the film but appearing on the page. There are a couple funny recurring jokes, like how most of the people the dimwitted principal Ed Rooney comes into contact with are former students eager to see his cheese left out in the wind by another pupil. A few other snips include:

- A scene where Ferris, Cameron and Sloane attempt to cash a savings bond while avoiding a chance encounter with Ferris' mom. (Mrs. Bueller herself gets an unrealized subplot in the script, following her as she attempts to sell a house to a set of parents and their rowdy son.)

- Several Breakfast Club-esque discussions between Ferris, Cameron and Sloane on love, aging, suicide and even nuclear war (heavy!)

- A different denouement to the sequence at the French restaurant, where the trio are served pancreas (explaining a line that did made it to the film)\

- Extraneous additions to the sequence at Wrigley Field: Ferris gets the foul ball he catches autographed by Anton Rodriquez, the Cubs' short relief man and one of Sloane's favorite players. He accomplishes this by having himself bodily lowered toward the dugout, which is captured on camera and secures him an interview with WLS-AM after the game (the party at the German-American Appreciation Parade occurs in between these moments, and the interview is heard by the rowdy son of the prospective house buyers)

- Perhaps the funniest deleted material that would have paid off nicely onscreen was the saga of Garth Volbeck. Ferris cites him to Cameron as a cautionary tale: an old friend of his driven mad by problems not unlike Cameron's difficult relationship with his family. We don't know what became of him until the end of the story: he's the burnout Jeanie spends some quality time with when she's mistakenly sent to the police station (played memorably in the film by Charlie Sheen).

The last word: Novelizations usually move pretty fast. If you don't stop and consider interesting ones like Ferris Bueller's Day Off, you might miss something.