Hollywood & Spine Archive: The Moment of Truth

An overview of the novelization to THE KARATE KID, originally published in January 2021.

It is absolutely wild that one of the best legacy sequel/reboots of 21st century Hollywood is a Karate Kid sequel show created by two guys who wrote the Harold & Kumar movies and one guy who wrote the Hot Tub Time Machine movies. This one was fun to go back over; I love when a novelization accidentally anticipates things or themes that appear more explicitly in a sequel. It's maybe the thing that elevates these kinds of books to minor art, for me. (Originally published 1/20/2021)

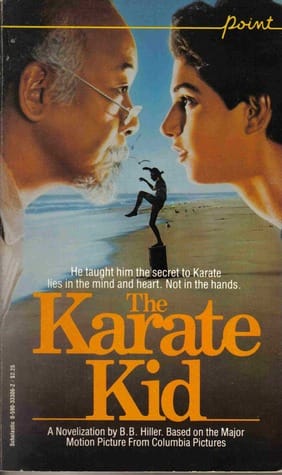

The Karate Kid by B.B. Hiller (based on the screenplay by Robert Mark Kamen) (Point, 1984)

The pitch: A charismatic kid learns the art of self-defense from his mystic (but wisecracking) sensei in one of the decade's biggest sleeper hits.

The author: Barbara B. Hiller left a gig in publishing to pen a long-running series of young reader books (under the name Bonnie Bryant) called The Saddle Club; more than 100 books were published between 1988 and 2001. In the '80s and '90s, she became an accomplished writer of novelizations including Big (co-written with her husband Neil before his death in 1989) and the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles films.

The lowdown: You probably know this, but The Karate Kid is Rocky for kids. Both were based on true-ish events and directed by John G. Avildsen, both featured Italian-American leads in star performances, and both became franchises thanks not only to sequels of varying quality but 21st century reboots that build on the goofiest aspects of those sequels to surprising effect. For Rocky, that reboot is Ryan Coogler's powerful Creed, featuring Michael B. Jordan as the unknown son of the film's original villain Apollo Creed, trained by his aging foe-turned-friend Rocky Balboa.

The Karate Kid's legacy is less prestigious yet still interesting. In 2018, the series Cobra Kai flipped the script on the original film, featuring bad boy Johnny Lawrence (William Zabka) trying to break bad habits and teach martial arts to a new generation of kids, coming into conflict with original protagonist Daniel LaRusso (Ralph Macchio), who defeated and disgraced him back in the '80s. Now in its third season on Netflix, Cobra Kai features a lot of deep-ish thoughts on history repeating itself, toxic masculinity, the generation gap, the mistakes parents try to prevent their kids from making, Gen Z teens trading chops and kicks - and increasingly deep-cut references to mythology laid out by at least three of the four Karate Kid films. (Not bad for a show that's essentially a How I Met Your Mother joke come to life.)

Of course, none of that mythology is in the pages of Hiller's adaptation of The Karate Kid, which comes at an interesting juncture in novelization history. As the age of the blockbuster matured in the '80s, novelizations could do big business - and movies targeted at all audiences could pull double duty when adapted as both novelization and storybook. (William Kotzwinkle, for instance, adapted E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial in both weight classes.) That could have - and maybe should have - been the case for The Karate Kid, published by the Scholastic imprint Point (which, as it turns out, released the novel-length adaptation of Home Alone 2: Lost in New York we covered in a previous volume). Instead, we get a solid 131-page story (longer than the novelization to Rocky!) that, while obviously targeted to young readers, isn't written too cynically.

Unsurprisingly, Hiller's narrative doesn't stray from Daniel's point of view. The details he gleans about characters like his girlfriend Ali Mills (Elizabeth Shue) or apartment handyman-turned-karate instructor Mr. Miyagi (Pat Morita) are filtered through his perspective - there's no deep interior thoughts from the others. That allows Hiller to approach story beats with quiet dignity that intermediate readers might appreciate, like the struggle of dating a girl from a better tax bracket or understanding the pain your Japanese-American sensei is carrying from an internment camp during World War II. (This painful real-life moment in our country's racially-fraught history is described better here than any textbook I recall in school.)

Hiller also carefully balances the sparks that make Mr. Miyagi such a captivating character without trudging into full-on Pacific fetishization. (Cobra Kai stumbles here by omission, featuring exclusively white guys teaching Asian self-defense to a diverse group of teens.) As it likely was in the script - the dialogue here is not terrifically different on the page - Miyagi speaks sagely and cryptically, but it never devolves too far past caricature. (Morita's accent in the film was a put-on, but he knew how to treat the role with respect.)

Some of the dialogue even hints at deeper shades of Miyagi's character that would be fleshed out in the sequels, as in this passage:

Hundreds of blocks and three fish later, Daniel spoke again, without breaking his tempo.

"You ever get into fights when you were a kid?"

"Lots."

"But it wasn't like the problem I have."

"Why not? Fighting all same."

"Well, for one thing, you knew karate."

"Always someone else know more. No different from now."

"You mean there were times when you were scared to fight?"

"Scared all times, Daniel-san. Hate fighting."

"But you like karate."

"So?"

"Karate is fighting. That's why you train: to fight."

"That's what you think, really?"

Was it? Daniel thought a moment.

"No."

"Why train then?" the old man challenged.

"So I won't have to fight."

That's a key theme from The Karate Kid Part II that unwittingly first blooms on the page of this book targeted for pre-teens. You have to appreciate that foreshadowing, whether sourced from Kamen's script or Hiller's adaptation. It certainly makes you feel less silly reading it as an adult.

The cutting room floor: Most of the material presented in the book but not the film is minimal, with one major exception. The book establishes that Daniel's mother's computer job - the reason the pair move across the country - evaporates before she can start, which is why she's working in a Chinese restaurant early in the film instead. The timeline of Daniel and Ali as official couple is a little quicker here - they first kiss at the Halloween dance - and is punctuated by at least one extra scene of Johnny and the Cobra Kai kids bullying Daniel in the lunchroom by placing a piece of pie on his seat.

There's other minor details, too: a brief mention of Miyagi's training dummy, affectionately named Hashimoto, and a subtler redemption arc for Johnny at the end of the story. There is no explicit "sweep the leg" moment here, and it's clear before the fight is done that he respects Daniel's skill. He of course humbly presents Daniel with the trophy at the film's end, which begs the question of what sets the events of Cobra Kai in motion the way it does. But that's for someone else to think about.

By far the biggest change in the novelization is that the story ends where The Karate Kid Part II began - a coda where Cobra Kai leader John Kreese excoriates his students only to be defeated in the parking lot by Miyagi, who makes Kreese anticipate a killing blow but delivers a honk on the nose. That ending was in the original Karate Kid script but punched up and filmed for the sequel (including a verbal lesson from Miyagi about how living with hate in your heart is worse than death) - and it's frankly put to better use there, as it bookends Daniel's fight in Okinawa (which ends the same way - the student becomes the teacher and so on).

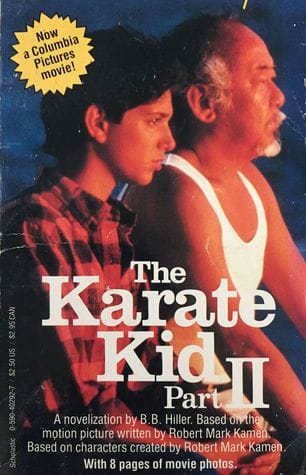

Extra credit: Hiller also wrote novelizations to the less satisfying Karate Kid sequels. Part II is, like its predecessor, a taut but respectful read, published by Point and again featuring the deleted ending from the first film, written by Hiller almost word for word from the first book. Part III, a maniacally boring film, received a rote, 86-page adaptation published by Scholastic that marginally improves on the pacing of the source material by not introducing the villainous Terry Silver as such, and hiding the reintroduction of Kreese until he pops up out of nowhere. (Kids wouldn't go for prose descriptions of a ponytailed dingus discussing unethical business practices while smoking in a hot tub.)

The last word: Hiller's take on The Karate Kid is as lean and no-frills as the satisfying film that inspired it. Like its hero, it possesses enough balance and stamina to score a victory on the page.