Only Human

Andrea Swensson, Cornbread Harris, and the magic of art and family.

In my life and work, I've always tried to live by a few tenets: do your best, chase your passions, love deeply, and be grateful for what is behind and in front of you. There was no greater affirmation of all those maxims than seeing author Andrea Swensson and legendary musician Jimmy Jam give a talk on Wednesday (October 9) about her latest work: a book on an unheralded legend of Minneapolis' music scene, and how his life's greatest achievement may be reconnecting with the son who followed in his footsteps.

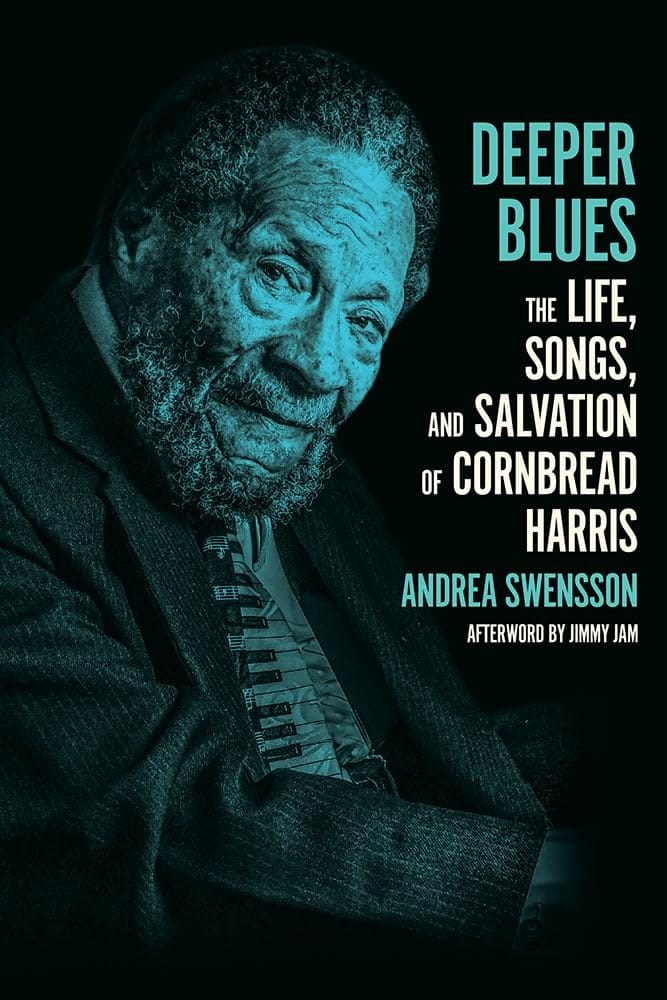

Swensson's new book is Deeper Blues: The Life, Songs and Salvation of Cornbread Harris, a heartfelt biography of James Samuel Harris, Jr., a singer/songwriter/pianist in the Twin Cities. Harris, born in Chicago, was orphaned as a child and came to live in St. Paul with his grandparents. An accomplished musician who gigged relentlessly between shifts at a foundry, his major claim to fame was as the keyboard player of the Augie Garcia Quintet, who in 1955 recorded "Hi Yo Silver," the first rock and roll single recorded in the area. (Harris also sang on the single's B-side, a cover of the blues standard "Goin' to Chicago.") A self-proclaimed "blessed dude" with a youthful twinkle in his 97-year-old eyes, Harris still performs weekly at Palmer's Bar in Minneapolis.

Most clips don't even do Cornbread justice. This new compilation, however, does.

I met Andrea in 2019, when I worked editorial for Legacy Recordings. The label had recently inked a deal with the Prince Estate to distribute his storied catalogue, and I was lucky to attend that year's Celebration at Paisley Park to interview fans about what Prince's music meant to them. Swensson, a Minnesota native, is well-known for her work at brilliant alt-weekly City Pages (where she served as music editor) and Minnesota Public Radio; Prince himself was a fan of her writing in his final years, and her work with the Estate - most notably the Prince Podcast - is some of the most comprehensive deep dives on The Artist ever done. (I'll never forget the feeling that came over me as she pinpointed the front page of The Los Angeles Times that likely inspired the writing of "Sign O' the Times.") I appreciated her kindness as a fellow writer and music geek, and adore her tenacity in finding new and unique ways to research Minnesota's place in music history. (Her first book, 2017's Got to Be Something Here, is a top-down account of what crystallized "the Minneapolis sound.")

This was the video from that Paisley Park trip. I'm very proud of my small contributions to it.

Of course, Cornbread Harris had more than a little to do with that sound beyond even his own work. His son, James Samuel Harris III, was also a pretty accomplished musician in the city - a drummer turned keyboardist who'd joined a funk combo called Flyte Tyme alongside childhood friend and bassist Terry Lewis. Members of that group - Harris, Lewis, keyboardist Monte Moir and drummer Jellybean Johnson - would be reorganized by a young Prince into a side project of his own. With the addition of guitarist Jesse Johnson, singer Morris Day and dancer/percussionist Jerome Benton, The Time recorded several albums for Warner Bros. Records and became a fearsome opener for Prince as his star began to rise. (He played nearly all the instruments on their records, then did everything but sabotage the group when some reviews deemed them the hottest act of the tour.) Harris - nicknamed "Jimmy Jam" by Prince - and Lewis were sacked from the group before the band became his onscreen foil in the 1984 blockbuster Purple Rain, but Jam and Lewis wasted no time in establishing a shingle of their own, writing and producing hits for R&B chart mainstays The S.O.S. Band and Cherrelle before forming a fruitful creative partnership with Janet Jackson on Control (1986) and nearly every album of hers since; they've also written and produced hits for Michael Jackson, Mariah Carey, New Edition, Boyz II Men, Usher and dozens of others. The duo were inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2022, and Jam serves as chairman emeritus for the Recording Academy.

I mean, what a career.

As Deeper Blues reveals, though, Jam and his father had not spoken in decades when Swensson was putting her book together. In the course of writing, though, father and son found their way back to each other, adding a moving meta-narrative to an already impressive story. (Jam writes the book's afterword.) The thoughtful producer, only 15 when his dad left his mother, wanted his father to know that he held no bad blood for how things turned out, instead choosing to value the time they had to get to know each other again. He spoke warmly of believing in things happening for a reason and putting faith in a greater plan, obviously grateful to mend fences and introduce Cornbread to his grandchildren.

It is amazing that Swensson, through her writing, could bring life and light to dark corners like this - it's what many writers dream of doing, even if they won't admit it. Her research showed Cornbread a photo of his mother, who died when he was three, as well as a session Cornbread participated in with musician James Bonner - Jimmy Jam's first time in a recording studio. It's a true testament to the power of history and archives - a drum I will keep beating as long as my arms are able to. And Jam - a musical maverick who could recall old bandmates and venues like it was yesterday, and cited Rick Wakeman as an onstage influence - brought a deeply emotional element to the proceedings. He realized that his father's mannerisms and words to his grandson Max echoed Jam and Max's own relationship. And he passed on wise words to the audience to not let too much time slip by without sharing your feelings to the people that mean something to you, a lesson he said was reinforced by the sudden death of Prince in 2016.

From this lovely night, I will certainly take a renewed affinity for writing and music archivism, as well as a sense of gratitude that I could tell Andrea and Jimmy just what their work means to me. But I also left with a renewed commitment to succeed at my biggest endeavor yet. This year I became a father to twin girls, and the harsh realities of career opportunities for most writers means that I have assumed a lot of parenting responsibilities during the day instead of going to an office to make a regular wage for my family. As I change, feed and dress my daughters and help guide them through new tasks like tasting mashed vegetables and trying to sit upright, I am constantly living in fear that I am doing an astoundingly bad job. Taking care of children is solving a puzzle whose pieces are constantly changing shape or moving away from the nipple of a bottle. To my great shame, I do not always find myself responding the way I want to in the face of these challenges - partly due to my place on the autism spectrum, perhaps, but partly out of fear that I will simply not be up to the task the way I want to. (This is to say nothing of the want - the self-imposed pressure - to do as good a job as my own parents did.)

Hearing Jam talk about his own family - not with a sense of regret at what didn't work, but gratitude at what did - is something that reached a place deep within. The producer was visibly taken aback by a question from the audience about what songs in the Jam/Lewis oeuvre Cornbread enjoyed most. He mentioned there was a plan at one of their few live appearances together to cover The Human League's chart-topping "Human," a lush, tender plea from a man who has done his lover wrong. It is, quite simply, one of my favorite works by the duo - one that speaks deeply to my own anxieties about not being enough. The days may get hard and the blues may get deep, but perhaps there is wisdom in that song to forgive myself, let go and become the best parent I can possibly be - of flesh and blood I'm made, born to make mistakes.

And then, perhaps, I can take a page from the immortal Cornbread Harris, and put the world back together.

May we all have a little Cornbread in our lives.