Hollywood & Spine: Tooned In

A book based on a movie based on a book that needs a little more animation.

Wow! For the first time in several years, a new Hollywood & Spine entry—my 2019-2023 newsletter about the art and craft of movie novelizations. This one covers a truly unusual adaptation of a blockbuster movie already based on a book, which is oddly straightforward in some ways and not so much in others.

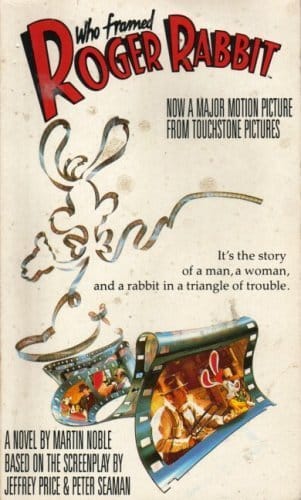

Who Framed Roger Rabbit by Martin Noble (based on the screenplay by Jeffrey Price & Peter Seaman [itself based on the novel Who Censored Roger Rabbit? by Gary K. Wolf]) (Star (U.K.), 1988)

The pitch: A hard-luck detective gets into some animated situations when a comedic cartoon character is accused of murdering a human in post-WWII Hollywood.

The author: A career novelizer in England, Martin Noble penned prose adaptations of U.K. fare like the BBC dramedy miniseries Private Schulz and the World War I farce Bullshot before writing adaptations of cult TV shows (Automan, Cover Up) and films (Ruthless People).

The lowdown:

If you haven't been to Toontown, maybe I can describe it to you like this. Imagine you're in bed. It's a pitch dark night and though your eyes are open you can't see a thing. You lie there and you're not sure whether you're awake or asleep. Then suddenly you think, I must be asleep 'cause otherwise why am I dreaming in Technicolor and not just Technicolor but cartoon color? You're inside a cartoon landscape where there are no greys, no shades, no soft edges. You're inside an animated movie and that's Toontown. And there's one other thing: in Hollywood, the Toons have to do what the humans tell them, but in Toontown the Toons make up the laws of nature as they go along.

This is how Martin Noble describes the Toon world of Who Framed Roger Rabbit as grizzled detective Eddie Valiant makes his way back there in the second half of the film. It's a dizzying journey for him—going back to a place he used to love until tragic circumstances made him swear Toons off—and us, having just seen new and vintage cartoons interacting with the real world in ways thought impossible on screen. Noble is, in some ways, also making up the laws of nature as he goes along. After all, he's adapting a film itself based on a book that didn't even have a Toontown to speak of.

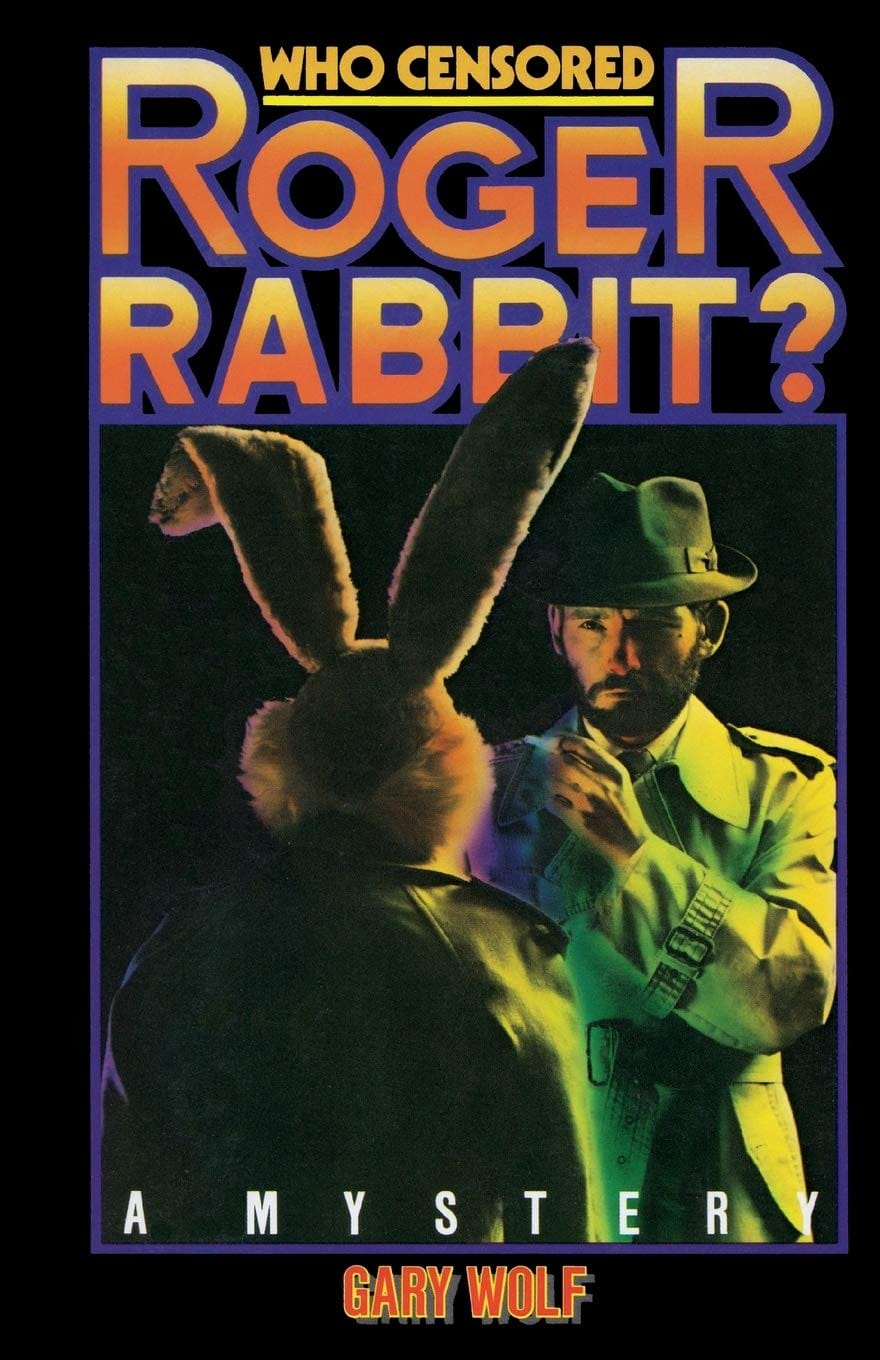

If you've not read Gary K. Wolf's 1981 novel Who Censored Roger Rabbit? (and I suspect many of you have not), it's kind of a miracle the book became any movie, let alone the one we know and love today. The original story involved a present-day detective solving the murder of one Roger Rabbit, a sidekick in a newspaper comic strip whose innocence isn't so black and white. You read that right: Roger is a comic strip character, who emits speech bubbles when he speaks that sail at your head or sprout sharp edges depending on his emotions. Jessica Rabbit and Baby Herman are supporting characters, but there's no period setting, no Disney or Looney Tunes characters making cameos, the sorts of things that made the film really singular.

Who Framed Roger Rabbit, as we know it, is one of the major products of Steven Spielberg's imperial period. Though his post-E.T. '80s involved a lot of experimenting with more "mature" films as a director like The Color Purple or Empire of the Sun, it was also the era he set up a shingle with producing partners Kathleen Kennedy and Frank Marshall through Amblin Entertainment, who'd help craft a series of memorable blockbusters like Gremlins, the Back to the Future trilogy and The Goonies. Roger Rabbit utilized a lot of the creative and technical teams behind BTTF, including director Robert Zemeckis, composer Alan Silvestri, editor Arthur Schmidt and cinematographer Dean Cundey. Much of the creative footwork, though, began with screenwriters Jeffrey Price and Peter S. Seaman, who adapted Who Censored Roger Rabbit? into a much likelier hit—essentially, a take on Chinatown with cartoons in it—and ended with Spielberg's influence as a producer, convincing Warner Bros., Universal and other animation rights holders to create an Avengers-style crossover of cels and paintbrushes. (In the middle was Oscar-winning animation director Richard Williams, bringing the Toons to life in real-world situations, interacting with real props and sets and moving through shadows and lights as the camera moved dynamically. One cannot omit the work of stars like Bob Hoskins as Valiant, who did such a good job interacting with invisible co-stars that he reportedly dealt with hallucinations after the cameras stopped rolling.)

We've seen how novelizations of Spielberg productions like Gremlins or Back to the Future—both written by the late George Gipe—can read like funhouse mirror versions of the familiar films thanks to a distinct, occasionally overwhelming authorial voice. Who Framed Roger Rabbit, a novelization that was only issued outside America (complete with British spellings), almost suffers from the opposite problem. Noble, who almost certainly wrote the novelization after seeing the film (which came out in British cinemas six months after premiering domestically; the book is front-loaded with praise from U.S. reviews), seems like he's transcribing. It's written mostly from Valiant's first person perspective, with some omniscient switches for events that he's not directly participating in, like the short cartoon being filmed in the opening scenes. So focused is he getting details and dialogue exact that he neither injects the proceedings with any sort of fun tone—think Raymond Chandler for the blockbuster set—or even a sense of bewildered zaniness that cartoons are interacting with flesh and blood.

If anything, Who Framed Roger Rabbit as a book is most interesting based on things Noble inexplicably gets wrong. Early on, he miscounts the amount of animated weasels doing Judge Doom (Christopher Lloyd)'s bidding, and depending on what scene he's writing, they don't always seem to be in the same scenes. (For those keeping track at home, there's Smart Ass, the white-suited leader; Greasy, the green-suited sleaze; Psycho, wearing a straight jacket; Wheezy, constantly smoking; and Stupid, the oaf in a propeller hat. The original plan was to have seven, in a coy flip on Snow White.) The most unusual omission, however, is that the murder victim who drives the plot, Toontown mogul Marvin Acme, is never once mentioned by full name. That's right: the word "Acme" isn't written once in nearly 200 pages. He's "Marvin the Gag King," at most. Was there some sort of legal stipulation against using the name in England? Research proved inconclusive, but I'd hate to see Coyote vs. you-know-what get held up by another ridiculous circumstance.

The cutting room floor: As an extended stenography session, the Roger Rabbit novelization offers nothing that wasn't in the final cut. This is particularly frustrating, considering the book's several photo spreads (at least two black and white and one in color) offer glimpses of the film's major deleted scene. Originally, Valiant's detective work would take him back to the Ink and Paint Club to search for Marvin Acme's missing will. While there, he'd get apprehended by Judge Doom and the weasels, who—with Jessica Rabbit watching—would take him to "downtown Toontown," where a cartoon pig's visage is superimposed over his head. (Valiant removes the offending animation with a bottle of turpentine in the shower, which is why he's shirtless when Jessica approaches him in his office. Ironically, the excised animation was the first completed for the film.) A novelization would have also been an ideal spot to see the ultimately unfilmed sequence involving Acme's funeral, proposed to feature more classic Toons including Tom and Jerry, Popeye and Casper the Friendly Ghost.

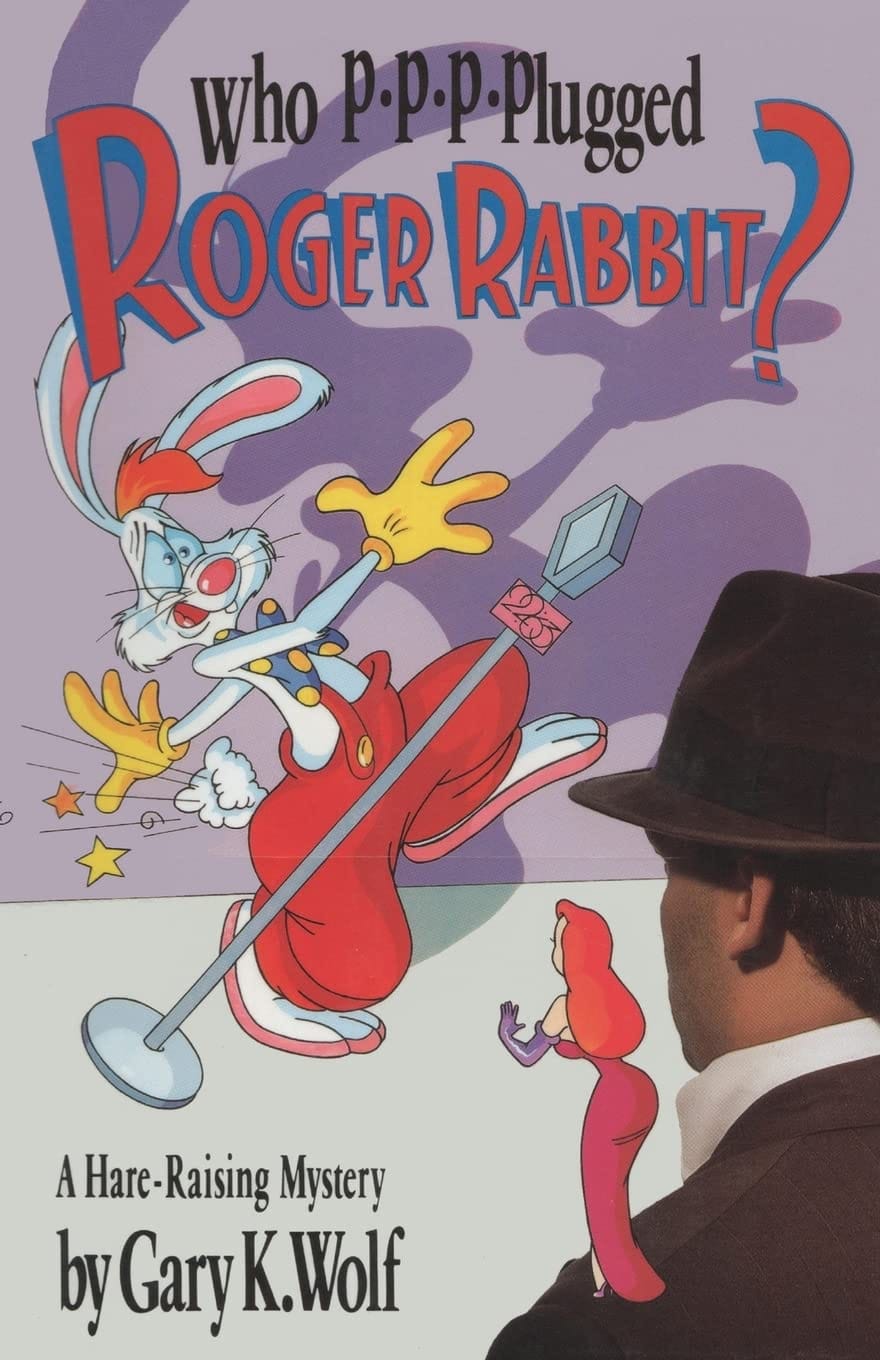

The last word: Perhaps Roger Rabbit really is one of those stories that's meant to be seen instead of read. (Or maybe even just heard; I've always loved this "storyteller" album that retains more of the hardboiled tone.) Even Gary K. Wolf had this problem: 1991 saw the publication of a bizarre novel, Who P-P-P-Plugged Roger Rabbit, a continuity-shredding follow-up that attempts to square the original book and the film. The action was set against a proposed Toon-assisted adaptation of Gone with the Wind which finds Roger competing for a part opposite Clark Gable. After another series of murders, the production ultimately eschews Toons altogether, ignoring the fact that the actual film was released nearly a decade before the events of Who Framed Roger Rabbit. Then again, this is a book where Valiant falls in love with Jessica's identical but pocket-sized twin sister.

Wolf later sued Disney for unpaid royalties, and the dual challenges of wrangling Spielberg for additional projects and drawing interest in hand-drawn animation instead of computer graphics sadly relegated Roger to Disney's dustbin. But we'll always have Toontown in our memories.