Hollywood & Spine Archive: Where Do I Begin?

An overview of the novelization to LOVE STORY, originally published in August 2020.

If there's a studied, manic energy to Hollywood & Spine in the late summer of 2020, it wasn't COVID lockdown mania: I had been laid off from a job I'd held down for about eight years. Scary any time; doubly so in the middle of a global pandemic. Nonetheless - or perhaps unsurprisingly - I was happy to overanalyze this book and this film, which are both, in my opinion, astoundingly bad. I still gave 'em a fair shake, though! That's the magic of Hollywood & Spine, baby. (originally published 8/11/2020)

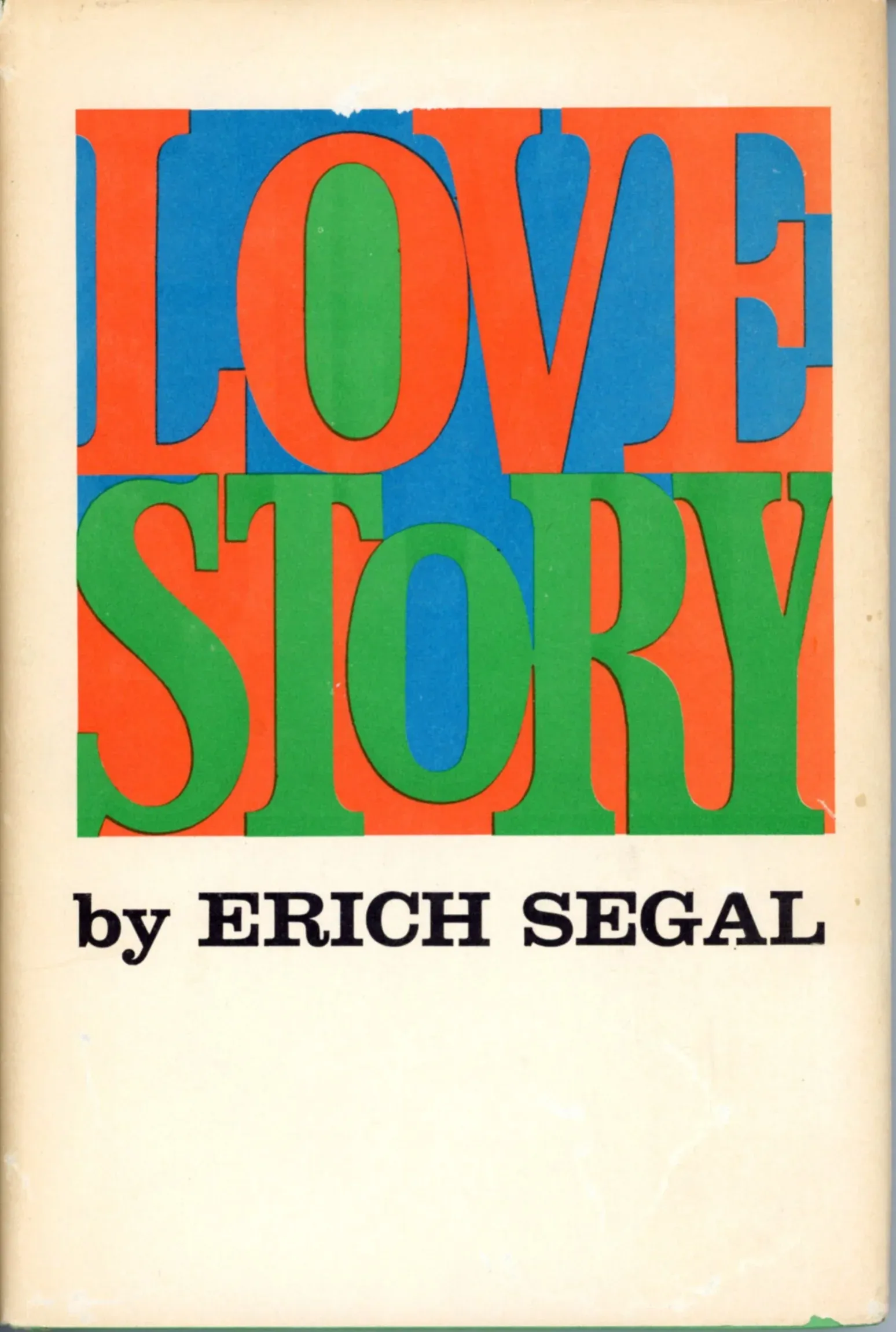

Love Story by Erich Segal (based on his screenplay) (Harper & Row, 1970)

The pitch: A deeply goopy tale of an upper-class Ivy Leaguer and his romance with a working-class student that's put to the ultimate test.

The author: A most unusual public figure, Erich Segal (1937-2010) was a scholar of Latin and Greek literature at Harvard (his alma mater) and Yale, but really wanted to write scripts. At the time, his most famous credit in that field was being one of four writers on The Beatles' animated feature Yellow Submarine.

The creation: On April 9, 1969, amid a peaceful occupation of student demonstrators at Harvard University, Cambridge mayor Walter Sullivan called in hundreds of cops to break up the protests, a move roundly criticized by even the chief of the university's police detail. Negative reaction to the police presence - a tragically familiar concept to anyone drawing breath in 2020 - actually led to some of the protestors' demands for reform being met, including the rescinding of privileges held by the campus ROTC program and the allowance of student voices in helping shape the curriculum of the then-new African-American studies program.

Less than a year later, Harvard was on the map yet again, thanks to a movie where two mismatched students, one comically rich and one stereotypically working-class, fall in love on the campus and then - spoilers for a 50-year-old tale - one of them dies of cancer in the most elegant way possible.

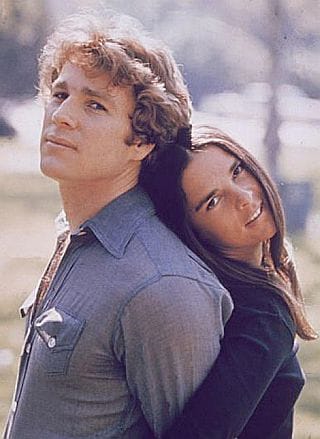

The genesis of Love Story - 1970's best-selling book turned brisk drama that became 1971's top-grossing film - is truly fascinating. You might question why it's part of the Hollywood & Spine canon: the book was released on Valentine's Day, broke publication records by the time it became a paperback in the fall, and released to theaters that Christmas, featuring Ryan O'Neal and Ali McGraw as the mismatched lovers who never have to say they're sorry. Seems like a pretty standard book-to-film pipeline, no? The truth is actually a little more complicated.

Erich Segal was driven to entertain. At Harvard, he co-wrote the musical Sing, Muse! with a student named Joe Raposo; it opened off-Broadway in 1961 to mixed reviews. (Raposo later found his voice writing songs for the youth of the world.) Even his first academic book was a bit of a Hollywood clout-chaser: 1968's Roman Laughter assessed the work of Roman playwright Plautus, immortalized two years earlier in the film version of Stephen Sondheim's A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum.

Seemingly oblivious to the counterculture on his beloved campus - or, perhaps, looking to transcend it entirely - Segal came up with a wispy tale of a young Harvard man so devoted to a smart-talking Radcliffe student that he rejects his life of privilege to stand by her 'til the very end - which, of course, comes quickly and tragically. His screenplay was soundly rejected by most studios until a persistent agent at William Morris convinced Paramount Pictures to take a chance on it. (It didn't hurt that Segal had a friend and fan in Ali McGraw, wife to the studio's iconoclastic head of production, Robert Evans. That agent, Howard G. Minsky, became the film's producer.)

Paramount's caveat: Segal would have to adapt his script into a book to prime the pump for the film. And prime it did: Love Story was treasured by women yearning for entertainment that presented love and romance (prominent working woman Barbara Walters was an early fan) even as it was pilloried by the critical establishment (members of the National Book Award threatened to resign if it was so much as shortlisted for a prize). Savage reviews aside, it's hard to argue with an initial paperback order of four million copies - an unheard of number at the time.

The execution: Five decades later, 1970 as a whole looks both very similar and freakishly different to how things are today: unpopular military action, police brutality, rampant racism and a deeply corrupt president. (All that's missing is the global health crisis.) The want of entertainment that can reach across the aisle and activate multiple types of people's pleasure centers - think superhero movies today, I guess - makes perfect sense in fractured times.

So it's worth revisiting Love Story, a book that roughly one out of every four Americans read and people flocked in droves to see in pre-multiplex times - and asking one simple question: what the fuck was everyone thinking?

As a book whose latest pressing (with new forewords and afterwards penned for its 50th anniversary) clears about 140 pages, Love Story may be one of the most mirthless quickie novels of its time. Narrated from protagonist Oliver Barrett IV's blasé point of view - he's sure happy to reject his family's wealth and privilege, but huffs when asked to consider why - we tumble headfirst into his romance with quick-witted Jenny Cavilleri. Within a fistful of pages, they go from negging each other ("bitch" is a disturbingly frequent term of endearment in Segal's world) to slavish devotion. Oliver and Jenny are each other's world, to the point where almost no other characters exist. (The ones who do are almost exclusively men, from Ray Milland as Oliver's stiff upper-crust father to one of Oliver's roommates, played by an actual Harvard grad credited in his first motion picture as Tom Lee Jones.)

The details on the page are scant: in the film, emotions are rendered through wordless, endless montages and Francis Lai's haunting theme. Without the callow affability of Ryan O'Neal and Ali McGraw's faces and slightly campy performances, it's not clear to this modern-day reader what the big deal was. What rises to the top from the ephemeral, waste-no-time story, in either the book or the film, is a mishmash of gee-ain't-my-alma-mater-great nonsense and clinical, often boorish depiction of romance. For something that was so loved by female readers, it's wild to see tension introduced by Oliver harshly rebuffing his beloved for trying to build a bridge between her husband and his estranged father, or - and I hope you're sitting down for this - Jenny's doctor divulging her fatal illness to Oliver only, suggesting he break the news to her as gently as he can.

If any further anecdotes to the weakness of Love Story's source material are needed, here are two. First, the film's most iconic line - "Love means never having to say you're sorry" - was an accident, rendered on the page as "Love means not ever..." but thankfully bungled during filming. Second, Segal's celebrity status, which led to appearances on late-night television shows and self-important signings to throngs of fans, ultimately cost him a tenure track at Yale. Gaining pulp and losing a plum...where do I begin?

The cutting room floor: Thanks to its abbreviated pace - the book takes about as long to read as the film does to watch - there are no major deviations between the two, save for some stray dialogue and offhand, expendable details.

The last word: Just...listen to Andy Williams instead, alright?