Hollywood & Spine Archive: Somewhere in My Memory

An overview of the novelizations to HOME ALONE and HOME ALONE 2: LOST IN NEW YORK, originally published in December 2020.

And so we come to the last original Hollywood & Spine published before TinyLetter shut down! I'm honestly not sure where it'll go next, but it was a lot of fun to try writing about something that wasn't music for a change. I hope you enjoy reading or re-reading all of them! (originally published 12/22/2020)

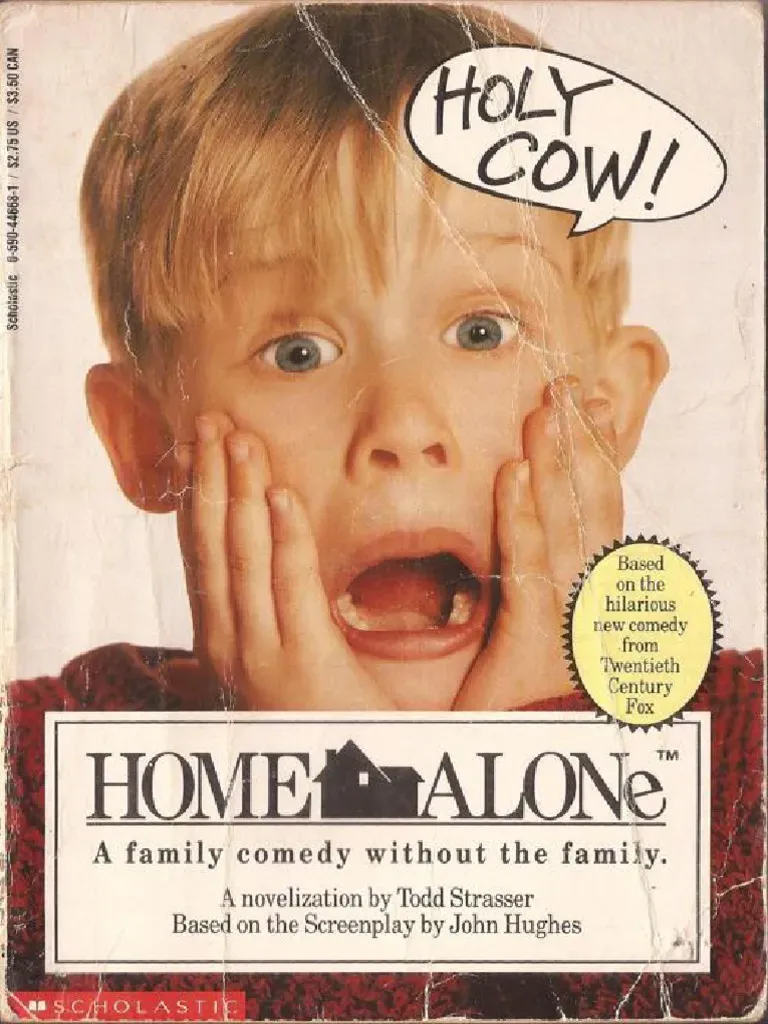

Home Alone and Home Alone 2: Lost in New York by Todd Strasser (based on the screenplays by John Hughes) (Scholastic, 1990/1992) and Home Alone 2: Lost in New York by A.L. Singer (based on the screenplay by John Hughes) (Point/Scholastic, 1992)

The pitch: When a resourceful kid is accidentally left at home by a Chicago family ahead of a Christmas vacation, he does some serious growing up - including thwarting a pair of burglars. Then, because the film was an unexpected success, he does exactly the same thing, except in Manhattan.

The authors: Todd Strasser - a noted young-adult author who wrote the book that became the 1999 film Drive Me Crazy - wrote a few novelizations in his time, including a fascinating adaptation of John Hughes' Ferris Bueller's Day Off. A.L. Singer is a pseudonym for writer Peter Lerangis, a known ghostwriter who contributed to book series like The Baby-Sitters Club and Sweet Valley Twins - plus his own young-readers series Seven Wonders.

The lowdown: Three decades from its original release, Home Alone remains an endlessly entertaining and whimsical film that really captures the Christmas spirit for a generation or two. Writer/producer John Hughes spent the '80s capturing the eccentricities of the American middle-class family, usually through the eyes of teens (Sixteen Candles, The Breakfast Club Pretty in Pink) and sometimes through lovable louts (the National Lampoon's Vacation series, Planes, Trains and Automobiles, Uncle Buck).

Home Alone shared the DNA of Planes, Buck, and Christmas Vacation, putting a child (Buck co-star Macaulay Culkin, a relative unknown) in the middle of the action. The payoff was immense. Released just before Thanksgiving 1990, the film stayed in the domestic box-office top 10 until the following spring. Culkin became a charming superstar and Hughes a kingmaker.

And it's pretty clear the experience may have nearly broken them both.

Culkin's exploits are well-known - check this great Esquire feature from earlier this year - but Hughes' experiences post-Home Alone are perhaps less considered. He wrote four films released in 1991, all comparative flops (including Curly Sue, his first directorial effort since Uncle Buck). They all had elements of that Hughes sweetness and humanity, but none of them had what Home Alone had: 20 minutes of adult actors (including an Oscar winner) get beaten senseless by industrial booby traps.

So, as Hollywood insisted, 1992's Home Alone 2: Lost in New York was an uninspired beat-for-beat copy of the original that also scored at the box office. From then on, nearly all of his scripts - including adaptations of Dennis the Menace, 101 Dalmatians, and an unrelated-to-the-first-two Home Alone 3 - featured scenes in which humans are Looney Tunes-style obliterated by hardware. By the end of the '90s, Hughes had essentially retreated from Hollywood, and in 2009, he died of a heart attack. His early works are still revered by comedy fans, but even some of the people he made famous have reckoned with some uncomfortable implications of his oeuvre.

Hughes' Home Alone self-ripoffs offer a compelling argument that the slapstick sequences aren't as central to the original film's charm, yet the films wouldn't work without them. That's kind of a problem for the novelizations: describing falling paint cans or nitwits getting covered in paint and varnish is not a lot of fun to experience without seeing them. (Home Alone 2 came with an eight-page color photo spread that cannily hid any evidence of contraptions.) There's not even the facile joys of excessive onomatopoeia - precious few "ooof"s or "thwack"s, which seems obvious enough.

Readers at least do get enough bits of background in Strasser's adaptation of the first film, including a clear-headed explainer of which McCallister kids belong to which families. Most notable, of course, is an answer to that beloved viral question: how did the family acquire such a big house? The solution: Kevin's mother Kate works in fashion and his father, Peter, works in some sort of office gig. (That would also explain the presence of mannequins in the family's basement.)

The Home Alone adaptation does suffer from mild oddities in detail; noting Kevin's age (seven) and hair color (brown) is at odds with the cover photo of the blonde Culkin. Some things are absent entirely, like much of the charm of the McCallister family's third-act helper Gus Polinski (a cameo role that, in fairness, John Candy mostly improvised). But those quibbles are minor, and this slim volume (ostensibly targeted to young and pre-teen readers) does a good job of grasping the homegrown charm of the source material.

The same cannot be said of Home Alone 2, which - befitting its blockbuster status - was bizarrely adapted into two novelizations: one by Strasser and a mass market-sized volume by Singer that clocks in at 223 pages, about 70 pages longer than the other adaptation. (The reading level and price point for each was not terribly different - making two was an odd choice.) And they make for jarring reads, exposing the tackiness of the source material - the Pigeon Lady is a poor substitute for the scary old man from the first movie, which at least had some sort of stakes throughout the picture - and showcasing how absolutely boring certain Home Alone standards are when written out. For instance: there is no trap preparation sequence in the first book, one paragraph in Strasser's second, and five pages' worth in Singer's. Either of them make for the saddest kind of novelizations imaginable - the ones that are more for selling products than reading experiences.

The cutting room floor: For a junior novelization, Home Alone features a decent amount of excised character moments, many of which were filmed. There are some gags (Kevin's odious Uncle Frank makes a rude joke about English speakers in Paris to "yank" his nephew's pants down) and even some tenderness (Kevin's sister Linnie expresses concern for her brother while she and her dad spend a sleepless night in France). The best one, though, might be a biting moment of satire between Harry and Marv - who, it's worth noting, have full names here. (Joe Pesci's diminutive schemer is Harry Lyme(?!) and Daniel Stern's towering goof is Marv Murchens.) In an early, alternate scene, Harry waxes poetic on families traveling abroad for Christmas, decrying "the moral decay of contemporary society" before Marv interrupts with an inquiry on which house to rob first.

Conversely, as Home Alone 2 is a carbon copy of the original, deleted scenes here are few. Both books do feature an interesting alternate opening: a dream sequence where Harry and Marv return to the McCallister house to exact their revenge on Kevin, only to suffer more injuries through booby traps. (One gag, involving a mannequin and an errant lawnmower, was ultimately used in Home Alone 3.)

Otherwise, there's a few small bits that recall the original film, all of which were wisely omitted. Kevin has a wiseass moment with some men in the Plaza Hotel steam room (Strasser's book establishes that the men are nude, a weird detail for a kid's book); the McCallisters mistake Buzz's slack-jawed lust over a scantily-clad Floridian for concern over his missing brother in Miami; Marv gets socked by the pretty blonde an extra time at the toy store thanks to a weird prank involving fake gorilla arms; and - in a sign of real cynicism - Kevin was to repeat the infamous slapping-cheeks-and-screaming bit in New York.

One last weird note for Home Alone 2: Singer's book features an actual trap substitute. Marv loses his facial hair to a roll of hot-glued cheesecloth instead of getting electrocuted so hard he turns into a literal skeleton.

The last word: Ultimately, the Home Alone books are better left alone, with the vibes of the original films remaining somewhere in your memory - until the inevitable Disney+ reboot.