The Ghostbusters Guy

They can't stop making these movies. Are people like me to blame - or is it actually my fault?

I. Listen! You Smell Something?

Like so many other moments, it first came through a song.

There were two discs I obediently swapped between on my parents' hi-fi, underused by them but a source for my own personal delight - often by way of cassettes packed with Disney songs or the threadbare megamixes of Jive Bunny.

The first disc was smaller: a 45 RPM single of Huey Lewis and The News' "The Power of Love" that I often replayed by way of the auto restart button on the turntable. The other - bigger, in a black, red and white sleeve, its label bearing purples and pinks of a crested hill and the word "Arista" - was the original soundtrack album to Ghostbusters, a film I'd never seen but was certainly intrigued from what was on the jacket. On the front: a white, cartoon ghost, forlornly gazing as a red circle ringed it and a matching line slashed over it. On the back: a trio of men, looking skyward and pointing some sort of apparatuses above them, attached to backpacks slung over khaki coveralls.

And there it was from the speakers: a chunky LinnDrum beat, synthesizer stabs and a raucous guitar chords; a suave, assured man extolling the virtues of a group known as the Ghostbusters, whose presence was trumpeted by an excited crowd. Then a jaunty piano-and-horns romp about those Ghostbusters and their ability to clean up a town. One song gave way to another before a pair of orchestral instrumentals - one a bouncy, piano-driven theme, the other a torrid love motif with sighing synths - and then, that main song again, this time without lyrics.

As I grooved in the playroom to those 10 songs, I had no idea they would follow me places I didn't expect to go.

II. Proton Charging

I can't remember the order in which the other component parts of Ghostbusters came into my life. I think it went something like this:

- Some kids in my kindergarten class had toy facsimiles of what too many of us know as the "proton pack" (the standard trapping equipment of a Ghostbuster - a kit-bashed, backpack nuclear accelerator with a "neutrona wand" attached to a hose, which would shoot out bursts of colorful energy that would help nab a spirit). One classmate, a towheaded boy named Roy, had his own jumpsuit, perhaps for a Halloween costume, which read on the reverse "Back Off Man, I'm a Ghostbuster."

- I knew enough that Ghostbusters was followed by a Ghostbusters II. I collected Topps trading cards devoted to the film around the same time as other blockbuster fare like Batman Returns or Back to the Future Part II (which I acquired a full set of). That movie had a baby, a rude-looking painting, and that subservient ghost logo replaced by a haughtier model, sticking two fingers out from behind his red paranormal prison.

- There was also The Real Ghostbusters, offering a cartoon version of the characters during afterschool and Saturday morning hours. There were plenty of unmemorable jokes and a closer look at the coolness of ghostbusting. The team's green mascot, Slimer, grinned out from countless juice bottles marketing Hi-C's Ecto Cooler, drunk on the tee-ball field and occasionally at home.

- The 'Busters appeared in an attraction at Universal Studios Florida, a laser-augmented stage show that was a little loud and scary for my early tasts.

- Finally, there was the matter of the actual Ghostbusters film. I believe it was acquired on video by my family through a promotion known as "Camel Cash" - tiny banknote replicas attached to the side of the packs of Camel cigarettes my grandfather smoked. You could redeem them for atrocious cigarette-branded swag or a Columbia House-style list of videotapes, and we opted for the latter.

You gotta love old footage like this on Entertainment Tonight. Sylvester Stallone believes in ghosts!

I need to be very clear about something that may surprise you: while I certainly thrill to watching Ghostbusters if the mood strikes me every few years, I don't know that I would call it a defining work of my youth. Many of the bawdier jokes sailed over my head, and the film certainly lacked the angularity of its cartoon counterpart. It was a recurring favorite, though not as strong as Back to the Future then, or Gremlins a few years later, or E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial ever. I would watch it alone or with friends, and like the soundtrack album, I had no idea what I'd be getting up to with the help of that flick.

III. We Got One

In 2013, I had been consulting for a major music reissue label for more than a year, while still working at Target, a job I'd held since before graduating college four years prior. I lived at home and I felt my goals were out of reach and stalling. I steeped myself in the history and lore of things I liked as a child and sought comfort in them - yet through them, I also found a way to unlock the next chapter of my life.

I'd read that the Licensing Expo, a big convention where brands get together and try to entice each other to collaborate, had a banner from Sony Pictures Entertainment touting some planned 30th anniversary activity for Ghostbusters in 2014. There was even a specially-redesigned logo. Thinking quickly, I realized the label that employed me controlled the rights to the music of the film - was there a marketing opportunity there?

I think the retail price on this was $18.99. Watching this go up on eBay afterward made me seethe. Record Store Day is a weird racket.

Within months, I had drafted my pitch and had my answer: a 10" single of Ray Parker Jr.'s deathless theme (in several different mixes which hadn't been commercially available in several years), pressed on glow-in-the-dark "ecto green" vinyl for Record Store Day, the artificial biannual holiday where major labels press exclusive titles for indie stores to sell and freaks to collect on shelves or flip on eBay. We sent the package to the printers the day Ghostbusters co-writer Harold Ramis passed away and I watched as this idea opened doors for me: when it was released, it was our label's best-seller for Record Store Day, the second-best for the whole company, and the seventh or eighth-best overall. Better yet: by that point I was hired full-time.

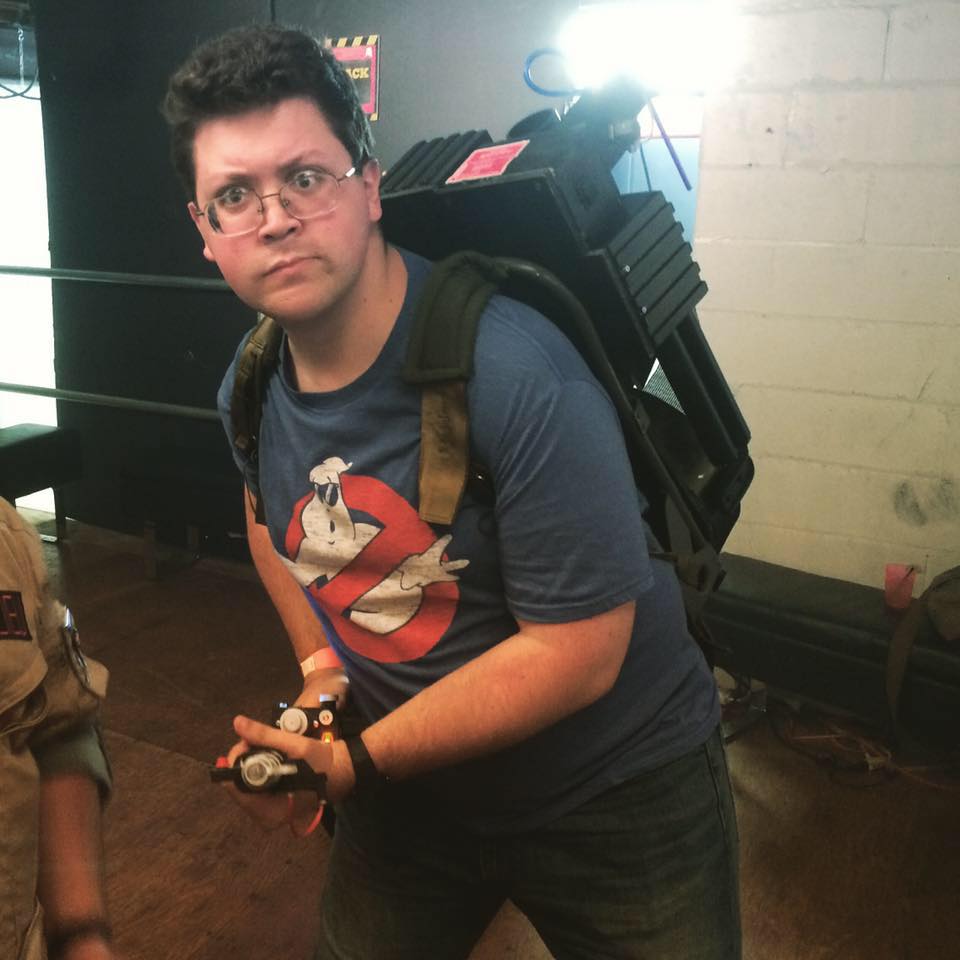

In all the excitement, I'd learned that the 30th anniversary activity was almost certainly a trial balloon for more Ghostbusters films. Before I could consider that, though, I was tasked with helping out with another GB product idea: this time, it would be a white 12" with packaging meant to recall the film's climactic bad guy, a demon in the form of a 100-foot Stay-Puft Marshmallow Man. I'll be honest: I didn't and still don't understand the idea of going back to the Ghostbusters music well. I had other ideas I wanted to actualize! But I played along, and gamely smiled my way through every bit of Ghostbusters news and trivia people sent my way in the years to come. I was happy being thought of, and wasn't going to "um, actually" the attention away by explaining I wasn't quite the Ghostbusters guy that everyone seemed to think I was.

In 2014, we were only getting the first sense of the improbable vinyl revival we're still dealing with now. A critic from The Wall Street Journal writing about said revival put this title on blast; he had a point, but he was kind of a dick about it.

IV. This Man Has No Dick

By the time the Stay-Puft single hit the marketplace, Sony Pictures had already announced plans to make a new Ghostbusters film, unconnected to the characters and events of the first two and starring a quartet of women from Saturday Night Live (the comedy sketch show that gave breakthroughs to original Ghostbusters stars Dan Aykroyd and Bill Murray) and other comedy works (Melissa McCarthy was primarily known for sitcoms and a striking, Oscar-nominated turn in the comedy Bridesmaids; that film's star and co-writer, Kristen Wiig, and director Paul Feig would be part of the new Ghostbusters film). With Ramis dead and Murray seemingly disinterested in reprising the smartass Peter Venkman, this felt like the right choice; also, with so many great women in comedy, it felt like a surefire formula to get folks excited.

This is, of course, not what happened. The 2016 reimagining of Ghostbusters became a flashpoint in a gendered culture war I was only starting to become aware of. In the wake of things like "Gamergate" and the soon-to-be-successful presidential campaign of Donald Trump, a cadre of loud, profoundly insecure and possibly stupid men were holding up a girl version of Ghostbusters as an example of how feminism was "taking things too far" or threatening "traditions" ("traditions" being "a pair of movies where schlubby guys catch ghosts for laughs").

Within a year, a similar pointless controversy would fully embroil another childhood favorite series I enjoyed enough as an adult (Star Wars) - the start of a come-to-Jesus moment that the silly stuff I used as escapism was now a referendum on...something. And all those things were getting rebooted and revived on screens big and small, seemingly at the expense of creating new and original ideas. My ambitions to preserve and contextualize the entertainment of the past was, outside my purview, curdling into a desperate attempt on behalf of pop culture to fit into old pants and sink into the warm grip of old favorites while the new world struggled to be born.

Of course, it's easy to put it all that way now. At the time, I was a lot less articulate about it. How less articulate, you may ask? I am one of the (thankfully) anonymous quotes in this MTV News piece from a Ghostbusters fan event shortly before the reboot was released. If you can guess which one - and honestly, I don't think it's that hard - please, drop a line and let me know.

V. Like the Buzzing of Flies

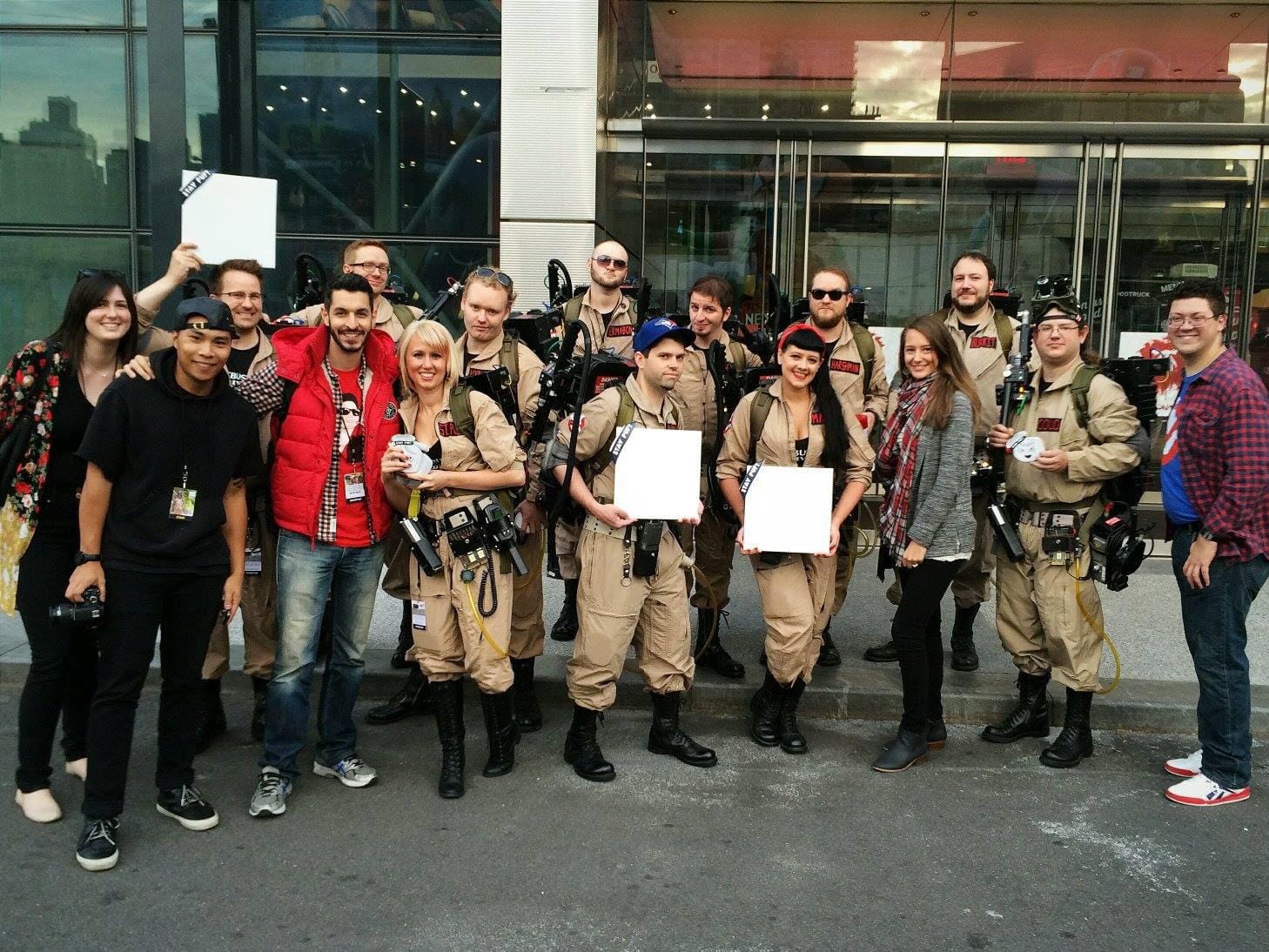

The rebooted Ghostbusters made some money, but not enough to make the dreams of more films a reality, and so it seemed that the franchise would recede into the background. In 2019, the series' 35th anniversary year, I even had two nice interactions with the franchise: the original film's terrific score by Elmer Bernstein was given a wide release for the first time, and I happened to be near TriBeCa's Hook & Ladder No. 8 (the firehouse headquarters used in the film) on the day a group of NYC Ghostbusters were giving a tour for fans.

Later that year, it would become apparent that Ghostbusters was once again my Godfather Part III. Sony announced a sequel to Ghostbusters II that would feature some returning cast and a script co-written by director Jason Reitman, son of Ivan, who directed the first two films plus great comedies like Twins, Kindergarten Cop and Dave. The final product, Ghostbusters: Afterlife, delayed amid the COVID-19 pandemic, was finally released just before Christmas 2021. I've rarely had less fun at a movie.

The premise of Afterlife centers around a single mom who moves her teen kids to an Oklahoma farmhouse vacated by her recently deceased, estranged father. It soon becomes clear that there's something strange in this neighborhood: the father was none other than Egon Spengler, and the family learns (with the help of an underused Paul Rudd and obligatory cameos from the original cast) just what it means to take on the mantle of Ghostbuster.

And what does it mean? Now, it means Amblinesque, Stranger Things-ian wonder, weightless special effects, a desultory climax that shamelessly recycles climactic elements from the original film, and the "presence" of the deceased Ramis as a digitally-recreated ghost who heals family trauma with hugs before departing into the afterlife. The film exists mostly to justify the dewy-eyed paeans of Ghostbusters lore by atrocious nerds who yelled about the 2016 film (which was considerably better) before they dragged their unwitting kids to see this "cool" movie.

The Ghostbusters are treated the way Luke Skywalker is in Disney's Star Wars sequel trilogy: near-mythic figures whose existence and relevance must be uncovered under layers of mystery. That angle makes sense in a vast sci-fi galaxy, perhaps, but does not when the preceding films have the same four guys stop two paranormal 9/11s in America's most populous city, in turn conclusively proving and reaffirming that the afterlife exists. Do you think people would just do YouTube explainers about that? These guys would be Homeland Security by now.

What really made me aghast, when the dust settled, was the idea that a movie like this - which engaged in a lot of fan service (and some sort of family therapy on the younger Reitman's part) instead of actual laugh-out-loud comedy or a significant build on what a Ghostbusters film could be - was considered by the studio to be exactly what fans wanted. Based on the loud reaction by fans online (perhaps done with a degree of self-satisfaction after the 2016 film attempted to change the status quo), they seemed to be correct. Yet, here I was - a perceived super fan who went as far as to create a collectible for other superfans - feeling profoundly guilty. Was Ghostbusters: Afterlife somehow...my fault? Did I help convey the wrong message that what folks like me wanted was a return to the familiar?

VI. In a Spiritual Sense

I write this days after seeing Ghostbusters: Frozen Empire, a sequel to Afterlife and the fifth film in the long-suffering supernatural series. After the profoundly negative experience of the last film, I had joked that the only way I'd go see it is if someone paid me. Ultimately, that is what happened, thanks to an outlet asking for a ranking of the series. Perhaps the bar for endless franchises is in hell - have you seen the last few Marvel movies? - but Frozen Empire was, while slight, far less offensive than expected.

There are profoundly silly callbacks (not only cameos from the New York Public Library ghost from the first film, but the same faculty member from the NYPL); the balance between new and old characters is askew (the Stranger Things kid from the last movie disappears for long stretches of the picture, and there's still a character named "Podcast" with no real character traits other than that); and I still don't understand the shift from teen-to-adult-focused comedy to all-ages action. But the lore was easy to disentangle, and the reverence to the original slightly less mawkish. It is of the same vaguely pleasant middle tier as the 2016 film, though not quite as humorous.

And that's perfectly fine. If entities from the spirit world suffer from unfinished business, I can at long last consider mine finally resolved. Of course these movies are in no way my fault (although I have no problem joking that they might be). I am just one fan of many, filling out no market survey and contributing only a few twenties to a multiplex. Of course I can separate who I am from what I like, appreciating that stuff from the past without letting myself get buried underneath it. (I've worked in the private sector. They expect results.)

I am a Ghostbusters guy, but I do not need to be the Ghostbusters guy. And for that, bustin' makes me feel...acceptance.