From the Archive: Sometimes a Fantasy is All You Need

A 2020 essay reflecting on the 40th anniversary of Billy Joel's 'Glass Houses.'

Ohh, he's writing about Billy Joel again? Not really - this is an old piece that ran without a byline on Medium for the 40th anniversary of my favorite Billy Joel album, and the first one I think I ever listened to in full. In 2002, my high school chorus teacher — a profound influence on me — had the select boys' ensemble (we were called the Jades; the school colors were green and white) sing deep cut "Sleeping with the Television On" at the spring concert. The second verse and bridge marked my first ever vocal solo; if I remember correctly, people really liked it. I didn't know I was capable of holding an audience's attention!

This piece originally ran on March 7, 2020, which...hoo boy. About a week later, I woke up at 3 a.m. sweating and unable to control my full-body shivers. Nicole later said she was worried I was going to die. Not great! Unfortunately for the haters, I did not, and am typing this intro for the non-haters with a series of COVID boosters coursing through my veins.

It’s 1980, and Billy Joel is trying to solve a problem.

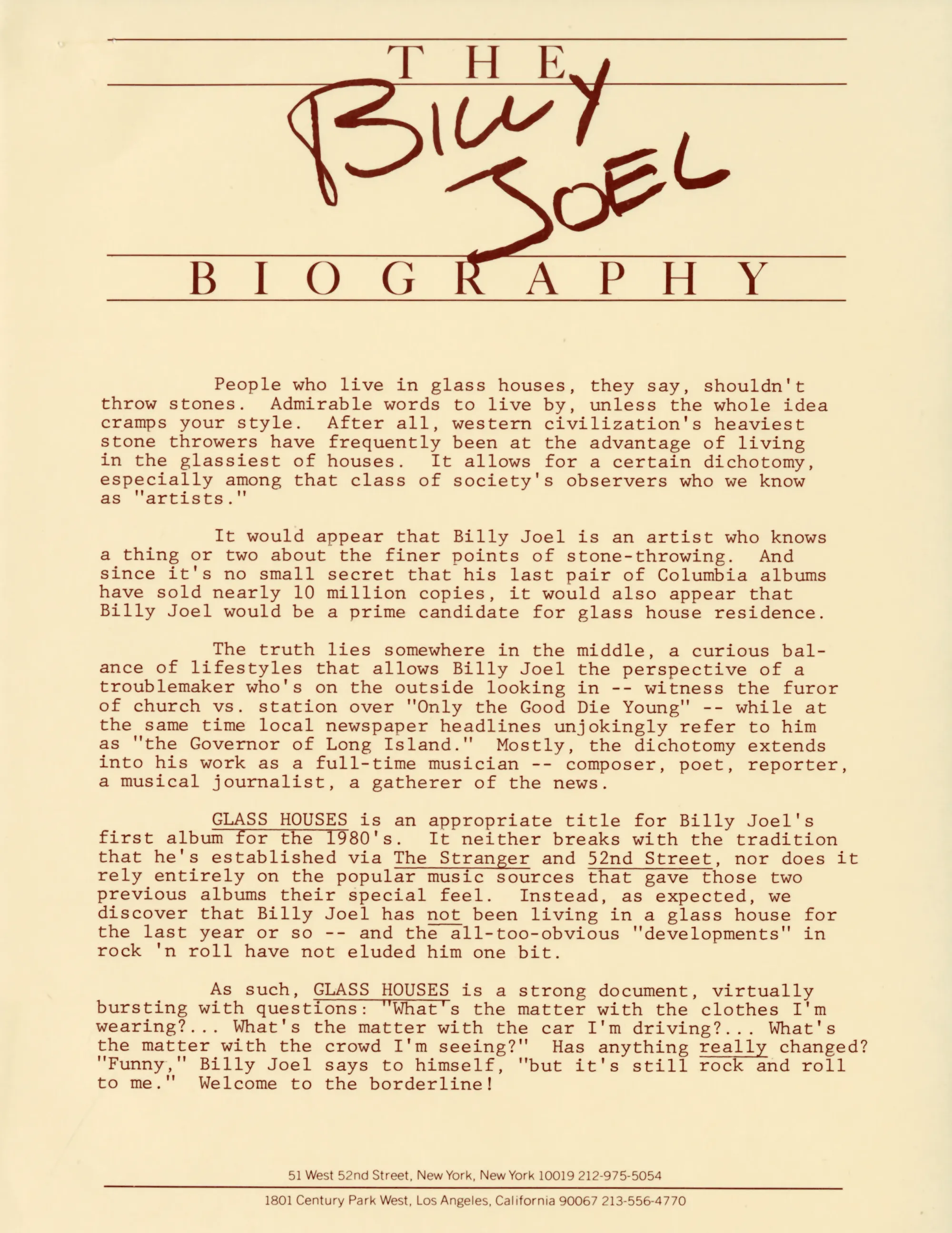

The hardscrabble piano player from Long Island sits in a studio with producer Phil Ramone, who’s collaborated with Joel on blockbuster albums The Stranger (1977) and 52nd Street (1978) as well as the sessions that would make his newest release, Glass Houses. In a discussion that was thankfully recorded and included on Joel’s rarities box set My Lives, Billy and Phil discuss pushing this record in a way that’s different from the others.

“What can I, Billy Joel, do to help promote this thing?” the singer asks, before improvising several ideas at the piano: a jaunty jingle, a sneering piece of punk publicity (“Get the album…soon! Glass Houses! Woo hoo! I don’t care…On CBS Records and Tapes”), even an impersonation of record mogul Don Kirshner on the set of Rock Concert.

Innovative marketing is not always something artists have the answers to, or even care to think about. But this was different — and four decades later, it underlines the stakes of Glass Houses as Billy Joel’s first event record.

Billy Joel chased success for nearly a decade. He’d moved from one end of the country to the other and back again, enduring long nights on countless tours. Record label bigwigs were patient as his first three albums for Columbia Records all just missed the parameters of “commercial acclaim.”

Suddenly, it all clicks. With Ramone’s help, The Stranger captures in the studio the essence of what Billy and his band achieved in concert. Radio jockeys can’t get enough; four singles become Top 40 hits, and another two get solid FM-radio airplay. The romantic “Just The Way You Are” wins two Grammy Awards.

Follow-up 52nd Street proves it wasn’t just a fluke. The crowds get bigger, culminating with four gigs at Madison Square Garden in New York City in late 1978. Another Grammy Award, this time Album of the Year. This is Paul Simon and Stevie Wonder territory. But with that territory comes challenges — primarily the middling reviews Billy earned from mainstream columnists, which he’d often literally rip to shreds onstage. (He’d play nice for a Rolling Stone cover story that year, as well as a fascinating profile for the news program 20/20.)

The record industry’s fortunes were changing, too, thanks in part to the rise of punk and new wave as mutations of the rock ’n’ roll experience. Billy surely noticed, with upstart acts like Elvis Costello, Nick Lowe and Cheap Trick joining him on the Columbia roster. And while he no doubt appreciated the musical adrenaline they offered — not unlike the original British invasion of the ’60s that inspired his musical journey — he couldn’t help but be bemused by it all.

“Everything was being recategorized now, because they needed to define it against something,” Billy later said. “In my neighborhood you didn’t call yourself a punk; other people called you a punk.”

The stage was set: a rock star who’s proven his worth, and a new set of forces on the music market. This could get heavy.

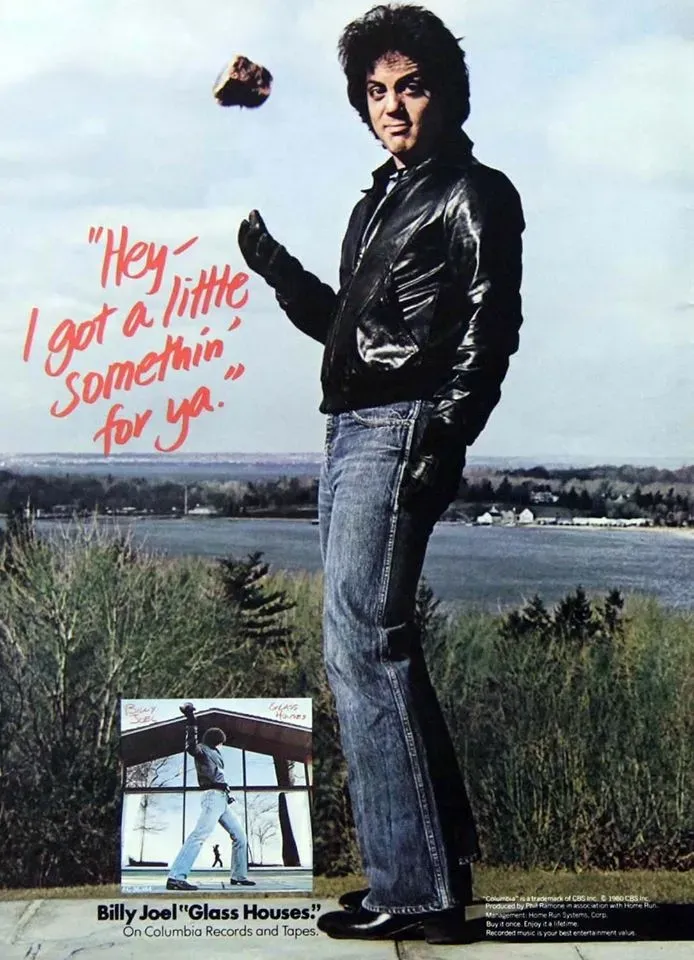

“Hey — I got a little somethin’ for ya,” a leather-jacketed Billy challenged in a print ad for Glass Houses, finally released to the public on March 12, 1980. A rock, tossed upward, is frozen in mid-air next to the singer. On the album sleeve, Billy faces away from the listener, with that rock cocked back at an impressively windowed house on Oyster Bay, Long Island — Billy’s own, it turns out.

This is one of the first two or three Billy Joel singles I think I ever heard. You know how he goes on in interviews now about how he hates his voice? I don't think he's right, but this, "My Life" and "Piano Man" don't necessarily sound like the same guy.

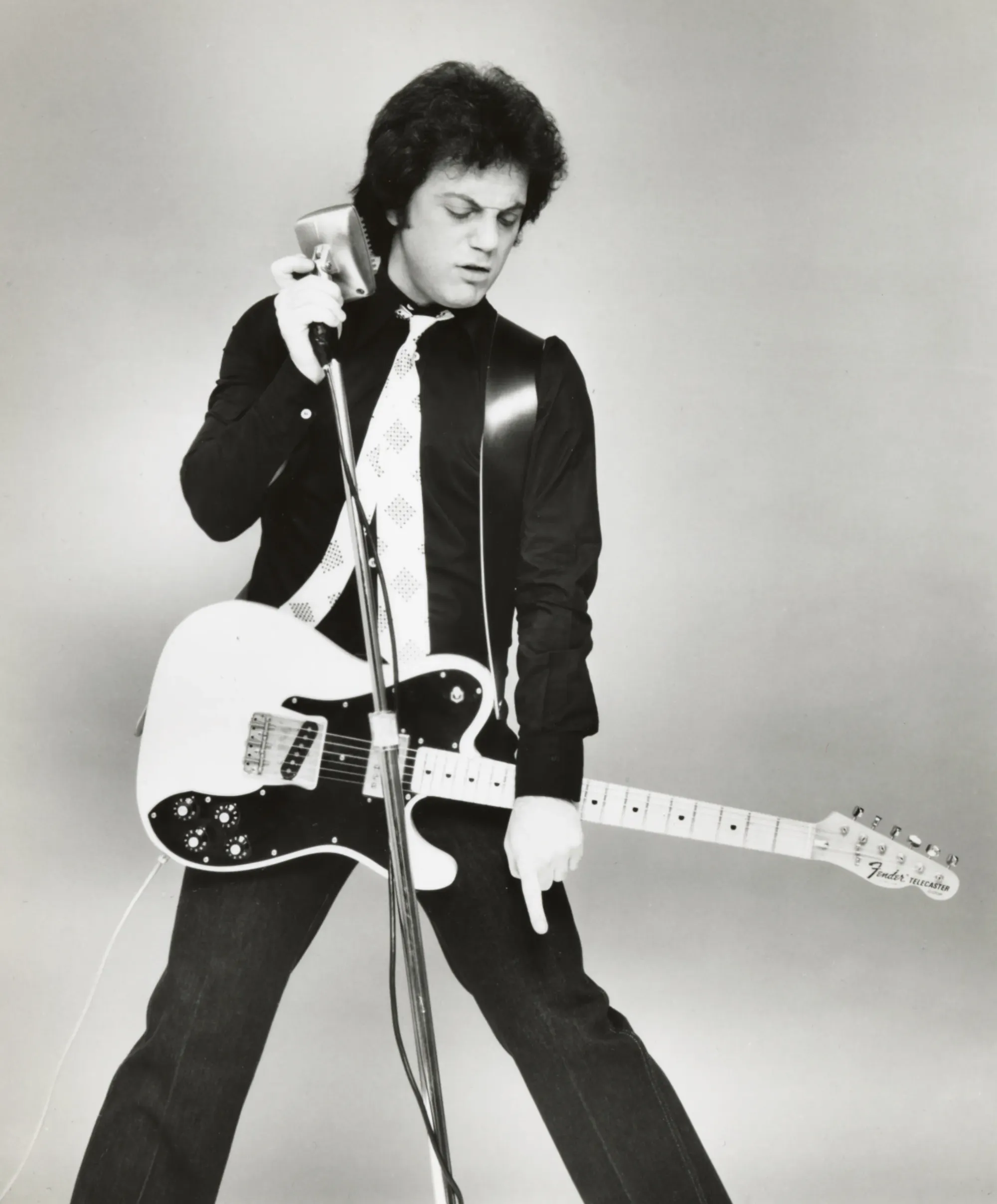

That set-up is paid off the minute the needle hits the groove on Glass Houses: the sound of breaking glass, and the propulsive rock rhythm of “You May Be Right,” the first Top 10 hit from the album. In an unprecedented move, the piano is buried deep into the mix in favor of the rest of the band: the twin axes of new lead guitarist David Brown and returning player Russell Javors, propulsive bassist Doug Stegmeyer, the onslaught of drummer Liberty DeVitto and even the wail of Richie Cannata’s saxophone. Here, Billy plays up the tough-guy style on the album cover to the hilt, growling a catchy tune about a motorcycling cad and the woman that’s putting up with him.

Now, you’ve got ears, and you likely realize that “You May Be Right” is not really a punk song. Over the last 40 years, this idea’s taken hold that Billy was literally “answering” punk or new wave on Glass Houses, and that’s not really true. He flirts with the genre on the album: “All For Leyna,” a song about thirsting for a second night of passion with a wild mystery woman, features staccato electric piano riffs that give off serious post-punk vibes. And killer album cut “Sleeping With The Television On” features an organ solo worthy of Elvis Costello and The Attractions’ This Year’s Model. But Billy’s doing it his way — the only way he knows how.

Adam Levine of Maroon 5 once went up to Billy Joel at a restaurant to have him settle a bet among the band as to what he was yelling before the sax break here. (It's "All right, Rico!") In return, Billy made Adam identify who gave Songs About Jane its title.

That tension over rock styles comes to a head on “It’s Still Rock and Roll To Me,” the album’s second hit single and de facto mission statement. Over a propulsive, more minimal track, Billy questions (and answers) everything about the scene that seems different: clothes, influences and how it’s all drummed up by “the papers” that were pummeling him along the way. “History repeats the old conceits,” Costello would later write, as he sought to expand his horizons beyond the new wave. Billy Joel got it right, and earned his first chart-topping single only a few weeks after Glass Houses became his second LP to top Billboard’s survey.

As an “event” record, Glass Houses also Billy’s chance to tailor his own multifaceted musical approach to the arena audiences he was now entertaining. You can hear that in “You May Be Right” or “Sleeping With The Television On” (which experiment with sound-effects intros) or cherished sleeper hits like “Don’t Ask Me Why” or “Sometimes a Fantasy,” Glass Houses’ third and fourth Top 40 hits.

Someone - maybe Chuck Klosterman - has said Billy's alter ego looks like Joe Piscopo.

The two couldn’t be more different sonically: “Don’t Ask” is a Latin-flavored shuffle powered largely by acoustic guitar, while “Fantasy” is a rocker about some late-night, lascivious phone calls that was accompanied by Billy’s first “concept” music video, a year before MTV hit the airwaves. (Hardcore fans should score “Fantasy” on its original 45, which features an inexplicably longer, unbridled rock outro.) But in concert, then and now, they fill the super-sized crowds with unquestionable vigor.

Glass Houses’ deeper cuts certify Billy’s ongoing status as a musical chameleon. You don’t have to have grown up with the album to appreciate some of the characters Billy creates here, whether it’s the lovable loser of “I Don’t Want To Be Alone” meeting-cute in an ill-fitting suit at the Plaza Hotel’s bar, or the burnout trying to will “Leyna” into calling him back. There might be some misses along the way: “Close To The Borderline” skewers the new rock sound a little too sharply, and Billy himself has all but disowned “C’etait toi (You Were The One),” clowning on his attempt at serenading crowds in French. But then that beautiful, Beatlesesque closer “Through The Long Night,” with its rich vocal harmonies and soothing melody, seals the deal on establishing Billy Joel as a major act for the ‘80s.

Back to Billy and Phil Ramone in that studio, before Glass Houses finds its fans, selling some seven million copies in the United States alone, winning another Grammy Award and setting up another blockbuster tour (chronicled in part on 1981’s solid live album Songs In The Attic). The two are agonizing over how to reach the regional promoters who will help get the album to the heights it reaches.

“Who are we kidding?” Billy asks in a moment of bemused frustration. “Do I have to jive? Be hype and jive? About my new album, Glass Houses? Do I have to keep saying Glass Houses? ‘Glass Houses? This is Billy Joel: Glass Houses.’”

They may not have known what they were working with yet, but 40 years later, we certainly do. Glass Houses is a killer album from a rock icon at the top of his game. Turn it up today — and if you break any windows, please clean after yourself.