Hollywood & Spine Archive: 'The Rose' in Bloom

An overview of the novelization to THE ROSE, originally published in July 2022.

Do people remember The Rose? Obviously, it was well-received at the time, and was added to The Criterion Collection in 2015, but I don't know that it's a major touchpoint for the average cinephile. (Director Mark Rydell has a lot of other films I can name, in part because quite a few of his films have been scored by John Williams.) I'm not entirely sure if I did a great job of explaining this movie's whole vibe, and for that I apologize - I was obviously, definitely excited about tackling a novelization to a movie steeped in music and how weird that is, conceptually. I also have to shout out my friend Kayleigh Hearn, who sent me this (and several other novelizations) not long after I started the Hollywood & Spine project! She's a great writer and a wonderful friend. (Originally published 8/29/2019)

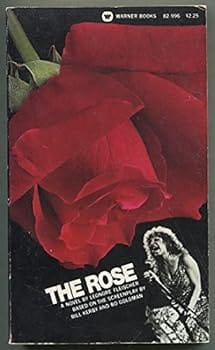

The Rose by Leonore Fleischer (based on the screenplay by Bill Kerby and Bo Goldman) (Warner Books, 1979)

The pitch: The tragic days of a Janis Joplin-esque rock star battling demons that won't go down without a fight. Bette Midler's breakthrough film performance netted her a Golden Globe and established the singer as an actor, as well.

The author: A dependable adapter of films from Ice Castles and Rain Man to Flatliners and even the musical Annie, Leonore Fleischer was prolific enough to earn her own brief feature in People! She also churned out a few serviceable biographies on the likes of Joni Mitchell and Dolly Parton, enhancing her music-biz writing cred for this particular adaptation.

The lowdown: If novelizations are handicapped by capturing a film without its pictures or performances, they can struggle even more when sound is integral to the adapted movie. The most famous example may be the book version of The Bodyguard in 1992, which features Whitney Houston stealing romantic moments with Kevin Costner on the page to David Ruffin's "What Becomes of the Brokenhearted." (That track proved elusive to clear during production, and Houston instead covered Dolly Parton's "I Will Always Love You," still one of history's biggest pop singles.)

If diagetic music is enough of a make-or-break in novelizations, what must we make of writing about fictional, filmed concerts? Can you imagine a Purple Rain novel that covered Prince and The Revolution in detail without actually revealing the songs? This is the hurdle The Rose has to clear in book form. Midler's powerhouse versions of songs like "When a Man Loves a Woman" or "Stay with Me," brilliantly overseen by cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond, aren't grist for the mill of this tome. Instead, Fleischer has to fill those spaces in with very general brush strokes and simple, noncommittal, Janis Joplin-esque touches, like unnamed covers of Ma Rainey songs and other blues standards.

Fleischer wisely makes up for this handicap by offering a vivid world of printed detail about the 1969 rock scene that The Rose inhabits. Where we'd be treated to performances on film, we instead get illustrative passages detailing the backstory of Midler's Rose and her unscrupulous manager Rudge Campbell (played by British thespian Alan Bates).

Both have hardscrabble origin tales. Rudge (born Reginald Callahan) escaped working class London (and the bombing of his family home in World War II, apparently the same day Rose was born) with a dedication to make money at all costs. Rose, desperate for attention from her working parents in rural Florida, found various forms of salvation in sex and music, namely the songs of the black church she snuck into. Her only friend, a deeply closeted young boy named Arthur Pye, is cast out of town after a cross-dressing incident, re-emerging in San Francisco as the Summer of Love coalesced, and inviting The Rose to live her best life. (In the film, Rose has an unnamed drag queen friend, played with panache by legendary disco singer Sylvester.)

Rudge and Rose's paths cross at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, which is pretty bizarre the more you think about it: the book makes it very clear that Big Brother and The Holding Company (who were signed to Columbia Records off the strength of their set) were also in attendance at the festival. Rose's feeling of inferiority to Joplin leads to her first serious encounter with pills and booze before her own performance. The film deals with this much better by having The Rose be a Janis stand-in instead of a contemporary - after all, the film's script was retrofitted from an attempted Joplin biopic, called The Pearl.

It's not the only stumble in the book: Fleischer is obsessed with the generous size of The Rose's breasts. It doesn't feel like we go more than five pages at a time (out of 250) without it coming up. Watching the movie, Midler dons a variety of diaphanous tops that accentuate her figure, but...I don't know. Maybe it's because I was first aware of Bette as the lead in campy or sentimental films like Beaches or Hocus Pocus, the singer of treacle like "From a Distance." She was mom-rock, and thinking of her as an explicit object of desire - especially in a book written by a woman - might come off as a little behind the curve. (This is apparently not the only time Fleischer has written like this, too: the novelization to Bruce Lee's Enter the Dragon, which she wrote under a male pseudonym, features heavy chest chat.) But hey - rock writing was like that, and Fleischer's prose captures the grit of the music business as it probably was some 50 years ago.

The cutting room floor: In addition to the backstories on Rose and Rudge, there's a lot of great color on the page that doesn't end up in the film. After her press conference early in the film, Rose breaks away from Rudge and takes a cab to a seedy hotel, where she has an uncomfortable reunion with Lonnie, an old flame/bandmate heavy into the heroin that Rose managed to kick. (It's very possible this was filmed, based on the blocking seen in this package on NBC's The Today Show.)

Additional heartbreaking asides include the revelation that Sarah Willingham (Rose's old lover who unwittingly causes a rift between her and protective male partner Houston Dyer) was specifically called by Rudge to stir up trouble; later on, during her depressing return to Florida, Rose visits an auto dealership owned by the boy who gave her her first kiss, buys a Ferrari in cash and smashes it with a tire iron on the spot.

Finally, it's of note that the only song explicitly mentioned in both the song and the film is "Fire Down Below," which not only didn't make the soundtrack album but is humorously incongruous, as Bob Seger hadn't written it until long after the film's late-'60s setting.

The last word: The prose is a little rough in places, but this is a great example of a novelization that knows how to work around what an author will have a hard time to write.