Music's Physical Crisis is Taking Notes

Why is it this hard to get a full album, with liner notes, on a disc?

Last weekend, one of the world's most famous pop stars stopped time and broke the Internet anew with the release of a new, bold artistic statement. It was a thoughtful referendum on country and Americana music, race, tradition, songwriting interpretation and the value of speaking about such things through music, filtered through the thoughts of social media users and the media critics who dare to face a terrible, uneven landscape to run thoughtful reviews.

But don't try to get the album in full on a physical format.

"Ya Ya," one of Cowboy Carter's standout tracks, is one of several not available on physical editions of the album.

Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter has made waves since its release last Friday, including more than 76 million streams of its 27 tracks in its first 24 hours on Spotify - handily the biggest single-day total of 2024 thus far. But five of those tracks have been excised from vinyl copies on the singer's web store. (Four of those tracks are missing from CD versions, too: the promise of an "additional song" on that format turns out to have been the inclusion of album track "Flamenco." Neither of these physical listings offered a published track list.) Additionally, Rolling Stone reports that the liner notes and album credits - whose absences and partial presences were subject to social media scrutiny - aren't in the physical copies either, instead accessible via QR code. (Did you even know streaming services offered credits? They don't do much of a job of letting you know, perhaps in part because such credits have never seemed more malleable.)

Whoever I say wouldn’t be credited apparently https://t.co/eBIfWYrXfN

— Hannah Jocelyn 🫡 (@hannahjocelync) April 1, 2024

No official reason has been given for the discrepancy, although fans and journalists have been quick to speculate that the ever-evolving album had some down to the wire updates, from title to how many tracks were on it in the first place. But the concept of a partial physical album is nothing new. Nicki Minaj's Pink Friday 2 and Ariana Grande's Eternal Sunshine each had pressing discrepancies. Taylor Swift, who released a digital deluxe edition of Midnights three hours after its release in 2022, and released other versions with more music in the months after, will release her new album The Tortured Poets Department this month; four different CD pressings made available through her web store will feature a different bonus track. (I'd say it's a safe bet that a fifth edition will include all those tracks plus something extra before the album cycle - excuse me, era - is done.)

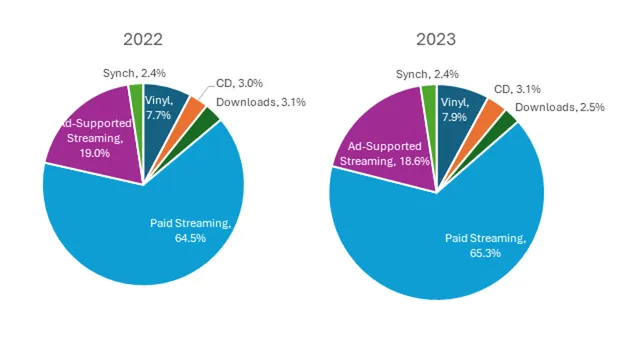

So it goes for the increasingly scarce physical music consumer - the types of people who took John Waters' comments about books way too seriously, instead about vinyl or CDs. But they're a vocal minority: the most recent RIAA data places vinyl at 7.9% and CDs at 3.1% of all music revenue in 2023, up 0.2 and 0.1% from 2022. (Downloads, at least one way to preserve a digital offering in some sort of stone, fell from 3.1% to 2.5%.) The people willing to pay an average of near $30 for an album in 2022 pales in comparison to those who'd rather pay $10 per month and have "all of recorded history" at one's fingertips, appalling payouts be damned.

Of course, it's not nearly "all of recorded history" if you want seemingly niche offerings like The Beatles in mono, the original single edit of George Michael's "I Want Your Sex," or the music that closes the commercially available version of Return of the Jedi, to name just a few examples I could build a whole TED talk around. (There's also, of course, a whole indie class of music makers who've turned their back on Spotify and have, in at least one case, driven at least one tech CEO to near madness.)

That all seems to just be the way it is, if you're trying to buy new or old music on disc, or at least get a sense of deeper history through its files. For as much hay is made about how catalog - that is, music 18 months old or greater - is the preeminent revenue driver of the business, the drive to dig through the archives and, at bare minimum, live up to the promise of freeing bits and bobs from dusty 12"s and forgotten compilations seems to be more sluggish than ever. The box set concept, which could once give long-dead bluesmen Billboard album chart placements and platinum RIAA certifications, has long since retreated to niche territory, and like the medium itself, the digital equivalent is far more inscrutable and ephemeral. (There are, of course still plenty of great labels which put a premium on physically releasing music that major labels have no problem owning but no market-assisted desire to make physically available. For their efforts, they are hit with cost-prohibitive, byzantine licensing and manufacturing conditions that make such work difficult, if not ultimately impossible.)

Obviously, neither I nor anyone else have any sort of salable solutions to these pressing problems. (If I did, I wouldn't be sitting here typing all this!) All I can say is this: buying albums and learning about them, through liner notes and a working knowledge of who played on each one, had a profound effect on how I value art and artists. I cannot be alone in this (physical sales figures aside), and I don't think that this practice was entirely phased out by the digital music revolution; corner-cutting, poor vision, and slow reactions to what people can be offered are the factors we should blame, not the decisions of consumers.

It is my hope that the music business continues to cater to those who feel the same way about the history and creation of art; their enthusiasm and dedication will continue to power the successes of artists. But if the biggest pop stars in the world treat credits like a closely guarded secret - or an album experience becomes an ad hoc scavenger hunt instead of an object to be engaged with - what are listeners supposed to gauge from this? I'll leave that to you to consider while we try to figure out who the hell played on Cowboy Carter, and when it's going to be available physically in full.

While I was writing this, some Cowboy Carter credits made themselves clearer digitally. Thanks to writer Andrew Martone for pointing out that the guitarist on Bey's cover of The Beatles' "Blackbird" is seemingly none other than Paul McCartney himself.